Two Neo-Confucian Models of Educating Children: A Comparison between Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming’s Pedagogical Thought

Ⓒ Institute of Confucian Philosophy and Culture, 2020

Abstract

This article seeks to tease out two disparate models of pedagogy in the neo-Confucian tradition. To that end, I focus on the two founding figures of this tradition, namely, Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming, and see how they articulated their ideas on childhood education, which were based upon their conflicting views on children and their innate moral abilities. From Zhu’s point of view, children have incomplete moral capabilities, as they are unable to distinguish between right and wrong, that is, they lack moral awareness and lack the moral will to put any knowledge they do possess in this regard into action. On the contrary, Wang viewed children as being innately endowed with both these faculties, making them legitimate moral actors in their own right. Based upon these diverging stances, their views on child education tend to differ. Zhu argued that the aim of education is to help children develop moral abilities via repeated learning and practice; thus, I will refer to his views as the inculcation model. Whereas Wang held that early education should help children actualize their innate moral faculties; hence, I will call his stance the actualization model.

Keywords:

Infants, children, moral awareness, moral will, education, inculcation, actualizationI. Introduction

The aim of this article is to tease out two disparate models of pedagogy in the neo-Confucian tradition.1 To that end, I focus on the two founding fathers of this tradition, namely, Zhu Xi (1130–1200) and Wang Yangming (1472–1528), who represent the schools of principle (lixue) and mind (xinxue), respectively.2 Indeed, from the Song dynasty (960–1279) onward, as Thomas Lee has pointed out, neo-Confucian scholars placed an emphasis on children and their education as a preliminary, yet critical, step toward individual attainment of moral perfection and, as an extension, social harmony and stability.3 Within this context, Zhu and Wang, among many others, offered new, pioneering, and subversive, but also impactful, discourses on children in terms of their moral development and education.4 Quite naturally, there have been many studies concerning the two thinkers’ pedagogical thoughts written in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese.5 But the problem, in my view, is that these studies are either too descriptive or engaged overly much in value judgments. In the latter case, especially, scholars’ admiring attitudes toward Wang Yangming are particularly notable, as his liberating views on children and childhood resonant well with modern counterparts.6 Being fully aware and wary of this ongoing trend, I will attempt to provide a more structural and systematic comparison between the two figures in light of their pedagogical ideas. On that note, one major strategy that I use in this article is to look into the ways in which they articulated their thoughts on childhood education, building upon their conflicting views on children and their innate moral abilities.

Prior to examining Zhu and Wang’s views on children and their moral foundations, it is worthwhile to first consider what “moral” actually means in neo-Confucian terms; to both Zhu and Wang, the “moral mind” (daoxin) technically meant being other-oriented or altruistic, as represented by the emphasis placed on the “commiserating mind” (ceyin zhi xin). Indeed, this altruistic mind was central to their vision of an “ideal society” (datong shehui), a society that was to be based upon mutual aid and support among, and therefore, the intimate solidarity of, its constituents. Interestingly enough, they even justified this view on a metaphysical level by claiming that the “myriad things in heaven and earth, including oneself, are all connected with each other” (tiandi wanwu yiti)—a view that can be referred to as the neo-Confucian belief in the “unity of all things”—indicating that one ought to regard every being as oneself.7 As a result, all that stands in the way of, and is detrimental to, this unity and thereby brings about social disruptions is to be considered “evil” (e)—especially selfish and material desires. Hence, it was imperative to both Zhu and Wang to eradicate such desires completely, thus preserving one’s moral and altruistic mind throughout one’s lifetime.

It is particularly notable that both Zhu and Wang asserted, following their spiritual teacher Mencius (372–289 BC), that altruistic moral qualities (i.e., “four sprouts,” siduan: commiseration, deference and compliance, a sense of shame and dislike, and a sense of right and wrong) are already inherent in people’s minds; these qualities are commonly referred to as one’s innate “moral nature” (xing) in neo-Confucian terms. However, the ways in which the two thinkers looked upon the “efficacy” of one’s moral nature were rather disparate, as Zhu deemed it to be relatively weak, precarious, and difficult to manifest, whereas Wang affirmed that it was powerful and therefore a reliable moral facilitator in its own right.8 Indeed, these two viewpoints represent the scholars’ diverging paths concerning the extent to which the moral agency of a human being could and ought to be acknowledged. It is in this area that this article will be able to shed new and refreshing light upon their conflicting viewpoints through the lens of their thoughts on children and their moral basis; hopefully in the process, we will see more clearly how and exactly on what points this divergence actually came about and developed between the two figures.

In light of this intent, Eric Schwitzgebel’s thesis is definitely worth mentioning. In his investigation of two ancient Chinese and two early modern European philosophers, namely, Mencius, Xun Zi (310–235 BC), Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), he pointed out that their views on human nature have a direct and decisive bearing upon their views on the proper course of a moral education.9 That is to say, Mencius and Rousseau regarded human nature as essentially good, nice, and morally oriented; as a result, their educational thought revolved mostly around the discovery and development of individuals’ innate moral potential through self-reflection. On the other hand, Xun Zi and Hobbes held rather pessimistic and skeptical positions on human nature itself, viewing individuals as selfish, cunning, and ruthless; as a result, they felt that moral education needed to take a rather harsher form, as in, the indoctrination of moralities from outside the individual, supported with enforcement. Indeed, these two disparate lines of thought can be considered to represent two contrasting models of moral education, based as they are upon diverging stances on individuals’ innate moral bases. In the Chinese intellectual context, in particular, these models resonate very well with Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming’s views on children and their education. Nonetheless, I should argue here that the two thinkers actually offered much more nuanced and sophisticated accounts than their predecessors (Mencius and Xun Zi) regarding children’s education as well as more delicate considerations of their innate moral foundations. By conducting a careful textual analysis, I will illustrate and flesh out how they organized and postulated their pedagogical ideas in such an intricate fashion. Next as Schwitzgebel did, I will place these figures within an “intercultural dialogue” with a view to seeing how these ideas resonate with various pedagogical discourses over time and across cultures albeit quite briefly.

II. Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming’s Views on Children and Their Innate Moral Abilities

1. Zhu Xi and the Infant Mind

Various religious and philosophical traditions have pondered the extent of the innate moral abilities of human beings and what should be done to develop these abilities further. In the Confucian tradition, as we shall discuss in the following pages, the Mencius—an early Confucian classic containing Mencius’ philosophical treatises, dialogues, and catechisms—is particularly notable in this regard. It points out that the “infant mind,” the mind present at birth, already has certain moral capabilities and hence is to be taken seriously in the quest for moral perfection. Indeed, this view is very much in line with Mencius’ major overarching theme, which can be summarized as “human’s innate nature is good” (xingshan), as well as his various discourses on nourishing and developing this innate moral nature in order to become a sage. The following line of the Mencius is worth quoting in this regard:

The great man is he who does not lose his infant mind.10

As Pauline Lee noted (2014, 528–531), there are numerous commentaries on the Mencius—especially by neo-Confucian scholars, such as Zhu Xi, Li Zhi (1527–1602), and Jiao Xun (1763–1820)—that grapple with the line above and offer diverse views as to how to interpret it across different time periods. At least one crucial factor that enabled and facilitated such divergent interpretations is that the concept “infant mind” is mentioned just once in the Mencius, that is, in the quote above, and no contextual clues are offered elsewhere in the text. Therefore, neo-Confucian scholars took up this line not just for the sake of philological rigor but also in attempts to create new and innovative implications and put forth their own agendas. In other words, this hermeneutical problem, based as it is upon a dearth of information, provided ample room for a range of philosophical interpretations in the Chinese commentarial tradition.11

In this sense, the debate between the two giants of early neo-Confucian tradition, Lu Dalin (1046–1092) and Cheng Yi (1033–1107), paved the way for future discourses on the infant mind. Setting aside all the complexities, what was at stake in their discussions was whether the infant mind could serve as a “sufficient condition” for ultimately becoming a sage.12 On that note, Lu perceived of the infant mind as being completely innocent, as in not yet being tainted by any externalities. It is this utter innocence itself, in his terms, that then led to the ability to be fully flexible and responsive toward myriad things and affairs, making it a “sufficient condition” in and of itself. Furthermore, it is in this sense that Lu glossed “not losing” in the line above in a rather literal sense, that is, “to preserve” and “to stick to” the infant mind, with nothing else required. To Cheng, however, such a literal glossing was not very satisfactory and needed to be amended. Although he also acknowledged that the infant mind is perfectly innocent and therefore can serve as a “necessary condition” for attaining sage-hood, he did not view it as a sufficient condition, as he felt it was devoid of the (moral) knowledge necessary for proper thinking and behavior, a deficiency he labelled as “complete ignorance” (yiwu suozhi).13 Accordingly, at this stage, efforts needed to be made in terms of “investigating things and extending knowledge” (gewu zhizhi). In Cheng’s terms, “not losing” does not merely mean “to preserve” but rather points to the need “to extend” or “to develop” the original, incomplete mind.

Zhu Xi, a synthesizer of early neo-Confucian ideas, then embraced and developed the discussions of his predecessors and articulated clearly the nature of the infant mind and what not losing it meant. First and foremost, following Lu, he asserted that the infant mind is an innocent mind, one barely tainted by externalities and therefore largely free of selfish and material desires. He proposed that when one’s infant mind is preserved throughout life, one is not swayed by the selfish impulses arising in one’s mind.14 Zhu Xi also criticized the trend in his own time in great men not keeping their infant minds (“今之大人, 也無那赤子時心.”). In terms of one’s infant mind and its innocence being a crucial moral foundation, Zhu’s comment on the aforesaid line of the Mencius is worth referring to:

The mind of the great man is well versed in myriad changes, and the infant mind is just perfectly innocent without artificiality. However, the reason why the great man becomes the great man is because he is not swayed by any m`aterial enticements and holds the original (mind) of the innocent without artificiality in its own entirety. Therefore, by expanding and filling it out, there is nothing that is not known and that cannot be done, thereby fulfilling its greatness fully.15 (Zhu Xi 1995, 292)

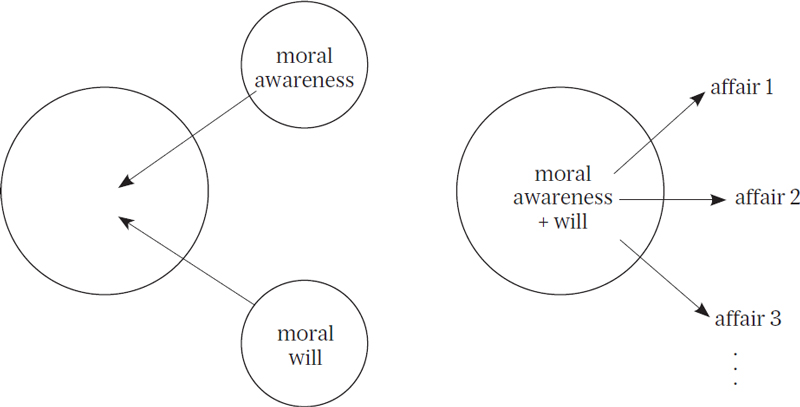

Zhu felt that it was important to keep the infant mind fully intact. At the same time, he argued that it needed to be “extended” and “filled out.” To Pauline Lee (2014, 529) his arguments presented a “conundrum” of sorts, as noted in the following quotation: “Zhu carefully describes his conception of the child-like heart (i.e., infant mind; author) . . . as a fully developed nature but somehow requiring ‘expanding’ and ‘filling out’” (italics added for emphasis). As we shall see below, Zhu has not presented us with a riddle at all on the grounds that he discusses both what is fully developed and lacking in the infant mind. In fact, the latter was more important to Zhu than the former, or innocent mind, in that innocence alone does not guarantee greatness in men. From his point of view, this innate moral virtue is quite limited after all, and he provided two reasons for this view. First, infants are not born with the “moral awareness” (zhijue) necessary for discerning between right and wrong. Although moral behavior is possible, what is at issue here is that even if such behavior is exhibited, there is no knowledge behind it as to whether it is good or bad; put otherwise, actions are taken based on feelings. Zhu Xi also argues that even if infants attain some moral knowledge, they still cannot choose to put this knowledge into action—namely, they have no “moral will” behind their actions. Indeed, these two elements are closely linked in terms of a person’s moral behavior, that is, in order to decide to act morally, one should first be able to distinguish between right and wrong. In order to use one’s moral knowledge, a moral will to do good and refrain from doing bad must be present. It is in this sense that the two ought to go hand in hand since infants have neither property, moral consistency is not possible as Zhu viewed.

In order to conceptualize the nature of the infant mind in Zhu’s terms, it is useful to consider Mark Rowlands’ concept of a “moral subject.”16 Rowlands articulated the term primarily to explicate the moral proclivities of animals. Although animals perform altruistic actions from time to time, such actions are not based upon any moral consciousness (that is, they do not reflect upon their actions, before and after) but rather upon spontaneous emotions. Furthermore, animals do not exhibit a strong will to do good and avoid doing bad, as their instincts, which are powerful and overwhelming, are to be followed, not controlled. Rowlands defines a “moral subject” as a moral actor who naturally behaves morally without a moral awareness of right and wrong and a moral will to do the former and refrain from the latter. Interestingly, this concept can be applied to infants as well; Rowlands does consider small boys to be good examples of moral subjects. Examining Zhu Xi’s “moral subjecthood” in this light, we can witness the infants’ supposed lack of moral awareness and will in the following quote:

The great man has nothing that he does not know and that he is not able to do, and the infant has nothing that he knows and that he is able to do. . . . In general, the infant mind is characterized by not having an awareness, based upon innocence without artificiality, and the great man is characterized by having an awareness on the basis of innocence without artificiality.17 (Zhu Xi 1341[1999])

In brief, having the mind of an infant is a necessary condition for becoming a great man. Indeed, the “calculation” (jijiao)—a term that Zhu uses in a negative sense—done in terms of one’s self interests is the greatest enemy of one’s moral perfection; therefore, protecting the innocence inherent in one’s infant mind could and should be the best remedy for those selfish impulses. However, having an infant mind can never be deemed a sufficient condition because, in order to become a great man, what is lacking must be added faculties for determining what is right and wrong and executing this knowledge at will. Thus, by articulating these two abilities, Zhu Xi developed Cheng’s ideas further through highlighting not just moral awareness but also moral will; the neo-Confucian strand of thought launched by Cheng and Zhu is widely referred to as “Cheng-Zhu learning.” In a letter to Pan Qianzhi (?–?), who perceived of the infant mind as being sufficient for one’s moral accomplishment, Zhu stated: “If the great man only adheres to the infant mind, then there will be an impediment to ‘investigating principles’ (qiongli, moral awareness) and ‘responding to affairs’ (yingshi, moral will)”18 (Zhu Xi 1341[1999], 2757). According to Zhu, the innocence that human beings are endowed with at birth is considerably limited. Thus, he felt that it was imperative to go beyond the innocence of the mind and integrate it with moral knowledge and will, to be acquired via learning and practice, respectively.

2. Wang Yangming and the Innate Knowledge of the Good

Wang Yangming, like Zhu Xi, viewed the infant mind as being free of selfish and material desires and called it the “original mind” (benxin). Interestingly, however, he also asserted that the “infant mind and (the mind of) the great man are identical” (赤子之心與大人同) (Wang 2010, 1349). It is at this point that Zhu Xi and Wang diverge quite radically from each other. The answer as to why and how Wang came to a nearly opposite viewpoint on the infant mind from that of Zhu lies in his concept of the “innate knowledge of the good” (liangzhi, innate knowledge hereafter). The term itself first appears in the Mencius, in which it is defined as one’s primeval moral intuition for discerning right and wrong, that is, a moral consciousness which does not require any thought. The following line from the Mencius—a line that Wang Yangming also quotes in his teachings to pupils—is particularly notable in this regard: “Children carried in the arms all know to love their parents, and (when they are grown a little), they all know to respect their elder brothers.”19 Additionally, this knowledge is coupled with the “innate ability to do good” (liangneng), resulting in moral behavior without acquired learning. Based upon these definitions, Wang often conflated these two concepts with his usage of innate knowledge, resulting in knowledge itself becoming the primordial moral ability to distinguish between good and bad and the inclination to put this knowledge into action—sounding very much like Socrates (470–399 BC), who argued that correct knowledge shows its efficacy in good action.20 Within this context, it is worth considering the following remarks made by Wang:

This innate knowledge is what Mencius meant when he said, “the sense of right and wrong is common to all people.” The sense of right and wrong requires no deliberation, nor does it depend on learning to function. This is why it is called innate knowledge.21

Indeed, Wang considered the moral faculties associated with innate knowledge, that is, moral awareness and will, to be inherent in people’s minds. Wang also expressed this thought as “being born with knowledge and practicing it easily.”22 His notions regarding the infant mind can be regarded as being almost diametrically opposed to those of Zhu Xi. It may be relevant at this point to consider Rowlands’ concept of a “moral agent” along with the term “moral subject.” The latter term reflects being devoid of moral awareness and will whereas the former refers to being equipped with both moral faculties and qualified to act morally. Thus, in Zhu’s (and Rowlands’) terms, infants are moral subjects in need of moral faculties. Wang, on the other hand, would argue that they are already moral agents since they are born with these faculties.

It may be worth noting here that innate knowledge has an enemy in “selfish impulses.”23 Hence, the mind can be construed as an “arena” in which a “spiritual battle” can arise between one’s innate moral faculties and self-oriented desires—especially when the latter grow enough to compete with the former. Therefore, it is essential, in Wang’s view, to exert oneself in eliminating all sorts of selfish impulses while remaining vigilant at all times.24 However, Wang believed it to be equally true that, once selfish desires are removed utterly from one’s mind, innate knowledge can recuperate and operate immediately and properly. Interestingly, in this sense, such efforts are rather unnecessary initially, as the mind in the beginning is completely innocent and free of selfish and material desires. It is at this point that the infant mind can be deemed to be in an ideal condition for innate knowledge to be fully activated, without any hindrances from such desires.

Thus far, it can be seen that Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming diverged a great deal in their notions of the infant mind. Interestingly enough, they also diverged in their ideas concerning a “child’s mind” (tongxin). The term “child’s mind” itself first appears in Chinese textual sources in the chapter covering the 31st year of Duke Xiang’s (Xianggong) reign in the Commentary of Zuo on the Spring and Autumn Annals (Chunqiu zuozhuan), which notes that “Duke Zhao (Zhao Gong) was 19 years old, yet still had a child’s mind. The gentle man was aware that he could not be fully accomplished (by that mind).”25 The same anecdote is also included in the “Biographies of the Dukes of Lu and Zhou” (Lu Zhou gong shijia) in the Records of History (Shiji), in which Fu Qian (?–?), a Confucian scholar of the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD), commented on the tale, as follows: “(Duke Xiang) did not have an aspiration to become an adult and still retained a child’s mind.”26 On the whole, the child’s mind is being delineated here as an immature stage to be overcome in order to reach adulthood. Indeed, Zhu’s view on the child’s mind is very well in line with this viewpoint, as he refers to the child’s mind as needing to be “swept away via learning and practice on a long-term basis, in order not to follow the wrong path.”27 From Wang’s point of view, however, the child’s mind could and ought to be regarded positively given that it was already endowed with, and also offered, the ideal conditions under which innate knowledge could function; hence, Wang (2010, 729, 783, 790) often alludes in his writings (especially in his poetry) to a child’s mind as being equivalent to innate knowledge itself. All in all, the two thinkers diverged quite radically over the issue of the moral basis of infants and children, and these views are reflected fully in their largely disparate pedagogical visions.

III. Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming’s Pedagogical Thought

1. Zhu Xi and the Inculcation Model

Since Zhu Xi’s notions about children and their moral bases are rather pessimistic, he viewed education is essential in helping them to overcome their immature stage and become sages. In this sense, what was crucial to Zhu was to look into and show that the educational system in antiquity was an exemplary model; thus, he notes that, during the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, at the age of 8, children entered “elementary school” (xiaoxue) and received an education in basic moral behavior and principles, such as “sprinkling and sweeping the ground, greeting and replying, and advancing and receding” (灑掃應對進退)—quoting the line from the Analects of Confucius (Lun Yu)—and “loving parents, respecting elders, revering teachers, and being intimate to friends” (愛親敬長隆師親友); the former of which is a materialization of the latter in everyday life (Zhu Xi 2002, 378). At the age of 15, with this education completed, they were advanced to the “grand school” (daxue), which provided an education that included the “search for principles, rectification of the mind, self-cultivation, and governance of the people” (窮理正心修己治人); hence, it focused on philosophical training, moral self-cultivation, and social engagement.28

Perhaps what is particularly notable about Zhu’s account of an elementary education is that the age bracket between 8 and 15 was considered to be a critical period for a person’s moral development, which aligns quite well with the age range indicated in classical Chinese sources on early education. Furthermore, this particular norm seems to have been fully settled by the first and second centuries during the eastern Han dynasty.29 Thus, the Han dynasty work expounding on the proper manners prescribed in the Five Classics (Wu Jing), namely, the Comprehensive Discussions in the White Tiger Hall (Bai Hu Tong), attempts to provide physical and psychological reasons as to why this age frame is important in education:

At the age of eight, children lose their (milk) teeth and their (capacity for) apperception begins; hence, they enter elementary school to study writing and arithmetic. Seven and eight make fifteen, (which represents) the completion of (the interaction of) the yin and the yang. Therefore, (the child) becomes an adolescent, and his understanding becomes clear; he enters the grand school to study classical knowledge.30

According to the quotation above, the age frame between 8 and 15 is important because, psychologically speaking, it is the period in which a child’s consciousness grows based upon his apperception and is established until he becomes an adolescent. Interestingly enough, in the classical education system, elementary schools used this formative (and critical) period for dispensing practical knowledge in the form of basic arithmetic and written characters; the Han-dynasty historian Ban Gu (AD 39–92) noted that knowledge of the Chinese writing system was at the center of children’s education at the time.31 However, it was Zhu who radically changed the contents of elementary education by prioritizing the teaching of moral virtues and habits, as noted above, over practical training; hence, he recommended a moral education that could be conducive to the embodiment of essential moral guidelines at this critical stage of life. In other words, during this period, children should be required to learn what the right thing to do is in all situations and be prepared to put this knowledge into action at all times—i.e., borrowing Rowlands’ ideas again, as moral subjects, they were expected to become moral agents during this stage.

Unfortunately, however, Zhu noted that the moral education for this age group ceased at a certain point, causing people to become self-indulgent and extravagant and creating an atmosphere in which they all became immersed in profit and greed (Zhu Xi 2002, 378). Quite obviously, this is not an accurate historical account but rather a rhetorical strategy to accentuate his new vision for, and the necessity of, a moral education. Furthermore, what we can witness here is a common and serious concern that cut across, and even shaped significantly, the philosophical basis of neo-Confucian scholarship, especially represented by Zhu Xi. That is to say, the “elusiveness of morality” among individuals that could have most likely led to the moral degradation of the world—a concern that Thomas Metzger (1987, 136–161) famously conceptualized as a “sense of predicament.” On that note, Zhu saw a dire need to overcome the moral predicament present in his own time and saw salvation in reviving the lost tradition of elementary education—perhaps more precisely, erecting a new tradition of moral education for children—so that children might once again develop their moral faculties and avoid becoming mired in selfish impulses as adults.

Hence, Zhu, among others, felt the need to write “moral primers” for education and undertook this mission vigorously for most of his scholarly career. One of his most exemplary works in this vein is Indispensable Knowledge for Ignorant Children (Tongmeng xuzhi), a primer that he wrote in 1163. In it, he provided guidelines for routine behavior throughout five chapters: 1) wearing clothes and hats; 2) speaking and walking; 3) sprinkling, cleaning, and bathing; 4) reading and writing characters; and 5) other trivial affairs (衣服冠履, 言語步趨, 灑掃涓潔, 讀書寫文字, 雜細事宜). In the same year, he also authored Quatrains for Teaching the Ignorant (Xunmeng jueju), a compilation 100 stanzas to be taught to children regarding basic moral virtues and principles selected from the Four Books (Sishu), a compendium of essential Confucian texts (Analects of Confucius, Mencius, Great Learning, and Doctrine of the Mean), which was compiled, edited, and commented upon by Zhu himself. Most importantly (and ultimately), these endeavors culminated in the publication of Elementary Learning (Xiaoxue), a textbook for children’s education that Zhu’s pupil Liu Zicheng (?–?) compiled under Zhu’s tutelage in 1187. This work contains a massive collection of excerpts from various texts—including the classics, histories, and literary anthologies of three dynasties up into the Song—regarding etiquette for daily life, proverbs for self-cultivation, and historical portrayals of loyal subjects and filial sons.32 On the whole, Zhu’s primers were geared toward the instruction of children in moral behavior and principles.

The real problem, however, was that children were unable to study these primers on their own because, in Zhu’s mind, they were simply moral subject without the knowledge of good and bad and lacking in moral will. As a result, how could they motivate themselves to learn about such things in the first place? Zhu felt that the best way to overcome this issue was to use “repeated injection,” so to speak, via external enforcement (i.e., families, schools, and so forth). In other words, adults had no choice but to imbue children with moral awareness and will via repetition, as in: 1) exposing children to didactic words, and 2) having them practice moral behavior, as put forth and clearly exemplified in the primers, in a repetitive fashion. Only when this training was completed at age 15 were they to study Daxue (Great Learning) in full to grasp the fundamental moral principles behind it. In a nutshell, the education of children, to Zhu, consisted of “drilling” children so that they could come to fully embody moral behavior and principles. Thus, his views of education can be compared to domesticating animals. I think it is a process that embeds certain values and patterns of behavior in animals via repeated discipline as Cheng Yi once alluded to in his analogy between education and rearing calves and young swine. Here, it is worth reminding ourselves of Rowlands’ characterization of animals and young boys alike as “moral subjects.”33 Hence, when Zhu compiled Jinsilu (Reflections on Things at Hand), a guidebook on all of neo-Confucian thought, he quoted Cheng to emphasize the significance of repeated injection in childhood education, as follows:

In the method of great learning, the first thing is to prevent evil before it starts. When a person is young, he is not the master of his own knowledge or thought. Proverbs and sound doctrines should be spread in front (of him) every day. Although he does not understand, let their fragrance and sound surround him so his ears and mind can be filled with them. In time he will become so accustomed to them that it will be as if he had them originally. Even if someone tries to delude him with other ideas, they will not be able to penetrate him. But if there has been no prevention, when he grows older, selfish ideas and unbalanced desires will grow within, and arguments from many mouths will drill in from the outside, and it will be impossible for him to be pure and perfect. (Chu Hsi and Lu 1967, 260–261).34

As mentioned earlier, children are considered to be completely innocent in neo-Confucian terms. Thus, it is not necessary to worry about children, as they are free of any selfish desires at this stage. What Cheng was concerned about then is that they can be easily and readily tainted by such desires in the future, as they have no faculty for distinguishing between right and wrong and therefore cannot protect themselves from any possible moral threats. Hence, what was at stake for Cheng in terms of childhood education was “preventing” children from being subjected to any worldly thoughts that could possibly lead to their self-oriented desires; in other words, education should be equivalent to equipping children with “moral armor,” so to speak. Nonetheless, because children were to start “from scratch,” as in without any moral knowledge, Cheng’s prescriptive measure was rather harsh and rigorous in that it was designed to force children to hear, and be exposed to, didactic words at all times and on a regular basis. The idea was to embed these words so firmly in their minds that it would be as if they were originally present there. Thus, these didactic words were meant to provide guidance as to what was right and what was wrong in any situation. This viewpoint was eventually reflected in Zhu’s pedagogical stance as well. Hence, their joint educational aim at this stage of childhood was to make sure that moral awareness was fully imprinted in children’s minds through repeated indoctrination. Zhu expresses this viewpoint in his preface to Elementary Learning, as follows:

At all costs, impelling people to memorize and practice them (that is, moral principles and behavior, respectively) in their youth is geared toward the growth of their practice along with their wisdom, so their edification is to be accomplished along with (the maturation of) the mind.35 (Zhu Xi 2002, 378)

As above, Zhu suggests that two cultivational methods, memorization and practice, be used for the moral perfection of children. Indeed, the significance placed on memorization in childhood education, which appears to have been already fleshed out by Cheng Yi based on Zhu’s quote above, indicates that children were to be exposed to the moral guidelines found in Elementary Learning and other primers repeatedly, to the point of internalizing these doctrines fully. In other words, this method was geared toward the infusion of moral awareness in children’s minds. Nonetheless, Zhu Xi did not feel that moral awareness alone was sufficient and thus also pointed out that moral will, as noted earlier, was a crucial component that needed to be appended to Cheng’s ideas concerning children’s moral perfection. Hence, this element was to be reflected in their moral education as well—an element that was to be developed through relentless practice until correct behaviors were entrenched to the point of becoming habits. In this vein, Zhu’s use of the character “xi” (習) in “to practice” deserves further analysis here. He actually glossed the character in his commentary on the Analects of Confucius with “birds flapping their wings frequently in order to fly” (習鳥數飛也).36 In that sense, he seems to have been following the glossing of the character “xi” in Shuowen jiezi 說文解字 (Explaining Graphs and Analyzing Characters), in which it is actually referred to as “frequently flapping their wings” 數飛.37 Interestingly, in the same account, the character “xi” also references little birds, as in “birds with white feathers” (羽+白), thus implying that repeated practice should be demanded at an early stage in life. In addition, he duplicated Cheng Yi’s glossing of the character in “to practice is to practice repeatedly” (習重習也) (Zhu Xi 1995, 58). Thus, he continually highlighted the importance of repetitive cultivation and enforced this iterative practice in a strict fashion in order to enhance children’s moral will to follow the correct behavior for given situations. All in all, the key to Zhu’s pedagogical thought is the repeated indoctrination of moral principles and behavior, which I encapsulate by describing it as the “inculcation model.”

2. Wang Yangming and the Actualization Model

Wang Yangming argues that the minds of infants and children are innately endowed with the ability to distinguish between right and wrong and the inclination to act on this knowledge. In this sense, all human beings are moral agents from the time they are born, all with the potential to be fully independent moral actors in their own right. For this reason, Mou Zongsan (1909–1995) viewed Wang’s ethical thought as being predicated on the notion of “moral autonomy,” an affirmation of people’s inherent moral capabilities and lack of necessity for any external authority.38 Indeed, Wang’s radical assertation rested on his concept of innate knowledge, which embodied both moral awareness and will. It is why his pedagogical thought cannot and should not be in agreement with Zhu Xi’s insistence on the rigorous inculcation of these moral faculties into children. Instead, he meant to liberate them from such restrictions and nurture them rather freely. The following quotation signals this intent:

Generally speaking, it is the nature of young boys to love to play and dislike restrictions. Like plants beginning to sprout, if they are allowed to grow freely, they will develop smoothly. If twisted and interfered with, they will wither and decline. In teaching young boys today, we must make them lean toward rousing themselves so that they will be happy and cheerful at heart and then nothing can check their development. As in the case of plants, if nourished by timely rain and spring wind, they will all sprout, shoot up, and flourish, and will grow naturally in sunlight and develop under the moon. If ice and frost strip them of leaves, their spirit of life will be dissipated, and they will gradually dry up.39

Definitely, Wang felt that restricting children was not a good way to help them be moral. When he used the term “restricting,” he was referring to the prevalent educational practices of his day that were focused on, among other methods, imposing rote memorization and recitation upon children, as well as curtailing their manners and behavior in a strict fashion (Wang 2017, sec. 195). In his analogy between the educational process and growing plants, therefore, such practices are deemed equivalent to the ice and frost that are detrimental to, and further kill off, a plant’s (a child’s) vitality. Instead, children, with their innate knowledge, should be educated in such a manner as to bring out this knowledge—in which they should delight—with nothing else required for their moral development. If this arousal fails to occur under a coercive atmosphere, then their original moral abilities will be crushed, never to be restored again.

In fact, the arousing of oneself toward innate knowledge, as emphasized by Wang above, is closely associated with his doctrine of “extending and realizing innate knowledge” (zhi liangzhi), a doctrine that he proclaimed to be one of his final teachings in later life.40 Here, “extending” and “realizing” innate knowledge refers to tapping one’s innate moral “potential.” In other words, moral awareness and will, both components of knowledge, form the foundation of one’s moral actions. And yet, the existence of the former does not guarantee the latter; accordingly, “effort” is required to convert those faculties into concrete moral action.41 For this reason, Wang emphasizes that: “(Innate) knowledge is the direction of action, and action the effort of knowledge.”42 Interestingly, though Wang says little about how exactly this effort is to be put forth. The reason for this apparent omission is most likely that Wang could and should have believed that such an ability was inherent and natural; thus, everyone could make the effort no matter what the situation.43 Wang argues that even the sages—those who are naturally, and in temperament, free of selfish and material desires—need to exert themselves to extend and realize their innate moral potential into proper action. The following conversation between Wang and his disciple is worth quoting in that regard:

I asked, “It is by nature that the sage is born with knowledge and can practice it naturally and easily. What is the need of any effort?

The teacher (Wang Yangming) said, “Knowledge and action are effort. . . . Innate knowledge is by nature refined and clear. In the wish to be filial toward parents, those who are born with knowledge and can practice it easily only follow innate knowledge and sincerely and earnestly practice filial piety to the utmost. . . . Although the sage is born with knowledge and can practice (this knowledge) easily, he is not overly self-confident and is willing to learn through hard work and practicing (this learning) with effort.44

In the above quotation, it is not very convincing, at least to me, that Wang has answered his disciple’s question fully and legitimately. However, it is clear that he felt that it is was important to “act” upon innate knowledge properly and in accordance with the given situation. In this sense, quoting Wang’s own metaphor, innate knowledge can be likened to an oar steering and propelling a boat in different weather conditions and currents as it is extended and realized.45 Thus, Wang is directing us to exert ourselves to bring our innate knowledge to fruition by using it to propel proper actions in our everyday lives. For instance, Wang often mentions that when one is with one’s parents, one should extend and realize this innate knowledge to the point of serving one’s parents with sincerity. Additionally, one should do the same to follow one’s brothers and serve one’s rulers to the best of one’s ability.46 In a nutshell, innate knowledge should be converted into timely and adequate moral actions requiring different moral virtues, such as filial piety, brotherly love, and loyalty. Furthermore, one needs to take these actions to the fullest extent possible. Simply put, it is imperative to Wang that actions be taken in daily settings based on innate knowledge of right and good.

It is important, then, to highlight the significance of “affairs” (shi) in Wang’s thought. Indeed, over the course of people’s lives, they will inevitably perceive and experience varied affairs. In order to conceptualize what is meant by this phrase, the German philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) coined the term “Lebenswelt” (literally, lifeworld), that is, the state of affairs through which our world is experienced and lived—a concept that is perfectly aligned with Wang’s notions of the world.47 Undoubtedly, one’s Lebenswelt expands naturally from birth as new and unfamiliar situations are experienced over time. Indeed, it is this human development that requires the activation and realization of one’s innate knowledge to deal with these affairs to the best of one’s ability. Quoting Wang: “Here is our innate knowledge today. We should extend it (and fill it out) to the utmost according to what we know today. As our innate knowledge is further developed tomorrow, we should extend it to the utmost according to what we know then.”48 In this respect, it is worth returning to the earlier line that Wang quoted from the Mencius, namely, infants and children all “know to love their parents and to respect their brothers.” Generally speaking, this quote appears to represent the spectrum of affairs experienced by infants and children. However, one’s Lebenswelt eventually expands beyond parents and siblings and exposes one to unfamiliar affairs and situations. It is then one’s duty to keep up with these varied affairs while keeping ones’ innate knowledge fully targeted and manifested toward them at all times.

To Wang, the role of education is to help children extend and realize their innate knowledge in the various situations encountered in their everyday lives. Wang viewed such assistance is especially required for children because the wide range of affairs taking place around them demands that they manifest their innate moral faculties to navigate many rather foreign and unfamiliar situations. Wang clearly illustrates his pedagogical vision in the quotation below from his most detailed account on education (“school regulations,” jiaoyue):

Every day, early in the morning, after the pupils have assembled and bowed, the teacher should ask all of them one by one whether at home they have been negligent and lacked sincerity and earnestness in their desire to love their parents and respect their elders, whether they have overlooked or failed to carry out any detail in caring for their parents in the summer or winter, whether when walking along the streets their movements and etiquette have been disorderly or careless, and whether in all their words, acts, and thoughts they have been deceitful or depraved and not loyal, faithful, sincere, and respectful. All boys must answer honestly. If they have made any mistake, they should correct it. If not, they should devote themselves to greater effort. In addition, the teacher should at all times, and in connection with anything that may occur, use special means to explain and teach them.49 (Wang 2017, sec. 196)

Zhu Xi felt that it was the moral primers on which he worked himself that were important in terms of inculcating moral guidelines for thoughts and actions into children. From Wang’s point of view, however, these primers were not necessary, as these guidelines were already present in children’s minds. All that was required was for children’s “innate guidelines,” so to speak, to work through various situations from daily life while receiving additional help via “dialogues” with their teachers. During these dialogues, the teachers were to make enquiries as to how their students “acted” when confronted with various affairs and, upon receiving honest answers, determine whether their actions were appropriate or not.50 At first glance, this process might come across as teachers offering “guidance” to children concerning proper actions, but it actually demands a more sophisticated interpretation. Using Wang’s logic, the necessary guidance is already inherent in children’s minds; so all teachers need do is arouse that inner guidance by reaffirming and rearticulating it through verbal means. As a result, the mission of teachers can be better characterized as consulting with, or counseling, their students regarding their attitudes and actions, thereby helping them to extend and realize their innate guidance, or “hit the mark,” in any given situation. Wang called this process “examining the virtues” (kaode), that is, teachers and students together checking whether or not the students’ moral virtues, such as filial piety, brotherly love, loyalty, trustworthiness, propriety, righteousness, and a sense of shame (孝弟忠信禮義廉恥), are displayed fully in different situations.51 Moreover, it is through this process that children should see themselves developing into full-fledged moral actors. Given the significance of extending and realizing innate knowledge in Wang’s pedagogical thought, I have labeled his discourse on childhood education the “actualization model.”

IV. Conclusion

In this article, I have examined the two disparate models of childhood education posited by Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming based upon their diverging notions of children’s moral foundations. Although they shared a common goal for children to be equipped with and hold full sway over moral awareness and will, and both saw education to be a crucial stepping-stone in this process, they parted with each other quite radically in terms of the specific methods to be used in this education. Their differences in this regard hinge on their opposing views on the innate moral abilities of children. From Zhu’s point of view, children were devoid of both moral awareness and will, indicating a long road toward the attainment of sage-hood. On the other hand, Wang viewed children as being inherently endowed with both faculties, making them sages in their own right. For Zhu, then, what was first needed was to inculcate the missing moral awareness and will into children by having them listen to moral and didactic discourses and practice morally correct behavior repeatedly. For Wang, however, this process was unnecessary as children were already are in full possession of these faculties. Instead, he claimed that early education should consist of no more than helping children actualize their innate moral faculties when confronted with various affairs in their everyday lives (Figure 1).

In concluding, I would like to argue that the debate on children’s education between Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming is not just limited to the neo-Confucian tradition but can also be looked upon at a universal level. In order to expand the argument, examining these figures using a wider comparative perspective is of paramount importance. Clearly, this mission demands a considerable amount of work and research, and my aim here is rather humble and modest in that it merely alludes to, or hints at, how resonant Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming’s pedagogical theories are with discourses taking place in other cultures and at different times. In this sense, the following two discussions, one from continental European pedagogy and the other from American psychotherapy, are particularly noteworthy:

- 1. Pedagogically speaking, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) is famous for criticizing Rousseau’s rather “romantic” educational thoughts—as noted in his magnum opus Emile, or on education (f. Émile, ou De l'éducation)—which were based upon his utter trust in the innate nature (or natural state) of the child and highlighted self-love, care, and reflection as being crucial for their education. Although partly influenced by Rousseau’s “naturalistic” pedagogical vision, Kant argued that children need to grow up to become legitimate moral thinkers and actors in their social settings.52 To that end, it is worth noting that Kant was particularly conscious and wary of the “moral weakness” of human beings; therefore, he championed a rigorous course of education to enhance their moral judgment and will, thus envisioning a “civilizing,” and ultimately “moralizing,” process. Hence, it was imperative for teachers, in Kant’s terms, to offer moral maxims and instructions (especially using historical didactic examples) and impose constraints and discipline on their behavior, so that they could fully internalize, and act upon, moral norms in the different forms of the “categorical imperative” and not be easily swayed by their natural emotions and passions, thus realizing his vision of “enlightenment pedagogy.” However, the well-known Dutch educationalist Martinus Langeveld (1905–1989), among many others, found Kant’s pedagogical thought to be too “one-directional” (for this purpose, he quoted the following lines from Kant’s Lectures on Pedagogy [g. über Pädagogik]: “The human being can only become human through education. He is nothing except what education makes of him.”) and argued for taking children’s innate abilities more seriously.53 He went on to note that children are actually inclined to explore and understand unknown situations and problems with which they are confronted in their Lebenswelt—and further to convert this understanding into proper responses to those situations. Thus, the role of pedagogues, in Langeveld’s terms, is to help students to develop and manifest these inclinations into concrete and practical action through their rich visions for acting and thinking, a process which he refers to as “phenomenological pedagogy.”54

- 2. The second example is the debate within twentieth-century psychotherapy between the “directive” and “non-directive” approaches in counseling. From the early twentieth century onward, directive counseling was seen as the generic, and most dominant, approach to psychotherapy and counseling—as posited by the American psychologist Edmund Williamson (1900–1979), who played a leading role in the emergence of the counseling field. Indeed, this counseling method places heavy emphasis on counselors using their professional knowledge to intervene actively and directly in clients’ problems. In other words, counselors are to analyze their client’s problems as objectively as possible using the scientific, or statistical, method and offer proper guidance and instructions that clients can and should follow to remedy their problems.55 However, Carl Rogers (1902–1987), Williamson’s contemporary and an American psychotherapist, proclaimed that this therapeutic method was rather unhealthy for clients (including children)—due to its top-down and “undemocratic” characteristics—and proposed instead that “non-directive counseling” be used. In non-directive counseling, counselors are to have strong faith in their clients’ innate abilities to resolve their own issues and play a “minimalist” role in helping them to “display” and “actualize” these abilities.56 Rogers was later criticized significantly for his utter optimism regarding the innate power of his clients; much as Wang Yangming was accused of anointing all people “sages.” However, even to this day, his non-directive viewpoint is taken seriously as having laid the groundwork for contemporary psychotherapeutic practices.

Very roughly speaking, it seems that these three sets of pedagogical (and psychotherapeutic) theories can be divided into two different camps; Zhu Xi, Kant, and Williamson all in one camp for placing an emphasis on the direct and active intervention of teachers (or counselors) based upon their skeptical and pessimistic viewpoints on students’ (or clients’) innate qualities, while Wang Yangming, Langeveld, and Rogers in the other camp for attempting to reconfigure the role of the former in accordance with the escalating status of the latter. Overall, the distinction made between the inculcation and actualization models appears to be quite valid. Indeed, by focusing more on connectivity than differences within each group of thinkers, I was able to examine the overarching logical patterns or “grammar,” so to speak, that cut across, and were equally relevant to, their pedagogical reasoning at a macroscopic level—all the while using Eric Schwitzgebel’s approach of tying views on people’s innate abilities to pedagogical theories. On that note, I rather disagree with Pauline Lee’s thesis regarding the discovery of “native (or specifically Confucian)” theories on children and childhood within the Chinese philosophical tradition; to that end, she also makes comparisons, while often tackling Freudian and “Enlightenment” frameworks on childhood, especially with the American-German psychologist Erik Erikson’s (1902–1994) theory on children’s development, which is based upon his well-known “identity crisis” thesis (P. Lee 2014, 536–539). That being said, if we widen our perspectives and bring in more diverse pedagogical models, whether or not—or to what extent—those theories can really be deemed unique and indigenous could easily and readily be put into question. Of course, it does not necessarily mean that I intend to disregard or downplay any extant major or minor differences between these (and any other) pedagogical models. Rather, I hope that future studies will tackle this deficiency with nuanced, detailed, and sophisticated accounts that illustrate and flesh out, more carefully and thoroughly, the comparisons between the aforesaid theories (and beyond). Suffice it to say that, for the moment, it is enough to have discovered some common threads through the rather cursory and sketchy descriptions above with which to guide the comparative and conversational study of various pedagogical models across time and cultures.

先生曰, 知, 行二字, 即是功夫. . . . 良知原是精精明明的. 如欲孝親, 生知安行的, 只是依此真知落實盡孝而已. . . . 聖人雖是生知安行, 然其心不敢自是肯做困知, 勉行的功夫. See Wang (2017, sec. 291).

Wang wrote this piece at age 47 (1518) when he subdued the rebellions (mostly by bandits) in Southern Gan and thereafter encouraged people in the province to establish schools (xueshe) and devote themselves to educating children.

References

-

Bol, Peter K. 2008. Neo-Confucianism in History, 197–217. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/book61523]

- Ch’oe, Chaemok. 2006. Higashiajia yōmei gaku no tenkai 東アジア陽明學の展開 (The Unfolding of Yangming Learning in East Asia), 23–25. Tokyo: Perikasha.

- Ching, Julia. 1976. To Acquire Wisdom: The Way of Wang Yangming, 104–124. NYC: Columbia University Press.

- Chu Hsi [Zhu Xi], and Tsu-ch’ien Lu, eds. 1967. “Jiaoxue” 敎學 (The Way to Teach). In Reflections on Things at Hand: The Neo-Confucian Anthology. Translated by Wing-tsit Chan, 260–261. NYC: Columbia University Press.

- de Bary, William Theodore. 1981. Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy and the Learning of the Mind-And-Heart. NYC: Columbia University Press.

-

Gardner, Daniel K. 1998. “Confucian Commentary and Chinese Intellectual History.” Journal of Asian Studies 57: 397–422.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2658830]

- Gu, Ban. 1952. Po Hu T’ung: The Comprehensive Discussions in the White Tiger Hall, vol. 2. Translated by Tjan Tjoe Som. Leiden: Brill.

- Guo, Zhai 郭齊, and Yin Bo 尹波, eds. 1996. Zhu Xi ji 朱熹集 (Literary Collection of Zhu Xi), 4474. Chengdu: Sichuan jiaoyu chubanshe.

-

Hsiung, Ping-chen. 2012. “In the Beginning: Searching for Childhood in Chinese History and Philosophy,” in Confucianism, Chinese History and Society, edited by Wong Sin Kiong. Singapore: World Scientific.

[https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814374484_0009]

-

Israel, George L. 2016. “The Renaissance of Wang Yangming Studies in the People’s Republic of China.” Philosophy East and West 66: 1001–1019.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2016.0057]

- Ivanhoe, Philip J. 2002. Ethics in the Confucian Tradition: The Thought of Mencius and Wang Yangming. Cambridge: Hackett Publishing.

- Ivanhoe, Philip J. 2017. Oneness: East Asian Conceptions of Virtue, Happiness, and How We Are All Connected, 13–103. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kant, Immanuel. 2011. “Lectures on Pedagogy.” In Anthropology, History, and Education. Translated by Robert B. Louden, 434–485. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-

Kelleher, M. Theresa. 1989. “Back to Basics: Chu Hsi’s Elementary Learning (Hsiao-hsueh).” In Neo-Confucian Education: The Formative Stage, edited by William Theodore de Bary and John W. Chaffee, 219–251. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520318670-010]

- Lai, Chen. 2006. Youwu zhi jing: Wang Yangming zhexue de jingshen (The Boundary of Being and Non-Being: The Spirit of Wang Yangming’s Philosophy). Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe.

-

Langeveld, Martinus Jan. 1983. “Reflections on Phenomenology and Pedagogy,” translated by Max van Manen. In Phenomenology+Pedagogy, vol. 1.

[https://doi.org/10.29173/pandp14870]

-

Lee, Pauline. 2014. “Two Confucian Theories on Children and Childhood: Commentaries on the Analects and the Mengzi.” Dao: A Journal of Comparative Philosophy 13: 528–531.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11712-014-9401-2]

- Lee, Thomas H. C. 1984. “The Discovery of Childhood: Children Education in Sung China (960–1279).” In Kultur: Begriff und wort in China und Japan, edited by Sigrid Paul. Berlin: Deitrich Reimer Verlag.

-

Levering, Bas. 2012. “Martinus Jan Langeveld: Modern Education of Everyday Upbringing.” In Education and the Kyoto School of Philosophy: Pedagogy for Human Transformation, edited by Paul Standish and Naoko Saito, 135–145. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4047-1_10]

- Li, Jingde 黎請德, ed. 1341 (1999). Zhuzi yulei 朱子語類 (Classified Conversations of Master Zhu). Beijing: Zhonghua shuji.

- Mencius. 2010. The Works of Mencius. Translated by James Legge, 322. Seattle: Pacific Publishing Company.

- Metzger, Thomas A. 1987. Escape from Predicament: Neo-Confucianism and China’s Evolving Political Culture, 136–161. NYC: Columbia University Press.

- Mou, Zongsan. 1968. Xinti yu xingti 心體與性體 (Substance of Mind And Substance Of Human Nature), vol. 1, 115–137. Taipei: Zhengzhong shuju.

-

Pangle, Lorraine S. 2014. Virtue Is knowledge: The Moral Foundations of Socratic Political Philosophy, 81–130. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226136684.003.0004]

-

Ramaekers, Stefan. 2017. “Langeveld, Martinus J. (1905–1989).” In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, edited by Michael A. Peters, 1235–1236. Singapore: Springer.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-588-4_203]

- Rogers, Carl R. 1980. A Way of Being: The Founder of the Human Potential Movement Looks Back on a Distinguished Career, 113–263. NYC: Houghton Mifflin Company.

-

Roth, Klas, and Chris W. Surprenant, eds. 2012. Kant and Education: Interpretations and Commentary, 107–151. NYC: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203348086]

-

Rowlands, Mark. 2012. Can Animals Be Moral? NYC: Oxford University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199842001.001.0001]

- Salvatori, Mariolina R., ed. 2003. Pedagogy: Disturbing History, 1820–1930. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Schwitzgebel, Eric. 2007. “Human Nature and Moral Education in Mencius, Xunzi, Hobbes, and Rousseau.” History of Philosophy Quarterly 24: 147.

- Shu, Jingnan. 2017. Wang Yangming nianpu changbian 王陽明年譜長編 (A Long Edition of the Chronology of Wang Yangming), 1108–1111. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.

- Smith, David W. 2013. Husserl, 327–339. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Wang, Yangming. 1983. Wangyangming chuanxilu xiangzhu jiping 王陽明傳習錄詳註集評 (Detailed Annotations and Collected Comments on the Instructions for Practical Living), edited by Wing Tsit-chan 陳榮捷. Taipei: Taiwan xuesheng shuju.

- Wang, Yangming. 2010. Wang Yangming quanji: xin bianben 王陽明全集: 新編本 (A Complete Anthology of Wang Yangming). New ed. Edited by Wu Guang 吳光 et al. Hangzhou: Zhejiang guji chubanshe.

- Wang, Yangming. 2017. Instructions for Practical Living and Other Neo-Confucian Writings. Translated by Wing-tsit Chan. London: FB & C.

- Williamson, Edmund. 1965. Vocational Counseling: Some Historical, Philosophical, and Theoretical Perspectives, 110–211. NYC: McGraw-Hill.

- Xu Shen. 1988. Shouwen jiezi 說文解字 (Explaining Graphs and Analyzing Characters), 148. Taiwan: Shijie shuju.

- Yi, Cheng, and Cheng Hao. 2006. “Yu Lu Dalin lun zhong shu” 與呂大臨論中書 (Letters to Lu Dalin through the Discussion). In Vol 9 of Erchengji 二程集 (Literary Collection of the Two Cheng Brothers). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

- Zhu Xi. 1995. Sishu zhangju jizhu 四書章句集注 (The Commentaries on Zhu Xi’s Parsing of, and Commentary on, the Four Books). Shanghai: Shanghai gujin chubanshe.

- Zhu Xi. 2002. “Xiaoxue yuanxu” 小學原序 (A Preface to Elementary Learning). In Zhuzi quanshu 朱子全書 (A Complete Collection of the Writings of Master Zhu), 378. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshu.

- Zhu Xi. ed. 1992. Ercheng yishu 二程遺書 (The Posthumous Records of the Two Cheng Brothers: Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe.