A Criminological Test of Confucian Family Centrism

© Institute of Confucian Philosophy and Culture, 2021

Abstract

The present study analyzes how Confucian family centrism influences criminality within society. In many ways Confucian culture is Chinese culture, so to understand Confucian crime control practices is to understand China. Material relating to crime prevention was filtered out of prominent Confucian texts, and it was then evaluated and tested using NLSY97 data. The data was obtained from the first wave of responses produced by the NLSY97, with a sample of 4,599 males from the United States between the ages of 12-16. Confucian family centrism was linked to lower levels of delinquency and other negative life outcomes in males. Results showed that boy’s delinquency, behavioral/emotional problems, and stealing were significantly lower with authoritative fathering, a style of parenting associated with Confucian family centrism. Furthermore, higher levels of parental monitoring exhibited by the residential father produced significantly lower levels of delinquency, substance abuse, behavioral/emotional problems, and stealing among boys; higher levels of parental monitoring are strongly Confucian family centric in nature. These findings hold even after controlling for numerous variables including ethnicity, age, the mothers parenting style, family income, and so on. This test of Confucian family centrism adds support to Confucian parenting theory and Confucian criminological theory.

Keywords:

Confucianism, crime, parenting, family, NLSY97, Confucian family centrismConfucius (551-479 BCE), arguably the greatest and most profound of all Chinese sages, was deeply involved in crime prevention and crime related issues. Confucius was the Minister of Crime in his home state of Lu, and evidence indicates that his ability to reduce crime and control the citizenry was effective (Confucius 1971 [1893]). His self-control, social control, and deviance reduction philosophy, when instituted within his home state in his capacity as the Minister of Crime, was apparently so effective (the state of Lu was so safe, productive, harmonious, and crime free) that he became a threat to neighboring states, which, through a conspiracy among the leaders of these neighboring states, ultimately precipitated his removal from power. Crime related issues were at the forefront of much of Confucius’, Mencius’, and Xunzi’s (the three great pre-Qin Confucians whose philosophy constitutes the foundation of Confucianism) professional work, and this significantly shaped their overall philosophy.1

This is an examination of the Confucian theory of family centrism on crime prevention. Confucius, Mencius, and Xunzi, who were active from the 6th to the 3rd centuries BCE, are pertinent to criminal justice issues as they were regular consultants to feudal state leadership on issues of regulating, correcting, punishing, and controlling people. Thus, theory on the causes and remedies for crime were widely covered within their philosophical texts. Confucian family centrism is tested by NLSY97 data.

Studies have been produced on how extant legal systems relate to pre-Qin Confucian philosophy (Cheng 1948; Kim 2015; Lee and Lai 1978), and Braithwaite (2003, 2015) and Liu (2007) touched on Confucian theory in their work involving restorative justice, but no analysis or tests of Confucian family centrism from a criminological perspective have been conducted.

I. Confucian Family Centrism

The Confucians believed that our natural disposition is that of gradations of love. We first and most intensely love those closest to us, our immediate family members, and we expand our love out from there at different levels depending on familial and proximal relatedness. Our love is strongest with our immediate family, slightly less strong with our extended family (aunts, uncles, cousins, distant cousins, and so on), then, as we move away from our family, our love diminishes more and more as we move to our distant relatives, to the community, the county, the state, and so on. Smith likened this love to a series of concentric circles, writing, “As for the increase of this heart-mind that is hsin, it expands in concentric circles that begin with oneself and spreads from there to include successively one’s family, one’s face-to-face community, one’s nation, and finally all humanity” (Smith 1991, 182; as quoted in Lan 2015). Bell and Metz observed that Confucianism extends its relational spectrum to explicitly include foreigners and even the animal kingdom, writing:

The web of caring obligations that binds family members is more demanding than that binding citizens (or perhaps legal residents), the web of such obligations that bind citizens is more demanding than that binding foreigners, the web binding humans is more demanding than that binding nonhuman forms of life, and so on. (Bell and Metz 2011, 88)

The position that the family is the center of authentic love is instrumental to the Confucian worldview, and it is considered paramount in crime prevention. Crime prevention takes place within the family as that is where the intense love and affection resides.

A. The Family

The family unit and family cohesion are central to Confucian remedies for crime. The family is the root of behavior acquisition and the nucleus of society. The type and quality of affection exhibited between family members, and the moral lessons and ritual based guidance transmitted from parents to children represent a major factor in determining the children’s future behavior—particularly in the self-control and morality required to suppress deviant behavior. This affection and guidance are to begin immediately after the child is born and continue unabated in an intense manner throughout childhood. Confucius (1971 [1893]) explains the initial phase of the parenting procedure, “It is not until a child is three years old that it is allowed to leave the arms of its parents” (17.21, 328). This quote is emblematic of the intense dedication and supervision expected of parents throughout their children’s development. The pre-Qin Confucian book of ritual known as The Book of Rites or the Li Ki, which conveys the Confucian family centric worldview, describes how parents have the capacity to influence children, “He should be (as if he were) hearing (his parents) when there is no voice from them, and as seeing them when they are not actually there” (Legge 2016: Qu Li 1.11), and it explains how the son should behave toward his father:

In serving his father, (a son) should conceal (his faults), and not openly or strongly remonstrate with him about them; should in every possible way wait on and nourish him, without being tied to definite rules; should serve him laboriously till his death, and then complete the mourning for him for three years. (Legge 2016: Tan Gong 1.67)

Other more general examples of the extreme dedication to the family expected within Confucianism include Confucius’s observation that:

Now filial piety is the root of (all) virtue, and (the stem) out of which grows (all moral) teaching. . . . When we have established our character by the practice of the (filial) course, so as to make our name famous in the future ages, and thereby glorify our parents:—this is the end of filial piety. It commences with the service of parents; it proceeds to the service of the ruler; it is completed by the establishment of the character. (Misc. Confucian School 1879, pt. 1, 465)

B. The Center of All Things

The family and the family as a unit is valued over all else within pre-Qin Confucian philosophy—even to the extent that it supersedes the law and the state. If the father engages in serious criminal behavior, it is expected, according to both Confucius and Mencius, that the son cover-up for the crimes of the father so that the father’s crimes will not be detected by the authorities or that the father will not be apprehended by the authorities. The same holds true if the son is the criminal, wherein the father is expected to cover for the crimes of the son. Confucius (2008) explains:

The Duke of She told Master Kong [Confucius]: “In my locality there is a certain paragon, for when his father stole a sheep, he, the son, bore witness against him.’ Master Kong said: ‘In my locality those who are upright are different from this. Fathers cover up for their sons and sons cover up for their fathers. Uprightness is to be found in this.” (13.18, 51)

Mencius took this notion further, asserting that not only should a son aid in the flight of his criminal father, but that 1) he should cover for his father even if his father commits serious offenses such as murder, and 2) he should be prepared to ruin or greatly diminish his own life—even going so far as having a king abdicate his thrown to save his criminal father—in the process. Mencius (2004) explains the acceptable behavior of an emperor when the emperor’s father commits a serious criminal offence:

T’ao Ying asked [Mencius], “When Shun was Emperor and Kao Yao was the judge, if the Blind Man [Emperor Shun’s father] killed a man, what was to be done?”

“The only thing to do was to apprehend him.”

“In that case, would Shun [the Emperor] not try to stop it?”

“How could Shun [the Emperor] stop it? Kao Yao [the judge] had authority for what he did.”

“Then what would Shun have done?”

[Mencius]: “Shun looked upon casting aside the Empire as no more than discarding a worn shoe. He would have secretly carried the old man on his back and fled to the edge of the Sea and lived there happily, never giving a thought to the Empire.” (VII. A. 35, 153)

In this case, many will consider the behavior of the son or the father, when covering for the other, to be immoral and troubling, but it must be conveyed that if any behavior is expected to disrupt the unity of the family or dissolve the family it is to be rejected in favor of any action that will ensure the continuation of a united and functional family.2

The importance of the family in teaching and promoting virtuous behavior is paramount in the Confucian tradition. The lessons and examples passed down from parents to children, mainly through ritual, moral instruction, and forms of academic learning, were considered by the Confucians to be the root from which moral behavior springs. Confucius (2008) said this about the role of the family in the prevention of civil disorder:

Few indeed are those who are naturally filial towards their parents and dutiful towards their elder brothers but are fond of opposing their superiors; and it never happens that those who do not like opposing their superiors are fond of creating civil disorder. The gentleman concerns himself with the root; and if the root is firmly planted, the Way grows. Filial piety and fraternal duty—surely, they are the roots of humaneness. (1.2, p. 3)

The root of humaneness is the family, particularly in the actions of the parents in the upbringing of children and in the filial piety reciprocated to the parents later in life. Who we become as human beings is a direct result of the type of family environment from which we emerge. Those who acquire the proper moral lessons and behavioral patterns will likely go on to be dutiful towards their parents, family, community, superiors, country, and ruler. Those children who engage in productive behaviors and interactions with their parents will engage in a continuation of these behaviors and interactions with other inhabitants within their communities and within society—which generates a harmonious society generally unburdened by civil misconduct and deviance.

C. Family Centrism and Authentic Love

Family centric gradations of love exhibited within society is, per the Confucians, evidence that the family is of most importance in the development and wellbeing of people. When authentic love and affection is strong, as it often is within an immediate family (relative to the love and affection shared between nonrelatives or strangers), people take it upon themselves to authentically nurture and provide for each other.

Among family members there is a greater unconscious drive to show love and sacrifice for one another when compared to other nonrelated members of society. Mencius (2004) explains:

Presumably there must have been cases in ancient times of people not burying their parents. When the parents died, they were thrown in the gullies. Then one day the sons passed the place and there lay the bodies, eaten by foxes and sucked by flies. A sweat broke out on their brows, and they could not bear to look. The sweating was not put on for others to see. It was as outward expression of their innermost heart. They went home for baskets and spades. If it was truly right for them to bury the remains of their parents, then it must also be right for all dutiful sons and benevolent men to do likewise. (III. A. 5, 63)

This sweating and instinctive turning away from the gruesome scene of parental decomposition represents a deep affection for close relatives. As a correlate, Mencius (2004) was once asked if people love one another equally, regardless of blood affiliation, and he responded, “Does Yi Tzu [the questioner] truly believe that a man loves his brother’s son no more than his neighbor’s newborn baby?” (III.A.5, 62-63). Mencius is conveying that a man will love a close blood relative more than a nonrelated person in the community. It is from this love that a dedication to the well-being of one’s children is generated. It is from this dedication to the children that, through moral and ritual based instruction, the children develop self-control and a working morality.

D. Education within the Family

Within the Confucian tradition, parents are expected to instruct their children on matters pertaining to morality, ritual, and general knowledge. This education is to be long-term, rigorous, and constant. The prominent pre-Qin Confucian text The Great Learning explains parental expectations, “What is meant by ‘In order rightly to govern the State, it is necessary first to regulate the family,’ is this:—It is not possible for one to teach others, while he cannot teach his own family” (Confucius [1893] 1971: The Great Learning IX.I, 370). Though this advice is directed toward the ruling classes in this instance, it speaks to two important elements within the family-education equation. The first, though it may seem rather obvious, is that parents must instruct their children. The second is that once parents have mastered the task of instruction within the home, they can then be considered capable of providing advice for others. Stated differently, if one is incapable, through poor instruction, incompetence, or other circumstances, of producing morally sound and competent children, their ability to instruct others and provide advice for community members may be seriously questioned.

Of high importance are the rituals that are expected to be taught and practiced within the family. It is within this ritual based framework of social behavior and social hierarchies that children are expected to learn and practice many forms of self-control, filial piety, and hierarchy recognition, all of which is anticipated to result in greater personal control and diminished expressions of deviance and criminality.

Lastly, and importantly, Confucius, in his capacity as Minister of Crime, was confronted with a domestic dispute between a father and son. Confucius was prompted by a superior to execute the son for his being unfilial towards his father. Confucius refused this request, claiming the father had failed to properly educate his son on filial piety. From this episode, the importance Confucius placed on a father educating his son is clear. This event, interpreted and described by James Legge, transpired thusly:

A father having brought some charge against his son, Confucius kept them both in prison for three months, without making any difference in favour of the father, and then wished to dismiss them both. The head of the Chi was dissatisfied, and said, ‘You are playing with me, Sir Minister of Crime. Formerly you told me that in a State or a family filial duty was the first thing to be insisted on. What hinders you now from putting to death this unfilial son as an example to all the people?’ Confucius with a sigh replied, ‘When superiors fail in their duty, and yet go to put their inferiors to death, it is not right. This father has not taught his son to be filial [emphasis added];—to listen to his charge would be to slay the guiltless. (Confucius[1893] 1971, 74)

Per Confucius, if parents fail to control and regulate their children through ritual, moral instruction, and in other scholastic education, their children will have a greater likelihood of exhibiting criminal behavior.

E. The Role of the Father

Of all the relationships that exist within the social hierarchy, the Confucians believed that the father-son relationship is the most vital. When this relationship is destroyed or severely disrupted—because of father absenteeism, the father lacking in morals or cultivation, and so on—the future behavioral outlook of the son is not expected to be promising. Because of the father’s failure to cultivate himself or understand his role within the upbringing of his children, the son will be unable to acquire the moral framework—a moral framework that is derived from instruction in ritual and morality—necessary to prevent deviance and wrongdoing. Thus, the father’s position within the Confucian family system is vitally important and a major determining factor in the future behavior (criminal or otherwise) of his children.

It is, the Confucians argued, the responsibility of the father to teach his children and regulate his family. If the father is immoral, uneducated, and uncultivated, his ability to produce a vibrant and productive family will be greatly diminished. Mencius illustrates this point, “If you do not practice the Way yourself, you will not have your way even with your own wife and children” (Mencius 2004, VII. B.9). Confucius spoke of the importance of the father within family regulation when he said:

It is said in the Book of Poetry, “Happy union with wife and children, is like the music of lutes and harps. When there is concord among brethren, the harmony is delightful and enduring. Thus, may you regulate your family, and enjoy the pleasures of your wife and children.” (Legge 1893: Doctrine of the Mean XV.V.2, 396)

Society comes secondary to, and functions as a product of, the operation and quality of the family system. Mencius explains the hierarchal nature of Confucian society in these general terms, “There is a common expression, “The Empire, the state, the family.” The Empire has its basis in the state, the state in the family, and the family in one’s own self” (Mencius IV.A.5, 79)

II. Evolutionary and Biological Explanations for Confucian Family Centrism

My aim in this section is to show that people have a natural predilection to engage in Confucian family centrism because it produces the greatest success for their offspring, thus making it more palatable for people to accept and implement. To make this argument, kin selection theory and the Cinderella effect are employed and analyzed within the context of inherited parenting behaviors and the future behavior and success of children. This section argues that people have inherited dispositions that favor ourselves and our own kin, and rather than try to overcome these ingrained dispositions, which may be difficult or nearly impossible on a large scale as it runs in opposition to the successful evolutionary mechanisms that have put us here today, we should work to better understand them, work to refine them to create a more just society, and promote those elements that are conducive to a flourishing society.

A. Kin Selection

The inherent need to provide greater love to close family members, as espoused in Confucian family centrism, can be tied to evolutionary theory and Darwinian natural selection, particularly as it relates to an adaptive strategy within natural selection known as kin selection. Kin selection is an evolutionarily theory developed by William Hamilton and John Maynard Smith, and later advanced and popularized by Robert Trivers in conjunction with his work on reciprocal altruism. Kin selection is a form of natural selection operating at the level of the family, or genetically related groups of organisms, instead of explicitly at the level of the individual. It is a method for gene replication or gene propagation utilized by some species, and it explains why people have evolved to behave altruistically to those who are genetically joined with them.

Genetic material maintains its continued existence through two main strategies, individual mating and kin selection. The first strategy, individual mating, is the survival and reproduction of the gene directly from within the body in which it is contained. This is accomplished when one gains access to a mate, and, through reproductive processes with one’s mate, directly propagates one’s genes into the next generation. It is the case of one person individually spreading one’s own genes through reproduction with another individual. The second method, kin selection, is the survival and propagation of one’s genetic information by enhancing the reproductive success of those who carry similar genetic information (genetically related family members or kin). This is typically achieved by one member of a family sacrificing some or all genetic fitness (reproductive and survival capacity) to improve the genetic fitness of another member of the family or several other members of the family.

This type of sacrificial or fitness reducing behavior is acceptable from a gene-level perspective because in the game of gene propagation all that matters is that the gene is passed to the next generation, it does not matter which body the gene is in—and genetically related family members carry significant amounts of each other’s genetic information. Those family members closely related to you likely carry greater amounts of your genes, while those more distant in family relation likely carry fewer of your genes, and nonrelatives carry fewer still. To put this in a proportional perspective, one-half of your genes are shared with your children, yet only around one-eighth of your genes mirror those of your cousin, thus, the odds that you would be willing to sacrifice fitness for your children (or be altruistic toward your children), as opposed to your cousin, are greater.

At the end of the day, as long as one’s genes continue on into the future, then, from a genetic standpoint, success has been achieved. One body can sacrifice itself or lose a significant amount of fitness for another body, and this is perfectly acceptable from a gene-level perspective if that other body contains a substantial portion of the same genetic information as the sacrificial body. As Gottschalk writes, “If a gene in my body can find a way to assist any copies of itself that reside in another body, that gene will spread” (2002, 268-269). From a kin selection perspective, we can understand why parents stick around to raise their offspring: it is simply one genetic entity working to ensure the fitness of another genetic entity that shares its genes. One can see evidence of kin selection by examining the cellular relationships operating within a single body. Gottschalk explains:

The gene’s-eye view can play hell with our common-sense ideas about an individual and a social group. But, it also allows you to see the “altruistic” sacrifice that your white blood cells make on behalf of all the other cells that are you. . . . Your body is like an ant colony wherein every “ant” (i.e. cell) is perfectly related to every other “ant.” Thus, every cell in you submerges its interests to the good of the group. . . . The idea is to see through the organism to the replicating entities themselves. Even the altruism that occurs between organisms that are not genetically identical, is working in the interests of the genes that are shared. It is still the copies of genes that are benefiting. (Gottschalk 2002, 276)

Kin selection, through the general processes of natural selection, has effectively engrained within humans a predisposition to altruistically provide greater material goods for, and engage in a greater emotional connection with, those who share the same genetic information—with little or no expectation for reciprocity. This kind of relational behavior exists because it has been highly effective in the past in ensuring the continued existence of one’s genetic information. People who possessed genes that predisposed them to behave altruistically (to show love) to others who shared their DNA (children, siblings, cousins, and so on) have historically passed on greater amounts of their genetic information, genetic information which contained these same altruistic genes, to future generations. As Gottschalk states regarding altruistic genes replicating altruistic genes, “The solution . . . is to think in terms of genes and to get altruistic genes to benefit themselves by benefiting other bodies which contain copies of the altruistic gene” (Gottschalk 2002, 270).

Viewed from a different direction, those humans (kin selection has not been selected for by many other species, but it has been selected for among humans) that possessed genes for, say, abandoning their offspring to fend for themselves after birth, were out reproduced by those who were endowed with genes that promoted altruistic behavior toward their offspring after birth. Thus, kin selection amongst humans has generally been a more effective reproductive strategy than, say, abandonment selection or universal love selection. Ultimately, because this behavior is so effective, it essentially became the norm amongst humans. It should be noted that kin selection is simply an effective means to propagate genes into the future, and it does not hold moral superiority over, say, utilitarian theory advocated by Peter Singer (1981) and Joshua Greene (2013), which asserts that people, families, and societies be more inclusive in the care of others.

The genes that generate these neurocognitive mechanisms that promote this behavior exist because these genes are highly effective in propelling genes (themselves) into the future (Dawkins 1976). From a Darwinian perspective, it could be argued, to love someone is to invest altruistically in their genetic success/reproductive success—invest one’s time, emotional energy, resources, and fitness—to engage in Confucian family centrism—so that another person, almost always another blood relative,3 can survive, become more reproductively fit, and pass on genetic information.

B. The Cinderella Effect

The “Cinderella effect” explains that the likelihood of a child being abused or killed by a parent is far higher when that parent is a not genetically or biologically related. Rates of child abuse in stepparent families far exceed that of biologically intact families (Daly and Wilson 1988; Schnitzer and Ewigman 2008; Stiffman et al. 2002). Stiffman et al. estimates that children “were eight times more likely to die” (2002, 615) at the hands of a non-genetically related adult living in their household when compared to a household that consisted of an intact, two biological parent arrangement.

Evolutionarily speaking, when a parent abuses their biologically related child, the chances for that child to be successful in the propagation or continuation of the abusive parent’s genes later in life is reduced (consider the reproductive implications of severe brain trauma from physical abuse or severe emotional and psychological abuse; the significance of this abuse extends to the death of the child, in that, if the child is killed his/her reproductive capacity is reduced to zero). Because the child, under these adverse conditions, has a reduced chance of propagating his/her genes, the genetic predisposition for this abusive behavior from a biological parent is greatly diminished—the genes that promote abusive behavior from parents to their biological children are more likely not to survive into future generations.

On the other hand, when a non-biologically related parent (usually the stepfather) abuses a stepchild, that behavior will often not affect the continuation of his abusive genes, and, thus, it will not affect the continuation of this type of abusive behavior. Gottschalk and Ellis (2010, 66) explain, “From an evolutionary perspective, individuals who harm close genetic relatives are less likely to pass genes on to future generations than are individuals who harm distant relatives or nonrelatives.” In one of nature’s sad twists, the stepparent’s abusive behavior may help in the propagation of his abusive genes. By abusing his non-genetically related child, he is, in effect, forcing that child away from him, away from the home he shares with the child’s biological mother, and, most importantly, away from his resources, so that he can begin to propagate his own genes with the child’s mother and share his resources with his biological children.

This same type of behavior is witnessed repeatedly in the animal kingdom, usually on a more vicious level. When an alpha male lion gets old or shows vulnerability, another male lion will emerge, kill or drive away the alpha, take over the pride, and then usually proceed to kill all the previous alpha’s cubs and begin to mate with the lionesses—starting the process of passing on his genetic information. Killing all the previous alpha’s cubs also precipitates a renewed sexual receptivity amongst lionesses.

Therefore, when parents raise their own biological children (showing love in the Confucian sense), the likelihood for child abuse is much lower than if the mother were to take a member of the outside community into the home to interact with and raise her children (Daly and Wilson 1988). The propensity for a relative to show love to a genetically related child, and, at the same time, not abuse the child, is significantly higher than a non-genetically related person. This is because the genetically related pair share a great proportion of the same genetic information and that genetically related relative wants that genetic information to prosper and propagate. The propensity for a non-genetically related person to show love to the child, and not abuse them, is reduced because they do not carry the same genetic information and, thus, this person is likely to be less concerned about the child’s future reproductive success. This all likely operates on a subconscious level. Daly and Wilson summarize this reduction in affection due to genetic differences, “One implication is that substitute parents will often care less profoundly for “their” children than will genetic parents” (1988, 520).

The Cinderella effect is an indication of how difficult it is to overcome the inherent disposition to favor our own kin over others, wherein seemingly good and well-meaning genetically unrelated parents may become twisted due to unconscious evolutionary mechanisms and neglect, mistreat, and even abuse their unrelated children. Given this difficulty, accepting and improving on the Confucian family centric disposition may be of benefit. The Cinderella effect is also evidence of how the implementation of Confucian family centrism—wherein fathers remain with their families to raise, monitor, punish, and educate their own children, rather than have outsiders into their former homes to engage in this behavior—may produce more favorable outcomes for their children and for society. A united and engaged biologically related parenting framework (which is foundational to Confucian family centrism) is seemingly optimal for children, as kin selection and the Cinderella effect show, thus, likely making it easier to implement within society.

III. Parenting Styles

Confucian family centrism was tested by examining different parenting configurations to determine which arrangements reduced and which arrangements increased the probability for delinquency and other negative life outcomes. Baumrind (1966) promoted three main parenting styles, each encompassing a different degree of Confucian family centrism. These three styles are permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian and they are employed in a NLSY97 question to respondents in the current study. Maccoby and Martin (1983) later expanded on Baumrind’s work with a two-dimensional parenting framework that included an “uninvolved” parenting style; this uninvolved style is also included in the NLSY97.

The following is an articulation of Baumrind’s three parenting styles plus Maccoby and Martin’s uninvolved style, all of which are combined in the NLSY97 and tested in the current study:

Permissive parenting: exerts limited control over children. Fathers engage their boys in a more relaxed, generous, friendly, and placating manner, working to appease their boys with gifts, good cheer, and acceptance rather than through supervision, moral lessons, and discipline. Permissive fathers severely blur the hierarchical boundaries between themselves and their boys, diminishing, though not necessarily eliminating, the controlling and educational value of Confucian style hierarchies. Permissive parenting provides limited Confucian family centrism with a relatively warm and relaxed parental disposition.

Authoritative parenting: this type of parenting represents the quintessential form of Confucian family centrism. Authoritative fathers engage in unswerving supervision and discipline, transmit and enforce moral standards of behavior through education, help their children when required, and praise their children’s achievements. These authoritative fathers have a disciplinarian orientation, but it is generally instructive and motivational in nature. It generates a distinct hierarchy between fathers and their boys. The more authoritative the parenting, the more distinct the father-son hierarchy. Though, this authoritative parenting has limits. If it becomes too strongly authoritative and disciplinarian, combined with a lack of compassion and a lack of educational properties, it gravitates into authoritarian parenting.

Authoritarian parenting: involves stern and overt discipline with little regard for the education or the development of children. It is harsh discipline without the Confucian centric investment in the emotional and cognitive health of children. Fathers set strict guidelines for the behavior of their boys and detail the responses for failing to follow the guidelines. Authoritarian fathers provide little by way of a healthy Confucian centric education for their boys; they make clear the obligations but do little to develop and educate their boys when the boys fail to meet these obligations.

Uninvolved parenting: provides limited affection and almost nonexistent constraints over children. Fathers abnegate most parental responsibilities, namely those involving education, supervision, and attention, though they still provide the essentials (shelter, food, funding, and so on) for their children to survive. Uninvolved fathers provide little discipline and no education for boys. This type of laissez-faire parenting is far removed from Confucian family centrism.

IV. Current Study

If Confucian family centrism is instrumental in reducing the likelihood that boys engage in delinquency and criminality, then the main question is the following: Do Confucian centric parenting practices positively influence behavioral outcomes among boys?

To respond to the existing research gaps, the present study examined whether two NLSY97 parenting questions: 1) The residential fathers parenting style, and 2) The degree of parental monitoring by the residential father, each possessing different types of parenting, influence boy’s levels of delinquency, substance use, behavioral/emotional problems, and stealing. The following are the NLSY97 parenting variables along with their corresponding hypotheses:

A. The Residential Fathers Parenting Style

Four parenting styles were examined in the residential fathers parenting style question: authoritative, permissive, uninvolved, and authoritarian. The authoritative parenting style is most closely aligned with Confucian family centrism, as it provides a clear and firm father-son hierarchy with educational development.

Hypothesis 1: Authoritative parenting possesses clear Confucian family centric elements; thus, it will produce the lowest probabilities for a) delinquency, b) substance use, c) behavioral/emotional problems, and d) ever steal anything greater than $50 including cars.

Hypothesis 2: Uninvolved and authoritarian parenting do not possess clear Confucian family centric elements; thus, they will produce higher probabilities for a) delinquency, b) substance use, c) behavioral/emotional problems, and d) ever steal anything greater than $50 including cars.

B. The Degree of Monitoring by the Residential Father

Confucian family centrism closely and effectively monitors the conduct of boys for purposes of control, discipline, punishment, and education.

Hypothesis 3: Monitoring scores NLSY97 range from 0 to 16; higher scores indicate greater parental monitoring. Monitoring behavior in the 10 to 15 range is best representative of Confucian family centrism; a score in the 16 range will be overly variable, possibly because of unhealthy parenting pressure, the “child effect” rather than the “parent effect,” or other issues found in scores on extreme ends of extended Likert scales. Thus, scores in the 10 to 15 range will produce the lowest probabilities for a) delinquency, b) substance use, c) behavioral/emotional problems, and d) ever steal anything greater than $50 including cars.

V. Methodology

The data used for the current study was derived from the first wave of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 97 scores, which were taken in 1997. The NLSY97 is a program of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics that tracks the lives of a sample 4,599 males born between 1980-84. Respondents, with an initial age range of 12-16, are being surveyed longitudinally, beginning in 1997 to the present time.4

As suggested by Cramer and Bock (1966), a two-way MANCOVA was conducted on the means to help protect against inflating the type 1 error rate in the follow-up ANOVAs and post-hoc comparisons. A two-way MANCOVA was conducted to test the effects of two independent variables: 1) residential fathers parenting style 2) degree of parental monitoring by the residential father, on four dependent variables: 1) delinquency scores 2) substance use 3) behavioral/emotional problems, and 4) ever steal anything greater than $50 including cars, while controlling for race/ethnicity, year of birth, the age of the biological mother when she had the first born, gross household income in the past year, net worth of the household according to the parent, biological fathers highest grade completed, biological mothers highest grade completed, and mothers parenting style.

A test using Mahalanobis Distance with a critical value of .001 identified no outliers, so no outliers were removed from the dataset.

A. Independent Measures: The Fathers Parenting Practices

The following are the two NLSY97 parenting variables that provide different methods of parenting:

The “parenting style” question was presented to the participants thusly: “Residential Father’s Parenting Style. 1 = Uninvolved, 2 = Permissive, 3 = Authoritarian, and 4 = Authoritative.”

The “degree of parental monitoring of the residential father” question was presented to the participants thusly: “Degree of parental monitoring of the residential father. Scores range from 0 to 16; higher scores indicate greater parental monitoring.”

B. Dependent Measures: Boys Moral and Behavioral Variables

The following are the four NLSY97 variables that were used to measure boys moral and behavioral outcomes:

The question of “delinquency” was presented to the participants thusly: “Delinquency score index. Scores range from 0 to 10; higher scores indicate more incidents of delinquency.”

The question of “substance use” was presented to the participants thusly: “Substance use index. Scores range from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate more instances of substance use.”

The question of “behavioral/emotional problems” was presented to the participants thusly: “Behavioral and emotional problems scale for boys. Scores range from 0 to 8; higher scores indicate more frequent and/or numerous behavior problems.”

The question of “ever stealing anything greater than $50 including cars” was presented to participants thusly: “Have you ever stolen something from a store, person or house, or something that did not belong to you worth 50 dollars or more including stealing a car?” Scores were coded: 1 = yes, 0 = no.

VI. Results

A. Parenting Style on Delinquency, Substance Use, Behavioral/Emotional Problems, and Stealing

A statistically significant multivariate test was obtained from parenting style, Pillais’ Trace = .046, F (12, 3015) = 3.93, p < .001, η2p = .02.

Adjusted Mean, Std. Error, and 95% Confidence Interval for Residential Father’s Parenting Style (Youth Report)

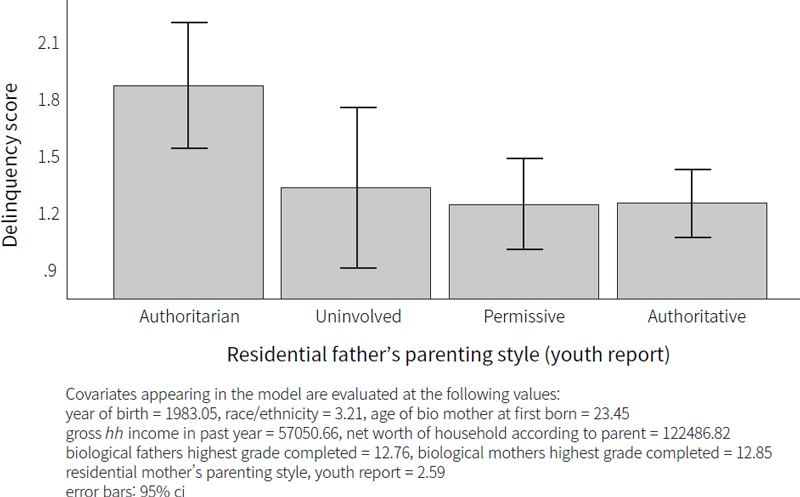

Univariate testing indicated that there was a significant difference among the four parenting styles (uninvolved, permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian) on delinquency scores (delinquency scores range from 0 to 10; higher scores indicate greater incidents of delinquency), F (3, 1006) = 3.33, p = .019, η2p = .01. Post hoc comparisons using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference test indicated significant differences between two groups of parenting styles, wherein authoritative (M = 1.27), permissive (M = 1.26), and uninvolved (M = 1.34) parenting had significantly lower delinquency scores compared to authoritarian (M = 1.88) parenting.

As shown in figure 1, uninvolved, permissive, and authoritative parenting produced the lowest probability for delinquency and were significantly different from authoritarian parenting.

Univariate testing indicated that there was no significant difference among the four parenting styles (uninvolved, permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian) on substance use (substance use scores range from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate greater substance use), F (3, 1006) = 1.00, p = .393, η2p = .003.

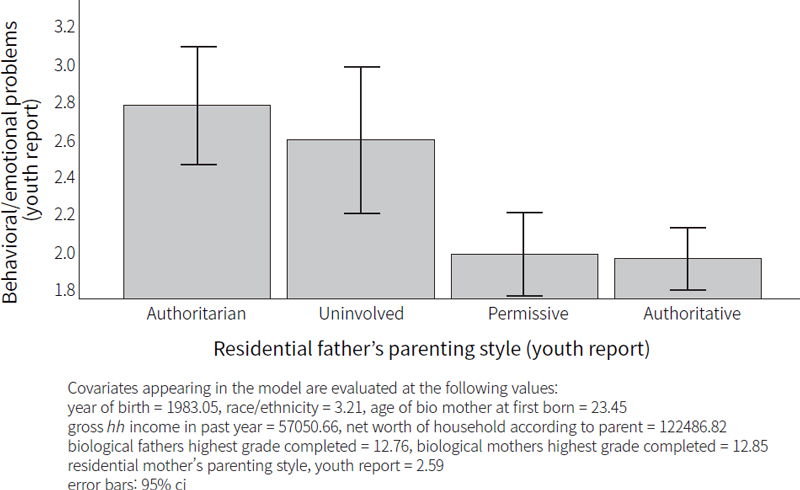

Univariate testing indicated that there was a significant difference among the four parenting styles (uninvolved, permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian) on the behavioral/emotional problems scale (scores range from 0 to 8; higher scores indicate more frequent and/or numerous behavior/emotional problems), F (3, 1006) = 8.02, p < .001, η2p = .02. Post hoc comparisons using Fisher’s LSD test indicated significant differences between two groups of parenting styles on boys behavioral/emotional problems, wherein authoritative (M = 1.96) and permissive (M = 1.99) parenting had significantly lower behavioral/emotional problems compared to authoritarian (M = 2.78) and uninvolved (M = 2.60) parenting.

As shown in figure 2, authoritative and permissive parenting, though not different from each other, were significantly different from authoritarian and uninvolved parenting for behavioral/emotional problems. Uninvolved and authoritarian parenting produced the greatest probability for behavioral/emotional problems, and they were not significantly different from one another.

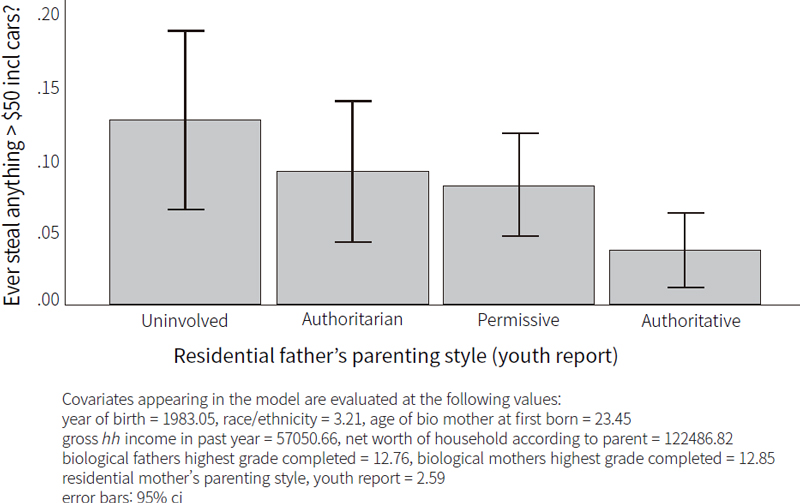

Univariate testing indicated that there was a significant difference among the four parenting styles (uninvolved, permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian) on stealing (yes = 1, no = 0), F (3, 1006) = 8.02, p = .002, η2p = .01. Post hoc comparisons using Fisher’s LSD test indicated significant differences between two groups of parenting styles, wherein authoritative (M = .04) parenting had significantly lower stealing scores compared to uninvolved (M = .13) and permissive (M = .08) parenting.

As shown in figure 3, authoritative parenting produced the lowest probability for stealing and was significantly different from uninvolved and permissive parenting.

B. Degree of Parental Monitoring by the Residential Father on Delinquency, Substance Use, Behavioral/Emotional Problems, and Stealing

A statistically significant multivariate test was obtained from degree of parental monitoring by the residential father, Pillais’ Trace = .15, F (64, 4024) = 2.12, p < .001, η2p = .04.

Adjusted Means, Std. Error, and 95% Confidence Interval for Degree of Parental Monitoring by Residential Father (Youth Report)

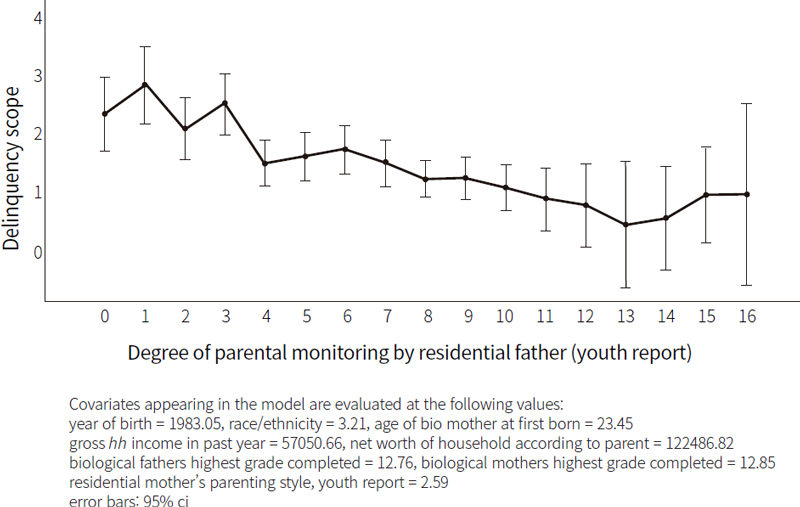

Univariate testing indicated that there was a significant difference among the degree of father monitoring on delinquency scores (delinquency scores range from 0 to 10; higher scores indicate greater incidents of delinquency), F (16, 1006) = 4.29, p < .001, η2p = .06. Post hoc comparisons using Fisher’s LSD test indicated significant differences between two subsets of father monitoring, wherein monitoring levels of 0 (M = 2.33) through 3 (M = 2.50) had significantly higher delinquency compared to levels 8 (M = 1.23) through 15 (M = .96).

As shown in figure 4, monitoring behavior in the 8 to 15 range had the lowest probability for delinquency from boys. Monitoring behavior in the 0 through 3 range had the greatest probability for delinquency. A monitoring score in the 4 to 7 range produced a probability for delinquency that fell between these two groups.

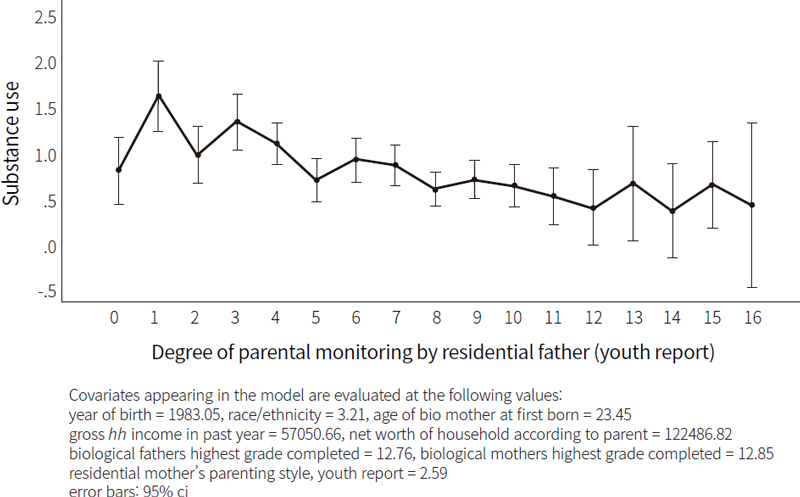

Univariate testing indicated that there was a significant difference among the degree of father monitoring on substance use (substance use scores range from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate greater substance use), F (16, 1006) = 3.61, p < .001, η2p = .05. Post hoc comparisons using Fisher’s LSD test indicated significant differences between two subsets of father monitoring, wherein monitoring levels of 1 (M = 1.63), 3 (M = 1.34), and 4 (M = 1.11) had significantly higher substance use compared to levels 8 (M = .61) through 12 (M = .41).

As shown in figure 5, monitoring behavior in the 8 through 12 range had the lowest probability of boys engaged in substance use. Monitoring behavior in the 1, 3, and 4 range had the greatest probability for substance use. A monitoring score in the 5 to 7 range produced a probability for substance use that fell between these two groups.

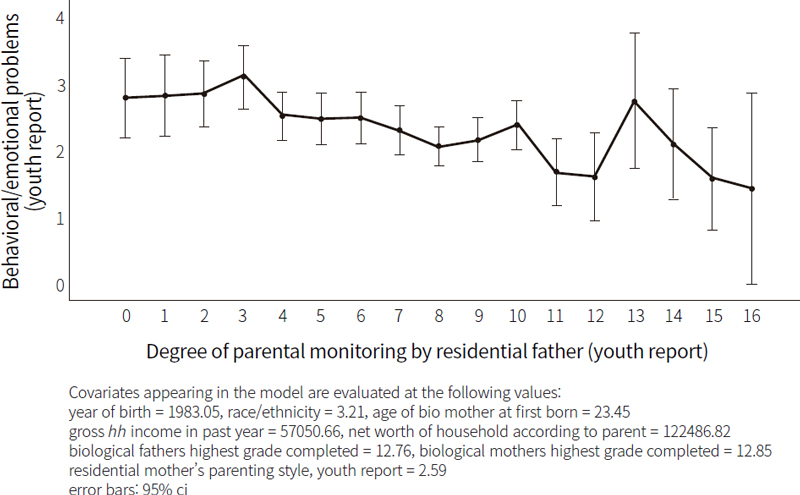

Univariate testing indicated that there was a significant difference among the degree of father monitoring on boys behavioral/emotional problems (behavioral/emotional scores range from 0 to 8; higher scores indicate more frequent and/or numerous behavior/emotional problems), F (16, 1006) = 2.51, p = .001, η2p = .04. Post hoc comparisons using Fisher’s LSD test indicated significant differences between two groups of father monitoring, wherein monitoring levels 0 (M = 2.79) through 6 (M = 2.48) had significantly higher behavioral/emotional problems compared to levels 11 (M = 1.69), 12 (M = 1.61), and 15 (M = 1.59).

As shown in figure 6, monitoring behavior in the 11, 12, and 15 range had the lowest probability for behavioral/emotional problems from boys. Monitoring behavior in the 0 through 6 range had the greatest probability for behavioral/emotional problems. A monitoring score in the 7 to 10 range produced a probability for behavioral/emotional problems that fell between these two groups.

The Effect of Parental Monitoring by the Residential Father on Boy’s Behavioral/Emotional Problems* Fathers monitoring scores range from 0 to 16; higher scores indicate greater monitoring.** Behavioral/emotional scores range from 0 to 8; higher scores indicate more frequent and/or numerous behavior/emotional problems.

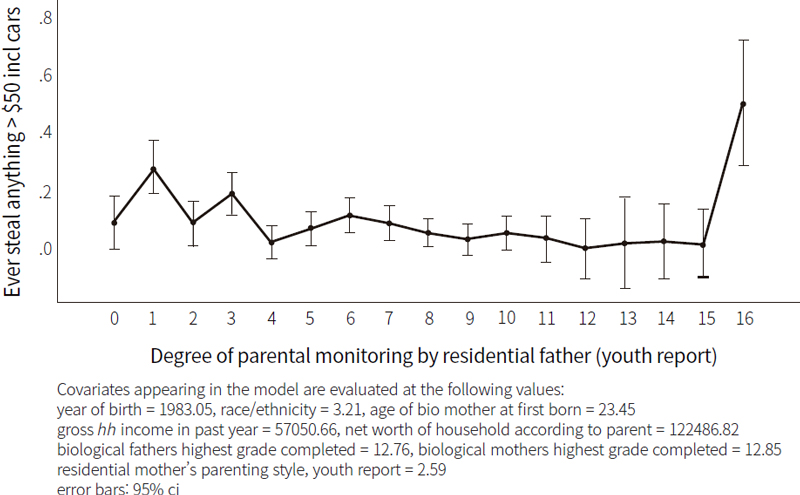

Univariate testing indicated that there was a significant difference among the degree of father monitoring on stealing, F (16, 1006) = 3.51, p < .001, η2p = .05. Post hoc comparisons using Fisher’s LSD test indicated significant differences between two groups of father monitoring, wherein monitoring levels 1 (M = .28) and 3 (M = .187) had significantly higher stealing compared to levels 7 (M = .08) through 12 (M = -.002).

As shown in figure 7, monitoring behavior in the 7 to 12 range had the lowest probability for stealing among boys. Monitoring behavior in the 1 and 3 range had the greatest probability for stealing.

VII. Discussion and Conclusion

The authoritative parenting style is representative of Confucian family centrism, and it likely produces the most promising psychological and social outcomes for boys, specifically in the realm of delinquency, behavioral/emotional problems, and stealing. The more Confucian family centric the fathering, the better the life outcomes for boys. If the father-son relationship becomes so intense, disciplinarian, uncaring, and noneducational that it reaches the level of authoritarian parenting, then negative life outcomes among boys will likely significantly increase. There seems to be only so much pressure and discipline boys can undergo before they rebel. Conversely, the more uninvolved or disinterested the parenting style, the more removed the parenting is from Confucian family centrism, the more that negative outcomes increase.

With both the extremes of uninvolved and authoritarian parenting considered unhealthy and weak/overly strong alternatives to Confucian family centrism, it leaves permissive parenting as the only other real competing parenting arrangement. Permissive parenting is relatively effective because there is real parenting and parental investment taking place (unlike uninvolved parenting), there may be some hierarchic functioning between father and son, and it is not overtly harmful parenting (like the authoritarian parenting style). Though somewhat effective, it is likely not as effective as Confucian family centrism in educating boys to properly navigate society. This is because it doesn’t put into place a strong and healthy hierarchical framework, it doesn’t set explicit boundaries and limits that are closely monitored with the prospect for discipline and punishment for crossing these boundaries and limits, and it doesn’t work to effectively educate on morality and social behavior through discipline.

High levels of parental monitoring by fathers, monitoring being a major component of Confucian family centrism, appears to significantly reduce delinquency and other negative life outcomes.

Three major claims are made here: First, authoritative fathering, representative of Confucian family centrism, produces lower rates of delinquency, behavioral/emotional problems, and stealing among boys. Second, higher levels of monitoring of boys by fathers, representative of Confucian family centrism, produces lower rates of delinquency, substance use, behavioral/emotional problems, and stealing among boys. Third, Confucian family centrism, within the confines of the variables explored in this paper, produces lower rates of delinquent and other problematic behavior among boys.

When fathers are not in the lives of their boys, are overly permissive or authoritarian in their parenting, or when they fail to effectively monitor behavior—when they are not engaged in Confucian family centrism—the ability for boys to later participate in society in a productive way is likely diminished. When boys are unable to properly operate, compete, and succeed in societies many hierarchies and competitive arenas, when they fail to climb the necessary hierarchical structures required to obtain reasonable social positions, they often turn to crime and gang activity as means to collect resources, achieve some form of social standing (even if it is standing among criminals), to lash out at a system that requires what they were denied/unable to provide, or some other criminal means to adapt to their circumstances (Cloward and Ohlin 1960; Cohen 1955: Merton 1938). Ultimately, it is Confucian family centrism and the Confucian parenting practices encompassed within, during the early stages of boy’s development, that appears to play a significant role in how boys later function within society.

The parenting dynamic takes place in a multifaceted social and economic environment consisting of many variables that may affect delinquency and other behavioral outcomes. It is important to note the complex relationships inherent in parenting and future behavior. Confucian family centrism, i.e. authoritative parenting with high levels of monitoring, may be statistically linked with outcomes for boy’s in ways that are not accounted for in the parenting dynamic. Parenting and the boy’s responses to it may be linked because each one is a product of the same underlying variables, such as the family’s sociodemographic makeup, teen parenthood, parent education, the boy’s age, gender, and so on (Hay et al. 2006; Kesner and McKenry 2001; Pratt, Turner, and Piquero 2004). Additionally, the link between certain kinds of parenting and the boy’s outcomes may be a product of “child effects” rather than “parent effects”—in that, boy’s behavior may generate different kinds of parenting. To view Confucian family centrism as the overwhelming force determining future delinquency and criminality is to potentially miss a larger confluence of factors that may or may not conspire to be influential. Lastly, there may be some incongruity between using crime data derived from subjects in the United States to test the influence of Confucian theory. Future studies may employ crime data gathered from Confucian societies to test Confucian theory.

References

-

Baumrind, D. 1966. “Effects of Authoritative Parental Control on Child Behavior.” Child Development 37: 887-907.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1966.tb05416.x]

-

Bell, D. A., and T. Metz. 2011. “Confucianism and Ubuntu: Reflections on a Dialogue between Chinese and African Traditions.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 38: 78-95.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6253.2012.01690.x]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. 2019. “National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 cohort, 1997-2017 (rounds 1-18).” Produced and distributed by the Center for Human Resource Research (CHRR). Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University.

-

Bloom, I. 1997. “Human Nature and Biological Nature in Mencius.” Philosophy East and West 47: 21-32.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1400248]

- Braithwaite, J. 2003. Restorative Justice and Responsive Regulation. New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Braithwaite, J. 2015. “Rethinking Criminology through Radical Diversity in Asian Reconciliation.” Asian Criminology 10: 183-191.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-014-9200-z]

-

Cheng, C. Y. 1948. “The Chinese Theory of Criminal Law.” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 39: 461-470.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1138459]

- Cloward, R. A., and L. E. Ohlin. 1960. Delinquency and Opportunity. New York: Free Press.

- Cohen, A. 1955. Delinquent Boys. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Confucius. (1893) 1971. Confucian Analects, The Great Learning, and the Doctrine of The Mean, translated by J. Legge. New York: Dover Publications.

- Confucius. 2003. Analects, translated by E. Slingerland. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Confucius. 2008. The Analects, translated by R. Dawson. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Cramer, E. M., and R. D. Bock. 1966. “Multivariate Analysis.” Review of Educational Research 36: 604-617.

[https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543036005604]

-

Daly, M., and M. Wilson. 1988. “Evolutionary Social Psychology and Family Homicide.” Science 242: 519-524.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3175672]

- Dawkins, R. 1976. The Selfish Gene. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gottschalk, M. 2002. “Evolution and the Sociology of Punishment.” PhD diss., University at Albany, State University of New York.

-

Gottschalk, M., and L. Ellis. 2010. “Evolutionary and Genetic Explanations of Violent Crime.” In Violent Crime: Clinical and Social Implications, edited by C. J. Ferguson, 57-74. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

[https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349305.n4]

- Greene, J. D. 2013. Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap between Us and Them. New York: Penguin Press.

-

Hay, Carter, et al. 2006. “The Impact of Community Disadvantage on the Relationship between the Family and Juvenile Crime.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 43: 326–356.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427806291262]

-

Kesner, J. E., and P. C. McKenry. 2001. “Single Parenthood and Social Competence in Children of Color.” Families in Society 82: 136-143.

[https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.210]

-

Kim, S. 2015. Confucianism, Law, and Democracy in Contemporary Korea. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield International.

[https://doi.org/10.5771/9781783482252]

- Lan, F. 2015. “Humanity and Paternal Eros: The Father-Son Relationship in Comparative Perspective.” Frontiers of Philosophy in China 10: 629-646.

- Lee, L. T., and W. W. Lai. 1978. “The Chinese Conceptions of Law: Confucian, Legalist, and Buddhist.” Hastings Law Journal 29: 1307-1303.

- Legge, J. 2016. The Book of Rites. The Bilingual Reading of the Chinese Classic. Beijing: Zhongzhouguji chubanshe.

- Liu, J. 2007. “Principles of Restorative Justice and Confucian Philosophy in China.” Newsletter of the European Forum for Restorative Justice 8: 2-3.

- Liu, Q. 2007. “Confucianism and Corruption: An Analysis of Shun’s Two Actions Described by Mencius.” Dao 6: 1-19.

- Maccoby, E. E., and J. A. Martin. 1983. “Socialization in the Context of the Family: Parent-Child Interaction.” In Socialization, Personality and Social Development, edited by E. M. Hethering, vol. 4 of Handbook of Child Psychology, edited by P. H. Mussen, 1-101. New York: Wiley.

- Mencius. 2004. Mencius, translated by D. C. Lau. London: Penguin Books.

-

Merton, R. 1938. “Social Structure and Anomie.” American Sociological Review 3: 672–682.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2084686]

- Misc. Confucian School. 1879. The Sacred Books of China: The Texts of Confucianism. Part I of the Shu King, the Religious Portions of the Shih King, the Hsiao King, translated by J. Legge. Oxford: Clarendon Press. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2162, (accessed February 1, 2021).

- Mo Zi. 2014. The Book of Master Mo, translated by I. Johnston. New York: Penguin Books.

-

Nichols, R. 2011. “A Genealogy of Early Confucian Moral Psychology.” Philosophy East and West 61: 609-629.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2011.0057]

-

Pratt, T. C., M. G. Turner, and A. R. Piquero. 2004. “Parental Socialization and Community Context: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Structural Sources of Low Self-Control.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 41: 219–243.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427803260270]

-

Schnitzer, P. G., and B. G. Ewigman. 2008. “Household Composition and Fatal Unintentional Injuries Related to Child Maltreatment.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 40: 91-97.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00211.x]

- Singer, P. 1981. The Expanding Circle: Ethics and Sociobiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, H. 1991. The World’S Religions. San Francisco: Harper.

-

Stiffman, M. N., et al. 2002. “Household Composition and Risk of Fatal Child Maltreatment.” Pediatrics 109: 615-622.

[https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.109.4.615]

-

Trivers, R. L. 1971. “The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism.” Quarterly Review of Biology 46: 35-57.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/406755]

- Xunzi. 1999. Xunzi, translated by J. Knoblock and J. Zhang. Hunan: Hunan People’s Publishing House.