Contentious Source: Master Song, the Patriarch’s Voice

© Institute of Confucian Philosophy and Culture, 2021

Abstract

This paper introduces Song Siyeol, known as Master Song (Songja 宋子), who had a great influence on Korean philosophy and politics in late Joseon (18-19th century). Among his Great Compendium, there are substantial body of writings and comments related to women. As his views directly and indirectly contributed to shaping orthodox Korean Neo-Confucian views regarding women, his writings are an invaluable resource for understanding women and gender in the late Joseon period. This paper presents his views on women, focusing on issues related to rituals. By highlighting and analyzing the issues discussed regarding the role of women in four traditional family rituals, I delineate ways in which Song Siyeol positioned women in his ritualist metaphysics and use this analysis to examine his philosophical approach, which reflects his views on, and understanding of, women, gender, and associated philosophical concepts, while making meaningful and practical discoveries that can be embraced and implemented by women and people today.

Keywords:

Song Siyeol, family rituals, women, Joseon, Korean Neo-ConfucianismI. Introduction

This paper introduces Song Siyeol 宋時烈 (1607-89), a seminal figure in late Joseon 朝鮮 (1392-1910) Korean philosophy and politics, known as Master Song (Songja 宋子), who left behind a substantial body of writings and comments related to women. His views directly and indirectly contributed to shaping orthodox Korean Neo-Confucian views regarding women, making Song Siyeol’s writings an invaluable resource for understanding women and gender in the late Joseon period. This paper presents his views on women, focusing on issues related to rituals. By highlighting and analyzing the issues discussed regarding the role of women in four traditional family rituals, I delineate ways in which Song Siyeol positioned women in his ritualist metaphysics and use this analysis to examine his philosophical approach, which reflects his views on, and understanding of, women, gender, and associated philosophical concepts. This study presents two distinctive challenges: (1) how to contextualize patriarchal voices in ways that avoid demonizing his view as simplistically patriarchal and (2) finding ways to articulate the complex nature of the issues and ideas in play while making meaningful and practical discoveries that can be embraced and implemented by women and people today.

II. The Life and Thought of Song Siyeol

Song Siyeol, pen name Uam 尤庵, is a representative and authoritative figure in the Korean Confucian tradition. He is known as “the Juja 朱子 (C. Zhuzi) (1130-1200) of Korea” and played an important role in determining the spirit of the age in Confucian theories of righteousness (ui 義; C. yi) and ritual propriety (ye 禮; C. li).1 King Jeongjo 正祖 (r. 1776-1800) honored him as Master Song and ordered the publication of the collected works of his writings under the title of the Great Compendium of Master Song (Songja daejeon 宋子大全). Later, in a record of his death (卒記), Korean Confucians praised him as the legitimate successor of the Way that began from Confucius (孔子, 551-479 BCE) and was transmitted through Ju Hui 朱熹 (C. Zhu Xi), Yi I 李珥 (1536-84; pen name Yulgok 栗谷), and Gim2 Jangsaeng 金長生 (1548-1631; pen name Sagye 沙溪) (Great Compendium of Master Song 151.39b-40a).3

Song, at the same time, is one of the most problematic figures in Korean philosophy and politics. He served four kings as a royal mentor and advisor and was the head of the Westerners (Seoin 西人), a philosophical and political faction of his age. At the same time, his views and practices were considered orthodox, conservative, and strict. His stringent and unyielding attitude brought him both immense respect as a great teacher of the time as well as harsh criticism from opponents. Late Joseon politics was deeply intertwined with philosophical and scholarly views, and factional differences regularly caused purges of members of whichever side was out of favor, who were accused of deviating from the correct way of Confucianism. The seventeenth-century ritual controversy (yesong 禮訟) over the proper mourning ritual for King Hyojong 孝宗 (r. 1649-59) exemplifies how such controversies intertwined philosophical debates and political struggles. In this case, the disagreement resulted in his own death; the king ordered that he be sent poison to take his own life, which he did.

Song Siyeol is also an important person in the history of Korean women.4 He played a significant role in the extension and strengthening of the agnatic principle (jongbeop 宗法; C. zongfa) that embodies patrilineal, patrilocal, and patriarchal ideology and practices. He produced a considerable number of writings on women in a variety of genres, such as letters to his female relatives, tomb inscriptions and condolences, and sacrificial writings. The women in his writings range from royal and gentry family women to slaves. His writings on upper-class women present his public views on women, while those concerning his family members and slaves offer his personal or private views on women, and this complicates an interpretation of his philosophy.

The influence of Song’s views and writings extended far beyond his lifetime. His answers on ritual matters related to women were received as an authoritative source for later Confucians and included in the collection of commentaries on the Family Rituals in the Extended Interpretations to the Family Rituals (Garye jeunghae 家禮增解).5 His letter to his eldest daughter became a new and influential source concerning women that later Korean Confucians followed as a tradition to teach their female relatives.6 Later generations of his school produced two remarkable women Confucian philosophers, Im Yunjidang 任允摯堂 (1721-93) and Gang Jeongildang 姜靜一堂 (1772-1832), who not only were born into families aligned with his faction, but also, as scholars, inherited and continued his teachings, including those on rituals.

Song and his writings are a rich source for understanding the perspectives and attitudes of male Confucians about women and for understanding the influence his teachings had on later women. We should neither neglect nor accept what he said blindly. A sympathetic reading of such traditional sources, which were shared by both women as well as men of the time, combined with an understanding of the complicated contexts in which they were produced and an awareness of one’s standpoint will clarify his philosophical views and prepare the way for new research and contemporary insights regarding women and Confucianism.

As a feminist re-reading, this essay is informed by feminist philosophers’ criticisms and alternative reading strategies for reading male philosophers. In order to avoid falling into the pitfall of being overly deferential to tradition, feminist philosophers suggest rethinking the questions through which history is structured, focusing and drawing out the “unthought” assumptions and attitudes informing a text, including its omissions and paradoxes with the clear goal of achieving “an active philosophical engagement with a text rather than the backward-looking activity of trying to determine the exact meaning of a historical text” (Witt and Shapiro 2020). Feminist scholars of Asian philosophy caution against succumbing to a new imperialism represented by Western feminism and the importance of embracing Confucianism as a shared heritage for members of the East Asian diaspora should be kept in mind as well.7

III. Explanation and Analysis

To examine the relationship between ritual and women in Confucian –ism, four family rituals—capping/hair-pinning, marriage/wedding, funeral/mourning, and sacrifice—are the best place to begin because these rituals concern life within the family, the site where women led their lives.8 Women performed and participated in family rituals as prescribed in the Confucian texts, embodying the ideological and social expectations laid down by Confucianism. Though the Confucian ritual canons unavoidably reflect a male-centered perspective, in a number of significant ways, these four family rituals also express the Neo-Confucian ideal of universalism based upon their newly developed metaphysics of pattern-principle (i 理; C. li). These rituals mark turning points in human life—becoming an adult, forming a family, and death—and these apply regardless of social status or gender. This important universalist dimension of Neo-Confucianism, unfortunately and ironically, also gives rise to forms of gender disparity within Confucianism.

In order to understand the apparently contradictory Confucian views on women in relation to ritual, these topics and the process of philosophizing should be clearly demonstrated and analyzed in connection to other related issues and ideas. Until now, only a few contemporary scholars have brought these issues together.9 The lack of this kind of more comprehensive and synthetic scholarship is partly due to the difficulty of understanding the ritual discussions of the times from a philosophical perspective. They are like puzzles manifested in scattered passages and discussions and represented by theorization that was only partially developed in an organized or systematic way and focused specifically on women. In these puzzles, gender is only one determinant that is intermingled with other determinants, such as age and social class. Moreover, each family ritual was connected with several others within the larger Confucian worldview. They cannot be understood in isolation from one another or from the expression they receive on a single occasion. In the following section, I offer a brief introduction to each of the four rituals I have chosen to explore and its meaning, interweaving these introductions with Song Siyeol’s writings, which are introduced in Section V.

In Confucianism, one’s maturation is marked more with ritual than the unfolding of physical development, and the initiation or coming-of-age ceremony is the very first ritual in one’s life. The Book of Rites says that “Capping is the beginning of ritual propriety” (Zheng and Kong 1999, 1883).10 The stages described in the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonies mark one’s transition from childhood to adulthood by prescribing changes in caps and clothes.11 Through the ritual, one transforms oneself as “the human body cum vessel” (Zito 1997, 47) and becomes a participant in a bigger and wider society. Women’s initiation, the hair-pinning ritual (gyerye 笄禮; C. jili), was made an independent ceremony by Ju Hui and regarded as a complement to men’s capping. Before him, women’s hair-pinning (gye 笄; C. ji) was mentioned only as a part of wedding ritual, saying that when “a woman is promised in marriage, she has a pinning ceremony and also obtains a pen name.”12 In Ju Hui’s Family Rituals, for the first time, we learned the details of hair-pinning.

Song Siyeol continued Joseon Neo-Confucian efforts to transform what they regarded as barbaric local customs into the refined and elegant culture of China by implementing and practicing family rituals, including initiation. The initiation ritual was de facto in disuse because it required highly abstract ideological understanding and commitment rather than simple physical behavior. Confucian initiation calls on one to commit one’s life as a Confucian in consciousness, self-cultivation, and the actualization of Confucian ideals in everyday life. Even elite members dedicated to Confucianism in eighteenth-century Joseon Korea did not perform the capping ceremony.13 When Song Siyeol performed it, it presented an extraordinary scene and dramatic precedent for contemporary Neo-Confucians.14

Not surprisingly, women’s hair-pinning received much less attention. Song’s writings mentioned hair-pinning only thirteen times, while the character for capping appears forty-four times. Yet, what must be noted is that Song Siyeol carried out a hair-pinning ritual for his female relatives as a way to promote Confucianism. His practice of hair-pinning was and remained influential to his students and later followers. For example, Yun Bonggu 尹鳳九 (1683-1767) notes that Song Siyeol, in his later years, had his female relatives perform a pinning ritual (Yi 2011, vol. 2, 218-19).15 Gwon Sangha 權尙夏 (1641-1721), the foremost pupil of Song Siyeol, states that “Master Uam’s family already practiced this ritual. [The example of the Master] can be a [good] example” (Yi 2011, vol. 2, 218-19).16 Though there is only limited source material on the subject, an analysis of Song’s writings on hair-pining can allow us to draw meaningful observations that can be used for future and more thorough philosophical interpretation.

The first translation below introduces Song Siyeol’s answer to Yi Gunhoe 李君晦. Yi seems to have been reading the hair-pinning section in Ju Hui’s Family Rituals. The basic principle Ju Hui taught was that “the procedure [of hair-pinning] is the same as in the capping ritual (yeo gwallye 如冠禮; C. ruo guanli).” But the procedures were not entirely identical. He omits several rites for women, such as the provision of an assistant for a sponsor and the presentation of the initiate to the elders. Yi’s questions concern these omissions. For capping, Ju Hui prescribed a helper for both a sponsor and a presider. But, for hair-pinning Ju Hui said not to use an assistant for the sponsor, without mentioning an usher—whose role was to serve as a helper for the presider. Song Siyeol urged Yi to strictly follow what Ju Hui “wrote.” The logic behind this is to do the “same” with the capping, making the changes stated by Ju Hui.

The second omission is “presentation of the initiate to the elders” right after the ceremony. The Letters and Etiquette (Seoui 書儀; C. Shuyi) by Sama Gwang 司馬光 (C. Sima Guang) (1019–86) retained this rite, saying “Once [she] had hair-pinning, [she] visits and bows to only her father and all mothers, aunts, and siblings. The remaining [procedures] are the same as in a man’s capping ritual” (Sima, n.d., 2.8a)17 But Ju Hui eliminated the presentation to the elders without providing any reason for doing so. Song Siyeol accepted Ju Hui’s omission but felt the need to explain it. And so, he cites Mr. Wang’s comment, “Young women are very shy” as justification for omitting the presentation of young women to the elders. Mr. Wang’s comment was intended to explain the reason why a female initiate must have an assistant (Yi 2011, vol. 2, 225),18 but neither Song Siyeol nor his disciples speculated any further. A later Korean Neo-Confucian, Gwak Jongseok 郭鍾錫 (1846-1919), discussed this issue further, arguing that the presentation should not be skipped because it was a ritual responsibility for all adults. He suggested that presentation to the elders was not repeated in the description of the hair-pinning ritual because in the Family Rituals the rite was already demonstrated in the case of man’s capping (Gwak, n.d., 49.10a).19

It is easy to trace the connections among several related concepts and ideas: presentation to the elders, women’s shyness, and responsibility of adults. The presentation of an initiate symbolizes the realms that are appropriate for her or him in life as an adult. A young woman who has come of age is presented to her father and all mothers, aunts, and siblings because her proper realm is within the family. A young man is presented to a wider range of relatives as well as non-relatives as he is to take his place in the public realm. It is thought that a young woman might feel “shy” and would be emotionally immature to be presented to this larger range of people. But male initiates were encouraged to overcome their self-centered and emotional reaction in accordance with ritual propriety, to take their place and to become full members of social communities. Song Siyeol essentialized women as shy and immature in both moral and ritual senses embedded this essentialized belief and attitude in the hair-pinning ritual.

The second translation deals with the issue of adulthood. The questions of Min Saang’s 閔士昂 (1640-92) make clear that one’s adulthood is fully ritualized in Confucianism. Maturity is not determined by one’s biological age and development. Rather marriage, forming one’s own family, which includes having children and thereby continuing the succession of life and lineage, is more important; it even determines the ways in which one’s death is treated. Another significant point is that marriage is also highly gendered. In the case of women, it is not marriage itself, but engagement that is of paramount importance. Song Siyeol points out that, unlike the ancients, later generations regarded a woman who has completed the hair-pinning ritual but dies before reaching twenty-years old as suffering a “premature death” (sang 殤; C. shang). Such is not the case for men. Moreover, for women who have yet to reach the age of twenty, “being promised” is a pre-condition for hair-pinning. In a man’s case, engagement did not have the same weight. A man’s capping occurs at the age of twenty, regardless of whether he was engaged or not. These differences and pre-conditions manifest the gendered nature of these rituals.

An analysis of Song Siyeol’s writings on the hair-pinning ritual offers us a way to glimpse ritualized adulthood and its gendered aspects. In Confucianism, physical maturity is not the sole or at times even the primary factor determining a person’s adulthood. The requirements and details of the ritual procedures of men’s capping and women’s hair-pinning were differentiated. The gendered differentiation reflects beliefs about their different realms of life as adults and their emotional and ethical maturity. The omissions and differences deserve further theoretical development in contemporary Confucian philosophy for a more gendered-equal future.

In regard to marriage, we introduce two writings concerning the sixtieth wedding anniversary and clan exogamy. Song Siyeol’s reply to Gwon Chido is a rare textual record about the 60th wedding anniversary. We learn that this ceremony began to be celebrated among literati family around Song’s time. He acknowledges the ceremony as a joyful occasion for children to have both parents enjoy longevity. But he questions whether it is appropriate to perform this ritual. He bases his concern on two principles: textual evidence and his conception of gender. Song first argues that there is no textual reference that shows ancient sages taught that people should hold a ritual for a sixtieth wedding anniversary, though they did celebrate long life. This at least implies that the rite is not in accordance with the heavenly Way nor “matches the pattern-principle of human beings.”

In relation to gender, he brings up the wine pouring rite (chorye 醮禮; C. jiaoli) and stresses that it should be performed only once in woman’s life, “given the meaning of its very name.” The name, cho 醮, first appeared as a part of the capping and wedding ritual in the Etiquette and Ceremonies. According to Jeong Hyun’s 鄭玄 (C. Zheng Xuan) (127-200 CE) commentary, a superior—sponsor and parents–pours a cup of wine for inferiors, an initiate or bride and groom. The act of wine pouring is a one-way commemoration that is not to be repeated or returned, thereby departing from reciprocity, the standard principle of ritual propriety.

The character cho also meant “even and equal” (je 齊; C. qi). To the passage about marriage in the Book of Rites, Jeong Hyun added a comment, “Je 齊 means that [a bride and groom] eat together of the same sacrificial animal, thereby becoming equal. Je sometimes is written as cho 醮” (Zheng and Kong [n.d.]1999, 949).20 Yu Hyang 劉向 (C. Liu Xiang) (77-6 BCE)’s the Biography of Exemplary Women replaced 齊 with 醮, when it cited the line from the Book of Rites. Later Song Neo-Confucians adopted this line into the Elementary Learning. The Ming Confucian scholar Jin Ho’s 陳澔 (C. Chen Hao) (1260-1341)’s Collected Commentaries of Elementary Learning (Sohak jipju 小學集注; C. Xiaoxue jizhu) supports this line of interpretation, saying that an assistant for the wedding ritual pours wine for the bride and groom three times, but does not exchange (Zhu and Chen, n.d., 4.13a).21 The very meaning of cho is either a marriage, which bans women’s remarriage, or a one-way, non-reciprocal ritual.

The fourth selection discussed below concerns marriage between people with the same surname. From the beginning of Joseon dynasty, Korean Confucians put great effort into transforming certain native Korean customs. One of their exemplary projects in this regard was to ban marriages between people with the same surname and uphold a policy of clan exogamy, because sharing the same surname meant sharing the same gi 氣 (C. qi) material passed down through a patriline. Song Siyeol took this effort a step further and strongly argued for a ban on marriages between people with the same surname, even in cases when the people involved had different ancestral seats. His main argument was that the different ancestral seats still originated from the same ancestor, and therefore these people would be sharing the same gi-material.

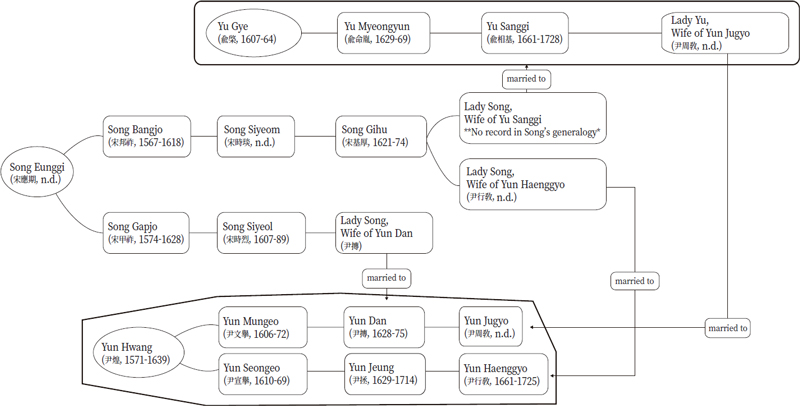

Song’s reply to Wonseok raises two interesting and meaningful points for contemporary readers: the relationship between marriage and factional struggle and a woman’s perspective on marriage. In Korea, as elsewhere, marriage has been a way to create or maintain societal status and relationships. Sometimes marriage between members of different political factions was expected to soften or, at least, prevent the tension between them from intensifying. During the Joseon dynasty, as factions subdivided, tensions between them grew, because the ways to sagehood that each prescribed were perceived to be different and opposing factions regarded one another as diverging farther and farther from the correct way. Song Siyeol and Yun Jeung 尹拯 (1629-1714) used to be teacher and disciple, but, later, their relationship broke up over several issues. In the end, the split between them led to the subdivision into the Patriarch (Noron 老論) and the Youth (Soron 少論) factions. Song Siyeol’s letter concerns the complex marriage connections between people with three surnames: Song, Yun, and Yu (兪). In order to understand the marriage ties, we need to see from the perspective of women in these three surnames as in the following Diagram.

The two people in the arranged couple are Yun Jugyo 尹周敎 (n.d.) and Lady Yu (Daughter of Yu Sanggi 兪相基, 1651-1728). As shown in Diagram 1, which is aligned patrilineally, the couple bears two different surnames, and their relationship sounds quite distant; therefore, the marriage, which was arranged by Song Siyeol, does not seem to pose any problem. But the problem occurs when we look at this relationship from their mothers’ perspectives. The groom’s mother is the daughter of Song Siyeol and the bride’s mother is the daughter of Song Gihu 宋基厚 (1621-74). These two mothers have a common ancestor, Song Eunggi 宋應期 (n.d.). This makes the couple stand in the relationship of maternal uncle and niece in the clan of Song.

The letter shows that the marriage was considered inappropriate. The inappropriateness was not because of factional differences, at least ostensibly, but the relationship between two of the women involved was regarded as problematic, which Song Siyeol criticized the practice as an Eastern22 [native] custom. “People [still] get startled and consider strange [marriages] with the relatives who are more distant than the eight- or nine-chon (寸)”23 (Great Compendium of Master Song, n.d., 51.28a).24 He mentioned cases of marriage between maternal uncles and sororal nieces, and cross-cousin in the Ju Hui family as a precedent for his proposed marriage. He noted that all of these are fully in accordance with the practices of Confucian sages and worthies and so such marriages cannot be contrary to righteousness. Further complicating the situation, Yun Jeung’s father, Yun Seongeo 尹宣擧 (1610-69), a close friend of Yun Hyu’s 尹鑴 (1617-80), had criticized Ju Hui and claimed he was unacceptable as an authority to decide whether the marriage is appropriate or not.

The letter sheds light on women’s perspectives in several ways. First, the marriage tie was questioned based on the consanguine relationship between two women. This is an important issue because it challenges patrilineality and emphasizes the shared gi-material between the two women. Second, Song Siyeol’s daughter sent him a letter, expressing her doubts about his position. A woman and a daughter questioning her father, who was a highly authoritative figure, using vernacular Korean, offers a rare chance to glimpse how active and expressive women could be on matters of ritual.

The fifth and sixth writings presented below concern Song Siyeol’s views on mourning rituals, throughout which sacrifices are offered for the deceased. Deciding who would serve as a presider at such rituals was an extremely sensitive issue and gender mattered in the decision. The fifth writing discusses who could serve as an appropriate presider over such sacrifices when a man died without a son. The presider’s name is inscribed on the spirit tablet of the deceased, and detailed rites and forms are decided depending on who serves as the presider. The decision is also related to the deceased’s place in the ancestral hall, which reflects one’s spiritual position in his lineage. Therefore, the topic had great symbolic value.

Song Siyeol raises questions concerning how to proceed in cases involving adoption. If a son is to be adopted to be an heir for the deceased man, his wife can preside over the sacrifices “for the time being.” Still, the temporality of this arrangement is stressed. The temporal nature of the arrangement is connected with establishing the next heir through patrilineal adoption. Though Song Siyeol acknowledged the wife’s eligibility to preside, the purpose was to fill the gap between the dead husband and his future son, who was selected from his descendant group. In other words, allowing the wife to be a presider of her husband’s mourning was to maintain and protect her deceased husband’s right to succession, and her act of establishing an heir may even have been interpreted as a symbolic act of procreation.

Procreation is the main purpose of the marriage ritual, the union of man and woman. Confucianism regarded the procreative function and the ritually appropriate process of taking a woman as a mother of the future heir as important (Zheng and Kong [n.d.] 1999, 1888).25 For these reasons, the wife’s ritual status was considered important and not to be violated. If a woman was the primary wife of the eldest son of the family, a presiding man, she served at the sacrificial ritual along with him as his ritual partner. Earlier, Korean custom had allowed the wife to preside over sacrifices, but Korean Neo-Confucians questioned whether this was appropriate26 and the debate had continued until the time of Song Siyeol.

Song Siyeol acknowledged the wife’s eligibility to preside over the sacrifices, but, at the same time, he stressed the temporal nature of this arrangement. Song changed the point of the discussion, focusing on the necessity to accelerate the process of establishing an heir to resolve the issues Gim Gan raised. Song supported his arguments with the authority of a former worthy’s opinion, citing the opinion of his teacher, Gim Jangsaeng 金長生 (1548-1631), whose pen name is Sagye 沙溪 and who was known as a master of ritual in Korea. In addition to ritual canons, Ju Hui’s Family Rituals, Gim Jangsaeng’s Uirye munhae 疑禮問解 (Questions and Answers on Doubtful Passages of the Rites) were used as second level canons to support his argument. Yet, when Gim Gan asked further questions about the case of a wife, Song Siyeol did not pursue the issue and closed the topic by saying, “This is not something that others [outsiders] can decide.” His response can be read as an indirect way of dismissing further inquiry on the issue.

According to Song, even though fraternal succession is decided and, as a result, the wife of the deceased has lost her ritual status as the partner of her deceased husband, she is still obligated to observe a three-year mourning period for her husband. In general, in the course of the three-year mourning period, the two good fortune sacrifices are held at the thirteen and twenty-fifth month, and the peace sacrifice at the twenty-seventh month, respectively. When a brother becomes the presider, the duration of the mourning is one year. Therefore, in such cases, the wife seems to lose the opportunity to offer her good fortune and peace sacrifices. Regarding this matter, Song Siyeol replied simply “although we say that his younger brother presides over the sacrifice, since his wife wears the three-year mourning attire, how can there be no good fortune or peace sacrifice?” What did he mean by this statement? Did he mean that the wife should keep wearing her mourning attire even after the official mourning period which was decided and conducted by the presider, who was supposed to be the closest person, thereby owing the heaviest mourning duty to the deceased, the brother? If so, that might violate another ritual principle. Yet, neither Song Siyeol nor Gim Gan expressed any further opinions on this topic.

The sixth translation offered below is a response to Hong Uju, another student of Song Siyeol. This letter discusses women in relation to mourning in more detailed ways. Song Siyeol confirms that a wife should be buried at her husband’s family cemetery, referring to this as an “unchanging ritual (常禮).” He denies the wife’s connection to her daughter’s family for burial. A daughter and a daughter’s son can preside over the wife’s mourning ritual as presiders, but Song makes it clear that this is not a “correct ritual.” The daughter and daughter’s son’s presiding are compared with that of a neighbor serving in the same role. If a wife dies without an heir, anyone can preside over her funeral, so why not her daughter or her daughter’s son? But, if there is any male relative from her husband’s clan, her daughter or her daughter’s son dare not preside. The daughter was allowed to preside temporarily as a part of custom. Still, Song Siyeol strongly argues that she cannot alter or create a rite based on “one’s imagination when there is no rite [regarding it].” His arguments directly imply the necessity to establish an heir.

Examination and analysis of Song Siyeol’s two writings on mourning ritual reveal several new and important aspects related to women. Searching for supporting references in ritual classics and canons is an ongoing principle to decide and evaluate ritual propriety. When a question arose, Song Siyeol and his students tried hard to find answers by drawing upon such texts. Song Siyeol provided his expertise on ritual issues, not only by appealing to pertinent passages and views from canonical texts but also by evaluating and deciding which issues are worth discussing further or not. We also find him advancing a transitional view on women’s eligibility to preside over sacrifices as a part of mourning ritual. A wife was in the process of losing her ritual eligibility to preside over her husband’s funeral even though her eligibility was connected to the symbolic procreation she offered to her husband’s family. The gradual loss of her ritual status in her husband’s family was confirmed when Song Siyeol found a textual reference supporting such an interpretation in the writings of a former worthy.

The seventh and eighth selections from Song Siyeol offered below discuss issues related to sacrificial ritual. The seventh writing was a response to Yi Junggeo’s 李仲擧 (fl. 1699) questions regarding the case of the Vice Academic Counselor’s family. It seems that the Counselor’s son had died, and his grandson was about to succeed the lineage heirship. But the eldest grandson died without a son. In this case, who should offer sacrificial rites to him, his wife or younger brother? The younger brother expresses his great concern about offering such sacrifices, saying “If I preside over the sacrificial rite [for my brother] hastily, people might suspect me of trying to dispossess the legitimacy [of his heir].” This line clearly shows that the legitimacy of the succeeding line was a tremendous concern for Neo-Confucians. Toward the end of Joseon period, the orthodox way of succession became more difficult to establish because not every male heir succeeded in bearing a son from his primary wife. Korean Neo-Confucians tried to resolve this issue through adoption. As the second grandson said, the family would wait until one of the dead man’s younger brothers gives birth to a son and establish that boy as the deceased’s heir. As this practice became accepted and settled, the wife of the deceased began to lose her power over adoption. Earlier, the wife would have more say in decisions concerning adoption, but the situation changed around mid-Joseon. Because her ritual status was connected with other rights, such as over property, the tension between the wife and the younger brother of the deceased heightened around the time of Song Siyeol.27

Song Siyeol’s writing presents two main arguments to support the legitimacy of the younger brother. “There is no mention of a woman presiding over sacrificial rites in the ritual [classics]” and a passage about “substituting for the presider” (seopju 攝主) in the Toegyjip 退溪集 (Collected Works of Toegye). The character 摄 means to substitute. In Mencius 5A4, this character is used to describe the relationship between the two sage-kings, Yo 堯 (C. Yao) and Sun 舜 (C. Shun). “When Yo was old, Sun substituted for him.” The following line says, “Confucius said, ‘There are not two suns in the sky, nor two sovereigns over the people.’” This line provides an ideal for succession for the later Confucians. Yi Hwang 李滉 (1501-70), whose pen name is Toegye, also states that the younger brother can temporarily serve as substitute for the deceased older brother as a seopju 攝主. Toegye’s statement became a canonical reference for Song Siyeol and Song’s students further developed this idea by searching for more textual references supporting it.

The eighth and last writing of Song Siyeol presented below offers a slightly different perspective on women’s ability to perform a sacrificial ritual. The passage translated is part of his letter to his eldest daughter, who married into a prestigious family. As a father, he seems to be greatly concerned about her. His concern was not about her actual ability; it arose out of his emotional reaction as a father. This letter was written in vernacular Korean, which is quite rare as it is written by a male Confucian. The content includes his admonition concerning the way to serve at a sacrificial rite. The list of issues it discusses is quite detailed, such as self-care and how to take care of the people involved. His letter shows how important the role of a wife was in offering a sacrificial ritual. Not only the virtue of her heart-mind but also the good fortune of the whole family was in the hands of a wife.

There are several noteworthy issues in this last writing for modern readers to note and draw upon. A woman was expected to serve not only her husband’s family but other people, such as friends of her husband or father-in-law, as well. This expectation probably originally was based on an ideal of male friendship, according to which each was to take care of the other. In order to actualize trustworthiness (sin 信; C. xin) between men, women’s labor and sincerity were expected. If a woman’s offering was insincere or impure, the harm would reach her whole family. This emphasis on a wife’s obligation to a broad range of others connected with her husband looks ironic when compared with the offerings she was to make for her natal parents. Highlighting a woman’s virtue and its serious effects on her husband’s family, yet underlining the incomplete filial piety based on the temporality and informality of her officiation contradicts the core teaching of Confucianism, filial piety.

These two writings reveal subtle changes in women’s eligibility to officiate at a sacrificial ritual. Women as daughters lost their rights to officiate at sacrificial rites for their natal parents during the first half of Joseon dynasty. By the time of Song Siyeol, a daughter’s and her son’s officiation were regarded as unacceptable. Women as wives began to lose their right to officiate at their husband’s sacrificial rites before they establish an heir for their husbands that was customarily accepted. Song Siyeol searched for canonical references that would deny women’s ability to officiate and to legitimize a younger brother’s substitution. Yet, he advocated for the patriarchal expectation of women to serve friends of her husband and father-in-law as if they were her own. As a result, he deprived women’s filial piety for her natal parents but added an additional duty of “sincerity” only for her husband’s descendant group. The changes shown in Song Siyeol’s views are significant because his comments were accepted as standard by later Joseon Neo-Confucians. In the Extended Interpretations to the Family Rituals, for example, his comments were treated as establishing de facto unchanging rites.

IV. Conclusion

This essay analyzes eight pieces of writing of Song Siyeol, a monumental figure in the history of Korean Confucianism. His views and comments on four family rituals related to women also had a long-lasting impact on the later period of the Joseon. The eight examples confirm key characteristics of and provide new insights in relation to ritual and women in Korean Neo-Confucianism.

When he was asked about ritual matters, Song always looked back to textual canons for support. The texts to which he appealed include ancient Confucian classics, such as the Book of Rites and the Etiquettes and Ceremonies, and the works of later worthies, such as Ju Hui’s Family Rituals. This serves to reconfirm the influence of Ju Hui and his Family Rituals. Song Siyeol also looked to the writings of Korean worthies, including Toegye and Sagye to help support his view in which patrilineal and patriarchal formation and the arrangement of families based on agnatic principle clearly are highlighted. Song Siyeol developed his view to deprive women of their ritual eligibility. His stance exerted significant influence on later Confucian scholars who further developed and canonized this view, which was stated clearly in his discussions on mourning and sacrificial rituals.

These passages offer new findings, both negative and positive. For example, his discussion of the sixtieth wedding anniversary is extremely rare and valuable. Among other things, from it we learn the origin and details of the customary ritual. Song Siyeol’s theorizing process shows his gendered approach, which re-affirms the ban on women’s remarriage. His view that repeating the wedding rite, even with the same man, constitutes a case of re-marriage is original and interesting. For women, the number “one” had a literal meaning, and its impact is life transformative. Regardless of the partner, woman must marry only “once” throughout her lifetime.

Song’s writings also lend new insights on women’s voices and perspectives. His letter on remarriage was written in vernacular Korean, Hangeul. This work is most significant for modern researchers studying Confucianism and women. More importantly, through his writings we learn that women sometimes expressed their opinions on ritual issues directly to powerful men. Female relatives of the Song clan declared their discomfort about the marriage he had proposed from the perspective of women who shared the same gi-material. Song Siyeol’s daughter did not hesitate to send a letter to express her own opinion to contend to her father, who was the authoritative master of Confucian ritual.

In this essay, I have presented only parts of Song Siyeol’s writings focusing on the four family rituals in relation to women. Among the hundreds of volumes of his writings, many are yet to be translated into modern Korean much less English. This essay showcases some of the kinds of issues the great master Song discussed and how he theorized his arguments and views. At the same time, the analysis reveals that his writings should be read from multiple perspectives. Some of his views simply reconfirm traditional male-centered ideals but others manifest new insights into the detailed process of philosophizing and women’s own voices.

The writings of Song Siyeol, an authoritative figure in Korean Confucianism and especially in regard to women, are patriarchal. Some scholars might find them contentious to include into resources for contemporary society. However, it would be too simplistic and dismissive to judge all and every aspect of his writings as bearing a voice of a patriarch. While some of his work strengthened a patriarchy both theoretically and ritually, Song Siyeol also created a space where women could participate in discussion and practice with more agency, though limited. Therefore, his writings can and should be used as a valuable resource to understand the gendered philosophizing process and to draw out the hidden voices of and for women.

The new findings can contribute to the re-imagining of a future of Confucian family rituals in contemporary life from the perspective of women. Some of family rituals, such as sacrificial rites and wedding ceremony, remain practiced widely in many East Asian societies. East Asian diaspora communities have brought Confucian rituals as a part of their heritage and show a great interest in reviving or keeping practicing them in non-Confucian societies such as the U.S. and Europe. Song Siyeol’s writings will provide us a way to distinguish the patriarchal side from the positive aspects, and thereby allowing us to implement or imagine Confucian rituals more creatively for a better future of all people regardless of one’s gender.

V. Selected Translations from the Works of Song Siyeol

1) Great Compendium of Master Song (Songja daejeon 宋子大全), 99:8b

Reply to Yi Gunhoe 李君晦 (n.d.)28

Ju Hui’s commentary on the line “the sponsor arrives,” says “an assistant is not used” (不用贊者).29

[Gunhoe asked] “Is an usher30 also not used?”

[The Master answered] The “Pinning Rite” [section in the Family Rituals] only says not to use an assistant. And so, an usher should be used.

In regard to the choice of words [in the prayer,] the commentary suggests using “female literatus” (yeosa 女士; C. nüshi).31

[Gunhoe asked] “What does it mean to call a woman a ‘literatus’ (sa 士; C. shi)? For a woman, is there a rite to present her to the elders after her pinning [ceremony]?”

[The Master answered] “‘female literatus’ is an [honorific] title used to refer to a woman who performs [the role of] a literatus. As for why there isn’t a rite to present [a woman] to the elders [after her pinning ceremony], according to Mr. Wang [the reason is that], ‘Young women are very shy.’ Is this perhaps also the reason that the Family Rituals omits this rite?”

2) Great Compendium of Master Song (Songja daejeon 宋子大全), 86.38b-39a.

[Min Saang 閔士昂32 asked] “Those who die before they complete their nineteenth year are said to suffer a ‘premature death’ (sang 殤; C. shang). If a man who already has had his hair capped or a woman her hair pinned [dies before they complete their nineteenth year], even though [they] are not yet married, should [their relatives] wear the mourning attire prescribed for an adult (成人) for them?”

[The Master answered] “The Family Rituals says that, ‘A man who has married or a woman who has been engaged [who dies before they complete their nineteenth year] is not regarded as having suffered a premature death.’33 The reason why [the passage] focuses on ‘having married’ instead of saying ‘having a capping rite’ as the main criterion is because at that time [when Master Ju lived] men who bore and supported children and then completed the capping rite were still not considered adults. Therefore, in the case of a man, [the Family Rituals] made this determination based on whether he had married. In the case of a woman, [the Family Rituals] made this determination based on whether she had been promised in marriage. According to ritual propriety, once a woman is promised in marriage, she has a pinning ceremony. And so, pinning and capping were regarded in the same way in the ancient rituals. But it is different for later generations. Even though a woman has completed the hair-pinning rite, if she [dies before she is] twenty years old, she is not regarded as having suffered a premature death. In the case of a man, he must be married; only then is he referred to as an adult.”

3) Great Compendium of Master Song (Songja daejeon 宋子大全), 88.35b-36a.

Reply to Gwon Chido34

On the 28th day of the 11th month in the Byeongin year (1686)

The rite for the 60th wedding anniversary that you asked about started among literati families recently. It is certainly a rare and happy occasion for a family to have both parents reach such an advanced age. Every time I hear about a family performing this rite, my orphaned and lonely heart35 is sorely grieved and wounded. But, thinking about the time when the three dynasties flourished, people enjoyed great longevity and there were many centenarians. This was why there was a ritual in which [the Son of Heaven] “inquired about those who were 100 years old.”36 Since it is said that a man “at 30 has a wife,”37 when he reaches 90 years old, that will be the exact year of his 60th wedding anniversary. Now, if what custom prescribes accords with the heavenly Way and matches the pattern-principle of human beings, then the sages necessarily would have made regulations and forms [about this] and taught them to the people.

Moreover, speaking from the perspective of a wife, to perform the wine pouring rite (chorye 醮禮; C. jiaoli)38 more than once does not seem appropriate, given the meaning of its very name. I fear we should not let people get used to using this name. Nevertheless, given the feelings that people’s children have, they cannot pass this day indifferently; it would be fine to raise a glass and celebrate it, regarding it as roughly similar to the celebration of a birthday; there will be no harm in doing so.

Generally speaking, in regard to this kind of matter, one must first decide whether it should be performed or not. Afterward, one can ask whether to wear [ritual] attire or not. If one says that it can be performed and must be done, then one should refer to the passage, “Oneself and the presiding man of the wedding do not have any mourning duty beyond a year” [before getting married], that is found in the Family Rituals,39 and arrange things accordingly.

4) Great Compendium of Master Song (Songja daejeon 宋子大全), 129.11a-12a

Reply to Wonseok 元錫 (n.d.)40 in the tenth month of Jeongmyo year (1687)

The wedding day of my grandson [Jugyo 周敎], [the scion of the lineage] Yun 尹, is not far away. The day before yesterday, Garim 嘉林41 sent his maternal uncle, who brought his mother’s42 letter, written in vernacular Korean. It seems that things [in regard to the wedding] will not work out [smoothly]. At first, when Mr. Yu 兪43 met [Yun] Jeung [尹]拯 (1629-1714) in person and asked [about the wedding], [Jeung] replied, that there was not any problem. Later, though, he tried to entice and threaten him in a hundred different ways, seeking to change his mind. When [Yu] did not listen, [Jeung] devised a scheme to break the marriage. He counterfeited a letter, written in vernacular Korean, in order to upset the Yu family. It is just like him to do such a thing.44 I only lament that my uncle’s offspring participated in the deceit.

I have also heard, as you said in the letter, that slanders [against me] are getting more malicious. However, [your news that someone accused me of] “calling in a foreign enemy and choosing a date to attack the palace”45 arrives too late.46 What difference does that make now? Moreover, at the time, I knew there would be such slander. Nevertheless, Master Ju married his daughter’s son, Hwang Ro 黃輅 (C. Huang Lu) (n.d.), to his son’s daughter. Moreover, he said, “[Those with] the same surname originally are close, but they grow distant as the generations pass. [Those with] different surnames originally are distant, but later, through marriage, they become close.”47 Generations of people from No 魯 (C. Lu) married people from Song 宋 (C. Song) and Je 齊 (C. Qi). Among their marriages, some were between maternal uncles and sororal nieces48 [due to repeated marriage relationships]. How could Master Ju mention it, if it was contrary to righteousness? Moreover, is there anything to discuss between the Yuns and the Yus regarding “maternal uncles and sororal nieces?” This is all only the Yuns, repeating and mimicking the wicked Yeo 驪兇,49 who says that, “Master Ju does not offer an adequate model to follow.” That is why [they] slander me like this. When I was not moved by their slander, they came up with a vicious plot. This is the same kind of clever scheme that Na Yangjwa 羅良佐 (1638-1710) employed when he forged a letter in my name in order to frame Mungok 文谷.50 I do not know what kind of troubles there will be later on. How dreadful! How dreadful!

5) Additions to Great Compendium of Master Song (Songja daejeon burok 宋子大全附錄), 15.499a-b

Records of Gim Gan 金榦 (1646-1732)51

[Gim] Gan asked, “if [someone] dies without a son, and is only survived by his wife and brother, who should preside over the sacrifices [for him]?”

The Master said, “if there is the intention to establish an heir for him, his wife should preside, for the time being. If [there is] not, the rite of fraternal succession should be followed. After the younger brother has performed the sacrifice, the spirit tablet of the deceased should be installed52 in the appropriate place [in the sacrificial hall]. Then [it is] complete.”

Gan asked, “now if his younger brother presides over the sacrifice, that means there will be no] good fortune (sangje; C. xiangji 祥祭) or peace sacrifice (damje; C. xuanji 禫祭).53 What about this?”

The Master said, “although we say that his younger brother presides over the sacrifice, since his wife wears the three-year mourning attire, how can there be no good fortune or peace sacrifice?”

Gan asked, “regarding the section concerning inscribing the tablet (jeju 題主; C. tizhu), the Ritual classic has terms such as Illustrious Ruler (hyeonbyeok 顯辟; C. xianpi) and Illustrious Brother (hyeonhyeong 顯兄; C. xianxiong), etc.54 How should we decide what is the proper way to refer to the one presiding [at his rite]?”

The Master said, “Those [issues] are discussed in the Questions and Answers on Doubtful Passages of the Rites (Uirye munhae 疑禮問解).55 The so-called Illustrious Ruler is not an orthodox rite (正禮).”

Gan asked, “Since this is not an orthodox rite, it will be difficult to inscribe the designation56 of the deceased and the presider before establishing an heir.”

The Master said, “It seems best to establish an heir as soon as possible and then inscribe the name of the presider [on the spirit tablet].”

Gan asked, “In cases where an heir has not currently been established, and we must wait for the time being to do so later on, once an heir has been established, how should we handle the spirit tablet that was inscribed earlier?”

The Master said, “This is not something that others [outsiders] can decide.”

In the year of 1673, Records of Words in Seogyo (Seogyo eorok 西郊語錄)

6) Great Compendium of Master Song (Songja daejeon 宋子大全), 117.31b-32a

[Excerpts from] Reply to Hong Uju 洪友周 (n.d.)57

It is an unchanging ritual (常禮) to bury a wife at her husband’s family [cemetery]. How could we bury her at her son-in-law’s family [cemetery]! It is possible to not have an heir (後) at one’s funeral, but there must be a presider. Even neighbors and the headman of the neighborhood can preside at [one’s] funeral,58 so why not a son of her daughter? Nevertheless, if there is any relative from the same clan,59 [the daughter’s son] dare not preside. Master Ju (Juja 朱子; C. Zhuzi) clearly taught that a son of a daughter cannot offer [sacrificial] offerings and confirmation can be found in [ritual] regulations and forms.

Still, if the deceased family has not yet established an heir, a married daughter may offer food temporally. That is a customary rite that sometimes happens. However, it is not a correct ritual. [The case in which] she did not pull back the stool and the mat when the daughter’s mourning period had come to an end is far more difficult to feel at ease with. Who dares to create [a rite based on] one’s imagination when there is no rite [regarding it]! It would be better to establish an heir as soon as possible.

7) Great Compendium of Master Song (Songja daejeon 宋子大全), 119.5a-b.

[Master Song] Reply to Yi Junggeo 李仲擧 (fl. 1699)60

The eldest grandson of the Vice Academic Counselor (bujehak 副提學) Gim Gyeong-yeo 金慶餘 (1596-1653) died without an heir. His second grandson should offer sacrificial rites [to him]. But, as the wife of the eldest son is still surviving, the second grandson dared not to offer a sacrificial rite [for his brother], saying “my sister-in-law will adopt an heir sooner or later. If I preside over the sacrificial rite [for my brother] hastily, people might suspect me of trying to dispossess the legitimacy [of his heir]. I must wait until one of my brothers gives birth to a son and he is established as my [deceased] brother’s heir.” Since it is unavoidable, the mother [of the future adoptee] can preside temporarily. This way [we can] abide by the principle of strictly securing the legitimacy [of his future heir]. Yet, there is no mention of a woman presiding over sacrificial rites in the ritual [classics]. I had always harbored doubts about this and wished to ask someone who knows ritual propriety about it. Now the letter you sent perfectly tallies with [my question] concerning this issue. It is as if someone had asked about what is correct and was able to attain a definitive account. It was fortunate that your letter reached me! I had come across the Collected Works of Toegye, which has a passage about “substituting for the presider (seopju 攝主).”61 Since it mentions the [character] seop 攝, it means that the [younger] brother temporarily can serve as a presider at sacrificial rites. There is no harm [in him doing so].

8) The way to serve at a sacrificial rite62

Purity and cautiousness are the most important [concerns] when performing sacrificial rites. When preparing offerings, do not worry about anything [other than following].

Do not scold slaves.

Do not laugh loudly or show concern on your face.

Do not employ illicit means to obtain what you lack.

Do not let even a speck of dust fall onto the offerings.

Do not eat [the offerings] first nor give them to a whining child.

Prepare only as much as you need because too much food naturally will become unclean.

If you think you will not have enough food, plan ahead for the year’s sacrificial rites, so no rite will be missed. [In this way, you will] not make an obvious display of abundance or shortage.

Comb your hair and take a bath with sincerity even in winter.

Do not wear colorful clothes for the rite on the day of a death anniversary (gijesa 忌祭祀).

Cut your fingernails and toenails and keep them clean.

[If you take care of the sacrificial rites in this way] the spirits [of the ancestors] will accept the offerings and bring good fortune to their descendants. If [you] do not do so, there will be misfortune.

Even when you prepare sacrificial rites for other people [not your own family] or prepare offerings for friends of your husband [or father-in-law], do so as if they were for [the ancestors of] your own family. If you make offerings in an impure manner, please take care, for it will harm the virtue of your heart-mind and damage the good fortune [of you and your family].

Acknowledgments

This essay is developed from my previous research on Song Siyeol and rituals on women. I would like to express my gratitude to anonymous reviewers for the Journal of Confucian Philosophy and Culture for their constructive comments and suggestions. Special thanks to Philip J. Ivanhoe for thorough and careful reading and comments.

References

- Bae, Sanghyeon 배상현. 1996. Joseon jo Giho hakpa ui yehak sasang e gwanhan yeongu 조선조 기호학파의 예학사상에 관한 연구 (A Study on Ritual Thoughts of Giho School in Joseon). Seoul: Research Institute of Korean Studies, Korea University.

- Choe, Yeongseong 최영성. 2007. “Myeongjae Yun Jeung gwa Myeongchon Na Yangjwa” 명재 윤증과 명촌 나양좌 (明齋 尹拯과 明村 羅良佐) (Myeongjae Yun Jeung and Myeongchon Na Yang-jwa). Yuhak yeongu 유학연구 (Studies in Confucianism) 15: 77-100.

- Complete Works of Master Sagye 沙溪先生全書 (Sagye seonsaeng jeonseo). Accessed January 27, 2021. In Korean Literary Collection in Classical Chinese. http://db.mkstudy.com/, .

-

Deuchler, Martina. 1992. The Confucian Transformation of Korea: A Study of Society and Ideology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

[https://doi.org/10.1163/9781684170159_002]

- Do, Minjae 도민재. 2003. “Yugyo gwallye ui sahoe jeok uimi” 유교 관례의 사회적 의미 (Societal Meaning of Confucian Mapping Rite). Yugyo munhwa yeongu 유교문화연구 (Journal of Confucian Culture) 6: 105-24.

-

Ebrey, Patricia B. 1991. Confucianism and Family Rituals in Imperial China: A Social History of Writing About Rites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400862351]

- Gwak, Jongseok 郭鍾錫. n.d. Myeonu jip 俛宇集 (Collected Works of Myeonu). Accessed March 1, 2021. http://db.itkc.or.kr/, .

- Ha, Yeonghwi, et al. n.d. Yet pyeonji nanmal sajeon 옛 편지 낱말사전 (Dictionary for Old Korean Letters DB). Accessed on February 23, 2021. http://waks.aks.ac.kr/, .

- Heo, Raguem 허라금. 2002. “Yugyo ui ye wa yeoseong” 유교의 예와 여성 (Confucian Li and Women). Sidae wa cheolhak 시대와 철학 (Journal of Philosophical Thought in Korea) 13 (1): 323-52.

- Hong, Insuk 홍인숙. 1993. “17-segi yeoseongsa ui munje jeok inmul, Uam Song Siyeol: Bijiryu, jemun gwa Uam Seonsaeng Gyenyeoseo reul jungshim euro” 17세기 여성사의 문제적 인물, 尤庵 宋時烈: 碑誌類, 祭文과 〈우암선생계녀서〉를 중심으로 (The Problematic Figure in the Seventeenth-Century History of Women, Uam Song Siyeol: Focusing on Inscriptions, Sacrificial Writings, and Instruction to My Daughter). Dongyang gojeon yeongu 동양고전연구 (Study of the Eastern Classic) 18: 132-34.

- Jo, Hyeong-won 조형원. n.d. Hwayang yeonwonnok 華陽淵源錄 (Records of the Origin of the School of Hwayang). Version held at National Library of Korea. Accessed March 1, 2021. http://www.nl.go.kr, .

- Joseon wangjo sillok 朝鮮王朝實錄 (Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty). 2005. Gwacheon: National Institute of Korean History. Accessed March 1, 2021. http://sillok.history.go.kr, .

- Li Xueqin, et al. 2000. Shisanjing zhushu zhengliben 十三經注疏(整理本) (Commentaries and Sub-commentaries on the Thirteen Classics). 1st ed. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe.

- Liji zhushu 禮記注疏 (Commentaries on the Book of Rites). SKQS ed. Accessed March 1, 2021. http://Ctext.org, .

- Mencius. Accessed March 1, 2021. http://Ctext.org, .

- Siku quanshu 四庫全書 (Library of the Four Treasuries). n.d. Wenyange edition. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong & Digital Heritage Publishing. CD-ROMs.

- Sima, Guang 司馬光. n.d. Shuyi 書儀 (The Letters and Etiquette). SKQS ed.

- Sohn, Jik-Soo 손직수. 1981. “Joseon sidae yeseong gyohunseo e gwanhan yeongu” 조선시대 여성교훈서에 관한 연구 (A Study on Books Concerning Women’s Education in the Joseon Dynasty). PhD diss., Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul.

- Song, Siyeol 송시열. 1986. Uam seonsaeng gyenyeoseo 우암선생 계녀서 (Admonishments for Women by Uam). Translated by Anonymous. Seoul: Cheongeumsa.

- Song, Siyeol 송시열. (1732) 2013a. Songja daejeon 宋子大全 (Great Compendium of Master Song), 259 vols. Hanguk munjip chonggan 한국문집총간 (Comprehensive Publication of Korean Literary Collections in Classical Chinese), vols. 108-116. Seoul: Hanguk gojeon beonyeogwon. First published in 1901. Accessed March 1, 2021. http://db/itkc.or.kr.

- Song, Siyeol 송시열. (1732) 2013b. Songja daejeon burok 宋子大全附錄 (Additions to Great Compendium of Master Song). 19 vols. Reprint, Seoul: Institute for the Korean Classics. Accessed March 1, 2021. http://db/itkc.or.kr.

- Veritable Records of King Gyeongjong 景宗實錄 (Gyeongjong sillok), 15 vols. See the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty.

- Veritable Records of King Sukjong 肅宗實錄 (Sukjong sillok), 65 vols. See the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty.

- Veritable Records of King Yeongjo 英祖實錄 (Yeongjo sillok), 127 vols. See Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty.

- Witt, Charlotte, and Lisa Shapiro. 2020. “Feminist History of Philosophy.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter), edited by Edward N. Zalta. Accessed April 10, 2021. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/feminism-femhist/, .

- Yang, Jihye 양지혜. 1998. “Gyenyeogaryu gyubanggasa ui hyeongseong e gwanhan yeongu” 계녀가류 규방가사의 형성에 관한 연구 (A Study on the Formation of Gyenyogaryu Gyubanggasa). Seoul: Ewha Womans University Press.

- Yao, Xinzhong. 2003. RoutledgeCurzon Encyclopedia of Confucianism. London: Routledge.

- Yi, Eun-young 이은영. 2006. “Chuksa wa jaseol eul tonghae bon gwallye: 17 segi yangsang eul jungsim euro” 祝辭와 字說을 통해 본 冠禮: 17세기 양상을 중심으로 (Confucian Coming-of-Age Ceremony Attested in Congratulatory Addresses and Alias Explanations: Centering on the Social Customs Used in the Seventeenth Century). Jeongsin munhwa yeongu 정신문화연구 (Research on Korean Studies) 29 (2): 67-98.

- Yi, Hwang 이황. n.d. Toegye jip 退溪集 (Collected Works of Toegye). Accessed March 1, 2021. http://db.itkc.or.kr/, .

- Yi, Mun-ju 이문주. 2002. “Seonginsik euroseoui gwallye ui gujowa uimi bunseok” 성인식으로서의 관례의 구조와 의미분석 (Structure and Meaning of Capping Rite as an Initiation Ceremony). Yugyo sasang munhwa yeongu 유교사상문화연구 (Study on Confucian Thought and Culture) 17: 25-50.

- Yi, Uijo 이의조. 2011. Gugyeok garye jeunghae 국역 가례증해 (Korean Translation of the Extended Interpretations to the Family Rituals), 6 vols., edited by Korean Classical Ritual Research Society. Seoul: Minsogwon.

- Yi, Yeon-suk 이연숙. 2002. “Uam hakpa yeongu” 우암학파연구 (A Study on the Uam School). PhD diss., Chungnam National University.

- Zheng, Xuan 鄭玄, and Jia Gongyan 賈公彦. (n.d.) 1999. Yili zhushu 儀禮註疏 (Commentaries to the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonies). Vol. 5 of Shisanjing zhushu. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe.

- Zheng, Xuan 鄭玄, and Kong Yingda 孔穎達. (n.d.) 1999. Liji zhengyi 禮記正義 (Corrected meaning of the Book of Rites). Vol. 6 of Shisanjing zhushu zhengliben.

- Zhu Xi 朱熹. n.d. Jiali 家禮 (Family Rituals). 5 vols. SKQS ed.

- Zhu Xi 朱熹. n.d. Zhuzi yulei 朱子語類 (Classified Sayings of Master Ju). SKQS ed.

- Zhu Xi 朱熹, and Chen Xuan 陳選. n.d. Xiaoxue jizhu 小學集注 (Collected Commentaries on the Elementary Learning). SKQS ed.

- Zhu Xi 朱熹, and Patricia B. Ebrey. 1991. Chu Hsi’s Family Rituals: A Twelfth-century Chinese Manual for the Performance of Cappings, Weddings, Funerals, and Ancestral Rites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Zito, Angela. 1997. Of Body and Brush: Grand Sacrifice as Text/Performance in Eighteenth-century China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.