Gratitude Without a Self

© Institute of Confucian Philosophy and Culture, 2023

Abstract

Gratitude plays a critical role in our social lives. It helps to build and strengthen relationships, and it enhances wellbeing. Gratitude is typically thought of as involving oneself having a positive feeling towards another self. But this kind of self-to-self gratitude seems to be at odds with the central Buddhist view that there is no self. Feeling gratitude to someone for some past generosity seems misplaced since there is no continuing self who both performed the generous action and is now the recipient of gratitude. In this paper, we explore how the Buddhist might respond to this problem. In response, Buddhists characterize a kind of gratitude (anumodanā) that is not fully propositional, but nor is it a notion that critically implicates the problematic concept of self. Anumodanā (literally rejoicing in good deeds of another) is best thought of as an expression of sympathetic joy (mudita) which is classified among the “sublime abidings” or “perfections” in Buddhism. In this paper we explain the notion of anumodanā and its functioning in the context of dāna (gift-giving or almsgiving in the Buddhist monastic context) to explain how it recovers some of the benefits of our ordinary reactive attitude of gratitude without implicating the self.

Keywords:

Reactive attitudes, gratitude, no self, anumodanā, dāna, revisionismI. Introduction

Social emotions like gratitude and guilt play a vital role in our everyday lives. These emotions are woven into the fabric of our social lives to such an extent that it is hard to see how we could do without them. However, powerful philosophical arguments seem to call into question the theoretical presuppositions behind some of these emotions. In the contemporary literature in Western philosophy, this issue has been most extensively explored in the context of free will skepticism. If people don’t have free will, then it seems mistaken to think that anyone deserves gratitude, or that anyone should feel guilty for their actions. After all, if people don’t have free will, then they don’t deserve credit for their behaviors whether they are good or bad.

Buddhism poses a related problem for these kinds of emotions. A central thesis of Buddhist philosophy is that there is no self. As a result, on this view, it makes little sense to feel guilty for a past action, since such a feeling seems to presuppose that the person feeling guilty is the same as the person who committed the infraction. However, if there is no self, how is this possible? Similarly, feeling gratitude to someone for some past generosity seems misplaced since there is no continuing self who both performed the generous action and is now the recipient of gratitude. In this paper, we will explore how the Buddhist might respond to these kinds of problems, focusing on the issue of gratitude without a self.1

It’s instructive to consider how free will skeptics have dealt with social emotions like guilt and gratitude. The contemporary discussion is typically framed against Strawson’s famous paper, “Freedom and Resentment.” In that paper, Strawson maintained (among other things) that our lives would be greatly diminished if we uprooted reactive attitudes like resentment, anger, and gratitude. Thus, he maintains, if the denial of free will is supposed to carry with it the rejection of these attitudes, denying free will carries an enormous cost. Hard incompatibilists, who maintain that we lack free will, have tried to assuage these worries (e.g. Pereboom 2001, 2007; Sommers 2007; Waller 1990). Derk Pereboom has developed the most systematic response on behalf of the hard incompatibilist. Part of his response is that many of the reactive attitudes, e.g., love, are largely unscathed by the denial of free will (Pereboom 2007, 121–2; see also 2007, 11–13). He acknowledges though that some reactive attitudes really are seriously threatened by hard incompatibilism. Pereboom writes, “Moral resentment, indignation, and guilt would likely be irrational for a hard incompatibilist, since these attitudes would have presuppositions believed to be false” (Pereboom 2007, 122; also Sommers 2007, 15). For those problematic attitudes, Pereboom has two possible replies. He claims that either the targeted attitudes aren’t necessary for good interpersonal lives or there are analogues that can serve in their stead (Pereboom 2007, 122).

Like hard incompatibilism, Buddhism maintains that some of our commonsense metaphysical beliefs are mistaken. For our purposes, the important metaphysical belief challenged by Buddhism is the belief in a self. According to Buddhism, the idea that there is a self is a false presupposition. Just as with the belief in free will, the belief in a self seems to underlie many of our practices. Hence, the Buddhist must also face the implications of the no self view for our lives. Should we extirpate the belief in the self? Here, Buddhism provides substantive guidance. The primary practical goal of Buddhism is to reduce suffering. Indeed, the goal of reducing suffering is the heart of Buddhist soteriology. And Buddhists maintain that the most basic source of suffering is the false metaphysical presupposition that there is a continuing self. As a result, Buddhism is broadly committed to uprooting the belief in self. But how would this impact our lives?

When considering the implications of Buddhism for the reactive attitudes, one must consider a range of questions that will include (1) whether the reactive attitude depends on an invocation of the self, and (2) whether the reactive attitude contributes to suffering. The results of this inquiry will indicate the kind of changes that would be recommended by Buddhist Revisionism. In addition to questions about what Buddhism itself entails about Revisionism, however, we need to consider broader questions about the implication of the Buddhist revolution. We can think of this as a Strawsonian question. In the context of the potential threat of determinism, Strawson maintained that whether it’s rational to retain the reactive attitudes if determinism is true, “we could choose rationally only in the light of an assessment of the gains and losses to human life, its enrichment or impoverishment” (1962, 83). We think a similar issue arises in the context of Buddhism. If we are to determine whether it is rational to retain the reactive attitudes if Buddhist metaphysics and soteriology is correct, we must consider the gains and losses to human life of Buddhist Revisionism.

II. The Psychological Account of Gratitude

A central aim of our paper is to argue that many of the benefits of gratitude can be preserved consistently with adopting the no self view. But this aim presupposes that there are important benefits to gratitude. In this section, we describe some of the key benefits of gratitude, drawing on contemporary work in philosophy and psychology.

Gratitude is a response of thankfulness that arises when one has received a benefit. It is typically associated with positive terms: as a prosocial emotion, a form of “social glue,” as a moral virtue and so on. Contemporary philosophers and psychologists agree that gratitude is a good thing that should be promoted. Psychologists have focused on examining the role of gratitude in promoting wellbeing and fostering good relationships and prosocial behaviour. Contemporary philosophers agree that gratitude can be thought of as a relationship enhancer. Swinburne, for example thinks that a genuine act of benevolence is thought to signal a desire or intention to start or to deepen a friendship (and gratitude as a response to the benevolence is the reciprocation of this intention, which enhances the relationship) (1989, 65). Blustein writes that while gratitude does not presuppose a pre-existing personal relationship, “it establishes one by some form of reciprocation” (1982, 190). Contemporary philosophers, however, are also interested in figuring out the conceptual nature of gratitude: is it an emotion or a disposition (a trait)? Is it an interpersonal emotion directed at agents who have bestowed a benefit to one in the past or can we think of it more generally in impersonal terms? This last question is of special interest here to us, especially in the light of the Buddhist no self view.

A. Propositional and Prepositional Gratitude

Philosophers concerned with analysing gratitude begin with cases in which we naturally express gratitude. Although it is natural to use gratitude terms in cases where we are grateful to a person or an agent, we sometimes use gratitude terms more impersonally. One can be grateful for the beautiful weather for one’s wedding day or natural beauty more generally. This latter sense of gratitude is called propositional gratitude, which is best understood as a proper response to a good state of affairs: X is grateful that p. But many, perhaps most, common uses of gratitude are of the interpersonal kind like being “grateful to someone for trying to help me;”, or “grateful to someone who stood up for me.” This triadic sense is called prepositional gratitude: X is grateful to Y for ϕ-ing. Contemporary philosophical literature focuses on prepositional gratitude as gratitude proper, the cases of propositional gratitude are taken to be expressions of appreciation rather than gratitude (Manela 2021 SEP). in the restrictions on the English word “gratitude,” particularly. But we do think the distinction between propositional and prepositional gratitude is important, and that it is certainly an important distinction when it comes to Buddhist accounts of gratitude.

B. Gratitude: Input, Output, and Function

Psychological accounts of emotions are typically given in terms of inputs, outputs, phenomenology, and the function of the emotion (see, e.g., Keltner and Lerner 2010). Thus, fear is thought to be an emotion that is activated by an input that constitutes a perception of imminent threat, and it generates as output an action tendency to escape the situation. The phenomenology has a negative valence. And the function of fear is widely regarded as that of protecting the organism from immediate, concrete dangers. The input-output profile of fear makes sense given the function. A system that has the function of protecting the organism from danger needs to be activated by threats and motivate protective responses.

In the case of gratitude, the characteristic input is a perception that someone has intentionally benefited the agent.2 The benefit is typically something that the agent is happy to have. The characteristic output of gratitude is an action tendency to behave generously towards the benefactor.3 This generosity is often a kind of reciprocal response. The phenomenology of gratitude has a positive valence, and experimental participants have characterized the feeling variously as joy, release, and comfort (Elfers and Hlava 2016).

The foregoing account of the input/output profile of gratitude is naturally thought of as an account of prepositional rather than propositional gratitude. Perhaps the best known account of the function of such gratitude derives from classic work by Robert Trivers on reciprocal altruism. Trivers maintains that much altruistic behavior in the animal kingdom seems puzzling from an evolutionary point of view until we recognize that often when one individual behaves altruistically towards another, the recipient will return the favor. Trivers suggests that this can, among other things, provide an account of the human emotion of gratitude. He writes, “I suggest that the emotion of gratitude has been selected to regulate human response to altruistic acts” (Trivers 1971, 49). If someone benefits you, and you return the favor, this increases the chances that these positive exchanges will continue. Hence the reciprocity of reciprocal altruism. Sara Algoe has developed an influential account of the function of gratitude, grounded in the same kinds of considerations as Trivers. She dubs it the “find, remind, and bind” account. On this account, gratitude involves identifying a high-quality relationship partner, and the generous response serves to improve the relationship: that is, gratitude finds new or reminds of a known good relationship partner and helps to bind recipient and benefactor closer together (Algoe 2012, 457). Thus, the function of gratitude on this account is to maintain or strengthen a relationship with a thoughtful/considerate partner. These dyads might be siblings, parent-child, friends, romantic partners, and even co-authors.

This binding function makes sense of the input/output profile of gratitude. Individuals who intentionally benefit you are the kinds of individuals with whom it is advantageous to sustain a relationship and behaving beneficially towards them will encourage and sustain the relationship. The binding function also makes sense of the phenomenology of gratitude. Building and sustaining a beneficial relationship is an apt occasion for positive feelings of joy and comfort.

We will assume in what follows that something along the lines of the Trivers/Algoe view of the function of gratitude is correct. In particular, we will assume that a primary function of gratitude is to sustain or strengthen a relationship that is valuable to the recipient. Insofar as gratitude motivates the beneficiary to be generous towards the benefactor, gratitude in the benefactor plausibly generates a cycle of beneficial reciprocal responses.

C. Additional Beneficial Effects of Gratitude

Even if the primary function of gratitude is in terms of relationships between individuals, that doesn’t preclude the possibility that gratitude also has effects that go beyond the confines of relationship benefits. Indeed, psychologists have identified several ways in which gratitude has effects that go beyond benefits between benefactor and beneficiary.

Gratitude, as we’ve seen, motivates the beneficiary to behave generously towards the benefactor. But gratitude also seems to motivate the beneficiary to behave generously towards people other than the benefactor. Behavioral experiments demonstrate that gratitude fosters prosocial behaviour (Carlson et al. 1988; Emmons and McCullough 2004; Bartlett and DeSteno 2006). For instance, when participants receive a benefit in an economic game but they are unable to reciprocate the benefit to their benefactor, they will often act so as to benefit another player (Dufwenberg et al. 2001).

There are competing explanations for why beneficiaries might extend benefits to people other than their benefactor. One explanation is that it is a kind of mistake4 Another possibility, though, is that such behavior reflects a kind of “upstream reciprocity” (or “pay it forward” reciprocity) that might have evolutionary advantages in facilitating cooperation (Nowak and Roch 2006). If the latter theory is right, this might constitute a reason to think that, in addition to the binding function, gratitude also has the function of generating prosocial behavior. Either way, though, it’s plausible that feelings of gratitude are elevating, and a consequence of this is prosocial action.

Displays of gratitude towards a benefactor plausibly increase the likelihood of further generosity by the benefactor. This might be a kind of subsidiary function of reciprocal altruism. Part of what makes gratitude advantageous is that it makes the benefactor more likely to produce more benefits for the original beneficiary. However, the reinforcement of generosity plausibly has more general effects on benefactors. McCullough and colleagues elaborate on this point:

When a beneficiary expresses gratitude, either by saying "thank you" or providing some other acknowledgment of appreciation, the benefactor is reinforced for his or her benevolence. Thus, the benefactor becomes more likely to enact such benevolent behaviors in the future. (2001, 253)

The basic idea here is a simple application of something like reinforcement learning. Getting positive responses to one’s generosity makes being generous more appealing.

D. Psychological Benefits

Several studies have indicated that gratitude is associated with a variety of psychological and health benefits5 For instance, one study pinpointed gratitude as a protective factor against Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Israel-Cohen et al. 2015). To give the flavor of some of this research, consider a study by Emmons and McCullough (2003). They had participants create lists before bed. In one condition (the control condition), the list was just events from the week, but in another condition, participants were told to list things they were grateful for. The instructions for the gratitude condition read as follows:

There are many things in our lives, both large and small, that we might be grateful about. Think back over the past week and write down on the lines below up to five things in your life that you are grateful or thankful for. (379)

Emmons and McCullough report the following examples drawn from the lists made by participants: “waking up this morning,” “the generosity of friends,” “for wonderful parents,” “to the Rolling Stones.” They found that participants in the gratitude condition had higher self-reported wellbeing (381). In another study, they found that participants in the gratitude condition reported more and better sleep than participants in the control condition.6

E. Costs of Ingratitude

Thus, gratitude seems to have a wide range of positive impacts, both for moral behavior and general psychological wellbeing. However, it’s also important to consider the costs of being ungrateful. In early modern philosophy, ingratitude was often used as a paradigm example of morally bad behavior. Hume, for instance, writes, “Of all crimes that human creatures are capable of committing, the most horrid and unnatural is ingratitude, especially when it is committed against parents” ([1739] 1969, 16). To be sure, we find it disheartening when our acts of generosity is greeted with ill will. Even the absence of gratitude can be upsetting. Imagine a colleague has inadvertently created a problem that will lead her to be sanctioned and you solve the problem while she watches. She will likely say that she is grateful to you for solving the problem. However, if her response is merely a casual acknowledgment of the situation, such as stating, "I'm glad the problem is resolved," you would likely find this somewhat annoying.

The psychological research confirms the intuition that ingratitude is aversive. To take one example from the experimental literature, Suls and colleagues (1981) had grade school and college students read four vignettes with two characters. The first character either helped or didn’t help the second, and subsequently the second either helped or didn’t help the first. Thus, the vignettes had this structure:

- i. A helps B then B helps A;

- ii. A helps B then B doesn’t help A;

- iii. A doesn’t help B then B doesn’t help A;

- iv. A doesn’t help then B helps.

B is judged more negatively in the ingrate condition (ii) than in all the others. Indeed, for the older children and college students, B was judged much more negatively in the ingrate condition (1981, 28). Such ingratitude plausibly has negative consequences—making it less likely that a benefactor will engage in the kind of behavior that was followed by ingratitude (e.g., McCullough et al. 2001, 253). This might then work against the kind of cooperation and moral reinforcement that seems to be facilitated by gratitude.

Thus, gratitude has a wide range of benefits, some directly tied to the function of sustaining and strengthening relationships between benefactor and beneficiary, some more indirect benefits for upstream reciprocity and moral reinforcement, and some very general benefits to wellbeing. Ingratitude, by contrast, is aversive, and threatens to undermine the benefits that gratitude facilitates. Given the benefits of gratitude it should be amply clear that it is a valuable interpersonal emotion. Buddhists agree with contemporary philosophers and psychologists that gratitude should be preserved and cherished.

III. Gratitude and No Self

In section II-A we distinguished between propositional and prepositional gratitude. Propositional gratitude is gratitude for a state of affairs, like being grateful for a beautiful sunset. Propositional gratitude is associated with positive effects. Indeed, when asked to list things for which they were grateful, participants will often list states of affairs. One of the examples above illustrates this where a participant expressed gratitude for “waking up this morning.” This kind of gratitude does not essentially involve any representation of the self. It doesn’t have the interpersonal characteristic of prepositional gratitude. As a result, the Buddhist can happily acknowledge and accept a role for propositional gratitude. Indeed, there are a lot of gratitude practices that would be considered propositional. Buddhist monks in the Thai Forest tradition who live in Australia report that their regular practices include being grateful that they live in a country with free healthcare. This is a good thing since propositional gratitude has significant positive value. With prepositional gratitude, it’s a different story. Given that propositional gratitude is consistent with the no self view, we will focus our discussion on the more difficult kind of gratitude—prepositional.

A. Prepositional Gratitude as Inconsistent with No Self View

While the propositional sense of gratitude seems prima facie consistent with the no self view, that is not the case for the prepositional sense. To see why, consider Strawson’s characterisation of gratitude as one of the positive interpersonal reactive attitudes, as opposed to negative emotions such as resentment and anger. He says,

If someone’s actions help me to some benefit I desire, then I am benefited in any case; but if he intended them so to benefit me because of his general goodwill towards me, I shall reasonably feel a gratitude which I should not feel at all if the benefit was an incidental consequence, unintended or even regretted by him, of some plan of action with a different aim. ([1962] 2008, 22)

Buddhists would be uneasy with gratitude as Strawson characterizes it because the characterization is loaded with reference to oneself and another. Such reference to the self seems to be at odds with the no self view. It reveals that gratitude presupposes a self. Buddhists seem pressed to resist this prepositional characterisation because it brings to the fore that this valuable emotion involves an implicit commitment to the self. Indeed, this might also be called self-to-self gratitude. Prepositional gratitude presupposes a self, in a way that propositional doesn’t. However, propositional gratitude does not seem to carry the function of gratitude as a relationship enhancer.

Note that the situation here for the Buddhist is rather different than for the hard incompatibilist. The hard incompatibilist who rejects free will but retains the commitment to self, can still keep a robust commitment to gratitude in the prepositional sense. This is reflected in Pereboom’s discussion. He writes, “gratitude includes an element of thankfulness toward those who have benefited us. Sometimes, being thankful involves the belief that the object of one’s attitude is praiseworthy for some action. But one can also be thankful to a pet or a small child for some favor, even if one does not believe that he is morally responsible” (Pereboom 2001, 201). The Buddhist cannot make this move so easily. How then might the Buddhist resolve the apparent tension between the commitment to no self and preserving and indeed encouraging gratitude practices? To address this, we focus on the Abhidharma Buddhist tradition and its unique typology of mental states and their account of emotions before we turn to gratitude.

B. Abhidharma Model of Mind

In order to understand Buddhist treatments of emotions, we need to have in place a richer sense of Buddhist philosophy of mind and, in particular, the basis for their distinctions between different mental factors. The Buddhist analysis of experience maintains that what we experience as a temporally extended, uninterrupted flow of phenomena is, in fact, a rapidly occurring sequence of causally connected events, each with its particular discrete object. To explicate this, Buddhist philosophers decompose the world and us in it into a causal sequence of evanescent mental and physical states (nāmārūpa). Though there are various construals of this central Buddhist nāmārūpa in the literature, the best way to understand this notion is that of a mindedbody (Ganeri 2017, 77–79). In Abhidharma Buddhism, the mindedbody is further analyzed into “dharmas,” which are discrete momentary factors. Importantly, the dharmas include both physical and mental factors. On the Abhidharma picture, mind is not a substance or central processor that produces experiences and thoughts; rather it is an aggregate of many simultaneous series of mental dharmas. These mental dharmas are best thought of as “phenomenologically basic” features that constitute conscious experience (Dreyfus 2011). This does not, however, mean that the phenomenological features are readily available in ordinary introspection. The claim is that mental dharmas are in principle available in first-person experience, though discerning the dharmas requires meditation practice. Indeed, some dharmas are better thought of as subliminal mental factors that can be brought to the surface only through sustained meditation practice. The Abhidharma schools disagree about the number, classification, and role of these features in experience. So the Abhidharma philosophers take great pains to provide ever new lists and classifications of mental dharmas and detailed arguments to justify the proposed revision. However, Abhidharma schools agree on the starting point for grouping the mental factors: They are primarily classified as good (kusala), bad (akusala), and neutral (abyākata). Good (kusala) is defined as that which is “salutary, blameless, skillful” (Atthasālinī, 62–63) and thus reduces suffering. Bad (akusala) is just the opposite; it is unhelpful, blameworthy, unskillful and augments suffering. Certain mental factors inherently possess a wholesome or positive nature, such as compassion, wisdom, and the like. Conversely, some factors are inherently unwholesome or negative, like anger, greed, and craving. There also exist neutral factors, such as equanimity and resolve. The moral valence of a given conscious state or thought, whether it is good or bad, is determined by the moral valence of mental factors constituting conscious thought and experience. For example, a thought associated with compassion would be good because compassion is a good factor; a thought associated with equanimity would be indifferent because equanimity is disinterested; a thought associated with greed and ignorance would be bad because greed and ignorance are bad factors.

The overarching aim of the Abhidharma philosophy is to cultivate the wholesome mental factors and eradicate the unwholesome ones. This, in turn, will ensure a prevalence of good thoughts, intentions, and actions, thereby reducing suffering. How does one go about identifying the good and the bad factors? The Abhidharma answer is to turn to the tradition as a repository of moral knowledge delineating the good and bad factors. However, experienced teachers also suggest a turn to moral phenomenology. The idea is to pay attention to how thoughts or actions appear or feel to a person. In developing their moral phenomenology, Buddhists begin by noticing that the pursuit of sense pleasures is typically mixed with hardship and disturbances in the mind because such pursuits involve greed and craving for more of the same. In contrast, by purifying the mind through restraining oneself from indulging in sense pleasures, one “experiences internally an unmixed ease (sukha)” (Majjhima Nikaya I, as translated in Nanamoli and Bodhi 1995, 181). For example, by their very presence in the mind, lovingkindness and compassion have a calming influence and result in easing the mind. Good and bad thoughts and actions can both appear joyful and pleasurable, but only bad thoughts cause distress and disturb the mind. In the Abhidharma psychology, good or wholesome (kusala) thoughts are never painful or distressing, though they can be neutral. They are felt as neutral when they are experienced through equanimity and disinterest. The thought is that we focus on experientially available distinctions to figure out which mental factors are wholesome or good. Wholesome factors can be differentiated from unwholesome ones in that the former involve a healthy and uplifting state of mind in contrast to the latter that distress and disturb the mind.

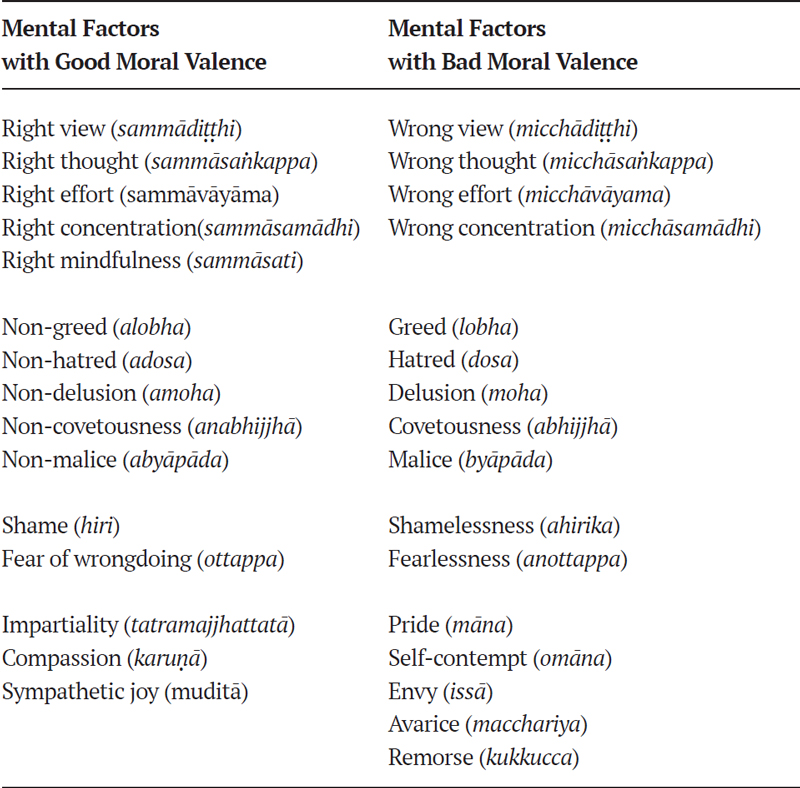

Given the salient differences between the Abhidharma model of the mind and other models of mind in Western philosophy and psychology, it is natural to expect that the mental categories will be very different. The Abhidharma philosophers are not concerned with distinguishing emotions from other mental factors. They are, like contemporary emotion theorists, interested in the action-guiding role of particular emotions; but it bears emphasis that these actions are set in the context of the guiding principle of reducing suffering in the world. Thus, the primary division among mental factors will be in terms of whether they reduce suffering (good) or increase suffering (bad) or have no effect on suffering (neutral). Ignoring the neutral factors for now, a partial list of good and bad factors is reflected in figure 1 to give the reader a sense of the Abhidharma typology.

C. Buddhist Account of Kṛtajña Gratitude

Given the basic division in Buddhist typology between good and bad factors, where can we place gratitude or kṛtajña? Kṛtajña does not feature as one of the basic positive mental factors worth cultivating. But kṛtajña, literally translated kṛta (what is done) and jña (who knows); in other words, “being mindful of what has been done.” Therefore, it is best thought of as a complex attitude derived from the basic wholesome factor of “right mindfulness.” Kṛtajña can be conceived of as a complex attitude that remembers the good things that have been done and keeps them in mind. It is used for acknowledging past benefits and being mindful of favours. The example usually given to illustrate kṛtajña in the Nikāyas is that of an old jackal who howls at the break of dawn to acknowledge the gift of a new day. The jackal story might suggest that the Buddhists are thinking about gratitude in a propositional sense. No one is being thanked here, the jackal is grateful that it is a new day. The use of examples involving the jackal from the Nikāyas suggests that gratitude does not seem to invoke the problematic reference to the self. This, however, is not the whole story.

In the famous Jātaka tales, gratitude is often used in a way that does implicate the self. For a bit of context, the Jātaka tales mainly concern the previous births of the Buddha in both human and animal form. In these stories, the Buddha may appear as a king or as a lowly animal—however, regardless of the form in which the Buddha manifests, he consistently embodies Buddhist virtues, such as generosity and compassion. Consider the Sīlavanāga Jātaka (No. 72; as found in Appelton 2010), a magnificent white elephant “adorned with the ten perfections” is contrasted with a wicked person. According to the tale, a certain person is lost in wilderness. He is starving but is unable to find his way home. The person meets an elephant who saves his life by bringing him back to the human habitat. Far from being grateful, however, the greedy man goes straight to the ivory-workers’ quarters and asks them how much they will pay for the tusks of a living elephant. He then returns to the elephant three times in a row—first sawing off the elephant’s tusks, then removing the stumps of the tusks, then gouging into the flesh itself to retrieve every last ounce of ivory, with each gift being freely offered up by the compassionate elephant. As we might expect, the kind and compassionate elephant serves as an effective foil for the wickedness of the man. The moral of the story is to encourage people to develop the ten perfections and give up their wicked ways. If non-rational animals can be compassionate, why can’t rational human beings be so too?

Setting aside the moral of the story, the important thing to notice is that the right response to receiving the said benefit is that the person should be extremely grateful to the benefactor (the elephant) for saving his life. The ingrate is blameworthy. In the early Nikāyas, the Buddha is reported to have said, “Endowed with four things a foolish, unskilled and wicked person is one who has destroyed his own foundation, is censurable and blameable by the wise, and accumulates a lot of demerits. With what four? With bodily misconduct, with verbal misconduct, with mental misconduct, and with ingratitude and not helping in return” (Aṅguttara Nikāya 4.223, emphasis added) The Sīlavanāga Jātaka construes gratitude (kṛtajña) in interpersonal sense, after all it is the (with the ten perfections) is a human appearing in the elephant form. It is clear that this Jātaka tale invokes gratitude in the prepositional sense: the beneficiary is expected to be grateful to the benefactor (in the form of an elephant) for helping him to return home. But this sense of gratitude seems to be at odds with the no self view. Both the beneficiary and the benefactor are conceived of as continuing agents, the beneficiary is expected to be grateful to the benefactor for a favour bestowed in the past. So, it seems that, like the English term gratitude, kṛtajña seems to allow for both propositional and prepositional readings. The prepositional reading of gratitude and its invocation of the self-spells trouble for the coherence of Buddhist view.

D. The Two Truths?

Perhaps the most obvious strategy for dealing with this apparent inconsistency is to appeal to the doctrine of two truths. Across a wide range of contexts, the doctrine of two truths is called upon to explain away the inconsistency between the no self view and frequent use of conventional terms like persons, Brahmin, Bhikkhu and even the first-person pronoun “I” by the Buddha himself in the scriptures. According to the Two Truths doctrine, while reference to a self cannot be ultimately true – since ultimately there is no self—a statement that talks about persons can be conventionally true provided acceptance of the statements reliably leads to successful worldly activities (Siderits 2008, 35).

According to most Buddhist philosophers, the implicit or explicit reference to the self in the Vinaya rules is best understood as referring to conventional persons. Dharmas alone are ultimately real but many things in our folk ontology, for example chariot and pots, are conventionally real. The idea here is that terms like “pot” stands for a concept that that has proven useful (for storage) for creatures like us given our interests and cognitive limitations. We are unable to keep track of many evanescent momentary dhammas. Pots and chariots are in this sense useful fictions that deserve a place in a sort of second-tier ontology (Siderits 2019, 315). Using exactly the same strategy, Siderits argues that given that there is no self and the dharmas that ultimately constitute a person are replaced many times in one life, what should we say of persons over a lifetime? As in the case of pots and chariots, we employ distinction between the two truths. The term “person” does not refer to anything at the level of ultimately real dharmas. But persons can refer to conventionally real, conceptual fictions that supervene on causal series of appropriately organized sets of dharmas. Persons are useful fictions because they can perform some of the work of selves: they can be conceived of as agents of action and bearers of responsibility which means our interpersonal practices of responibilty attribution will be left unscathed by the Buddhist rejection of the self.

Our concern with this strategy is that substituting person for self surreptitiously imports the idea of self into the argument. By introducing persons as convenient fictions we risk reintroducing self-interests and attachment to continuing persons. These attachments and interests are exactly the sorts of things that encourage the defilements of greed, hatred and the “I” delusion. And postulating more or less persisting persons will lead to the unwholesome emotional habits and biases that lead us to prioritise our personal futures (Williams 1998, 110-2; Chadha 2021). The only difference is that in the second-tier ontology the “I” refers to conventional persons rather than ultimately real selves.

Given this, in Section IV, we explore how the living Buddhist tradition finds an innvovative (if partial) solution to the proposed tension between gratitude and no self without reverting to the idea of persons. They introduce an analogue attitude for gratitude, anumodanā (literally rejoicing in good deeds by another) as a substitute for the problematic form of kṛtajña. Anumodanā, we contend, presents an innovative middle way solution by introducing an analogue attitude which preserves some of the valuable functions and benefits of gratitude without the presupposition of the self.

IV. Buddhist Revisionism

Thus, the Buddhist commitment to no self appears to conflict with the prepositional reading of gratitude or kṛtajña. In this sense gratitude is similar to self-conscious emotions like pride in that it also involves an insidious commitment to selves. In the case of gratitude, the problem seems even worse since both the beneficiary and the benefactor are individual selves. Consequently, we would expect gratitude in the prepositional or self-to-self sense to be in the category unwholesome or negative emotions that should be eliminated.

As we will see, Buddhists have a kind of systematic response to these concerns. Part of the response is theoretical. Buddhists characterize a kind of gratitude that is not fully propositional, but nor is it a notion that critically implicates the concept of self. In addition to the theoretical innovation, Buddhists have actually implemented practices that (partially) serve the functions of gratitude, and guard against the costs of ingratitude. This points to a significant difference between the Buddhist tradition and contemporary work on revisionism about free will. Buddhists have a history of communities that have attempted to implement revisions. Furthermore, these communities have survived, perhaps partly due to these revisions. The Buddhist community has norms and practices that seem to supply an alternative way of achieving the function of prepositional gratitude.

A. Costs of Rejecting Self-to-Self Gratitude

By rejecting the notion of self-to-self gratitude, Buddhists appear to forego the function and benefits associated with gratitude. One of the most significant benefits is the sustaining and strengthening of relationships that are mutually beneficial. The function of gratitude is tied to dyadic partial relationships, focusing on dyads like romantic partners and parent-child, etc; the Buddhist will be concerned because of their focus on “me,” “mine,” “my child.” The additional benefits, namely upstream reciprocity and moral reinforcement, are also something that the Buddhist values. Insofar as the Buddhist values generosity and compassion, downgrading gratitude as a negative emotion because it implicates the self is likely to be very costly. Add to that the cost of ingratitude, which is accompanied by aversive feelings, anger and resentment, all of which are negative states that the Buddhist wants to eliminate. The price of embracing the no self perspective and consequently rejecting gratitude seems too high.

B. The Buddhist Account of Anumodanā Gratitude

Kṛtajña or gratitude requires the supposition that the beneficiary is grateful to the benefactor for the benevolent act, and therefore the no self theory seems to undermine gratitude. However, to recover some of the benefits gratitude commonly has in interpersonal relationships, Buddhist traditions found a way around in the context of religious gift-giving (dāna). Dāna is best understood as ritually ordered sense of almsgiving to monks and the monastic community (saṅgha) more generally. Dāna is very important in the Buddhist context because the monasteries depend on gifts the laity for material support and perpetuating the monasteries is essential to perpetuating the Buddhist Dharma. Sustaining and maintaining this symbiotic relation and the cycle of beneficial reciprocal responses is crucial for the perpetuation of Dharma and survival of Buddhism (Berryman, Chadha, and Nichols 2023). The laity, in turn, rely on the monastics to teach the dharma. They also seek guidance from the monastics on moral and spiritual matters and expect the monastics to be available for performing important rituals in case of death, sickness, and other significant life events. Historically, the monasteries have benefitted from the belief among the laity that giving gifts (dāna) to the monks is likely to significantly enhance the positive karmic consequences achieved by the gift-giver.

The Buddhist tradition has devised an ingenious way of recovering the benefits of gratitude without the insidious reference to individual selves. Kṛtajña in the prepositional self-to-self sense sits uneasy with the no self view. For this reason, the Buddhists do not regard kṛtajña as a disposition associated with dāna—a verbal expression of thank you to the donor is not the appropriate response (Heim 2004, 68). In the Buddhist religious context, the right response of the recipient and the benefactor is anumodanā, literally rejoicing in good deeds of another. The recipient and the benefactor both express joy, and even a third parties observing the good act of giving rejoice with them. Anumodanā is best thought of as an expression of sympathetic joy (mudita) which is classified among the “sublime abidings” (or brahmavihāras, according to the Theravāda scholar and monk Buddhaghosa in his Visuddhimagga) and “Perfections” (or Pāramitās according to the Mahayana scholar and monk Nāgārjuna in his Dharmasaṃgraha). In what follows, we explain the notion of anumodanā and show how it functions in the Buddhist context to recover the benefits of gratitude.

C. The Dāna Ceremony

One might think that the reference to another in anumodanā is still loaded with reference to another self, the benefactor. To understand how the Buddhists avoid the insidious reference to the self, it is important to pay attention to the ritual of gift-giving. Buddhist monasteries organise occasional dāna ceremonies as an event in which the Buddhist community as a whole participates by celebrating the good act of giving. For example, Thai Buddhists believe that everyone that participates in the dāna ceremonies, not just the donor, accrues positive karmic merit.7 The dāna ceremony provides a model for a new way of thinking about gratitude.8 This is because rather than thinking of the gift as merely a benefit to an individual monk, the dāna is regarded as a benefit to the monastic community as a group. In return, the monastic community benefits the laity as a group. To take an example, living Buddhist societies in present day Thailand organise the annual Kathina ceremonies in which large groups of Buddhists band together for the ceremonial presentation of the robes to the monastery.9 The community folk band together with the donors and proceed to the monastery as a group to participate in the dāna ceremony. The entire Buddhist community contributes to the ceremonial event. The women prepare food, the men help carry the gifts, the men dance around the raised platform which is reserved for the monks. School children help carry the gifts to the monastery. These are expressions of anumodanā by the laity. The Buddhist text Suttasaṅgahaṭṭakatha describes anumodanā in the following way:

When people take joy (anumodanti) in [another’s] dāna, saying “this is good, this is great,” with clear minds and without envy or selfishness, or when there are those who [assist with another’s dāna] by rendering physical services, it is not the case that the gift is lessened or diminished by others taking pleasure or assisting in it. On the contrary, it is even more complete. Just as when one lamp is lit from another lamp, the light of the first lamp is not diminished, but instead the light of that lamp together with the single one increases, so too the gift is not diminished by this. Even those who just experience joy and render services are said to be sharers of the merit, that is, they receive a share of the merit. (As quoted in Heim 2004, 68)

The dāna ceremony supposedly benefits everyone (in the context of the Buddhist karma theory everyone gets a share of karmic merit). Indeed, even the beneficiary partakes in the ceremony by expressing anumodanā. But to be clear the beneficiary’s expression of anumodanā is not meant to be thank you to the donor, rather it is a response of joyful approval and acceptance. It is important to emphasize that anumodanā is an attitude towards the good act of giving. This revision would also be welcomed by the hard incompatibilist. Pereboom writes,

Gratitude involves an aspect of joy upon being benefited by another. But no feature of the hard incompatibilist position conflicts with one’s being joyful and expressing joy when people are especially considerate, generous, or courageous in one’s behalf. Such expressions of joy can produce the sense of mutual well-being and respect frequently brought about by gratitude. Moreover, when one expresses joy for what another person has done, one can do so with the intention of developing a human relationship. (2001, 202)

A Buddhist revisionist will be happy to endorse Pereboom’s point that the expressions of joy produce the sense of respect and mutual wellbeing, but the Buddhist will be concerned by the reference to persons and the intention of developing a human relationship between the benefactor and the beneficiary. Again, the sense of respect and the intention of developing a relationship is directed towards a particular beneficiary and thus brings back the insidious reference to the self.

D. Representatives Rather than Selves as Target of Anumodanā

To avoid the problematic reference to the self, the Buddhist suggests a further revision. Here the Buddhists draw on a general doctrine of a “worthy recipient” in the dāna practices in the broad religious context in South Asia. Hindus and Jains thought of dāna in a similar manner. In the Buddhist context, the gift (dāna) has to be commensurate with the “worthiness” of the beneficiary. The moral worth of the recipient is a primary consideration in how much benefit is produced from the dāna. One way in which Buddhist monastics are deemed to be worthy of the highest respect is that they receive dāna on behalf of the “universal saṅgha headed by the Buddha.” The Kathin ceremony in Thailand captures this sentiment by placing an image of the Lord Buddha on a gold-colored raised platform facing the laity. The senior monks are seated nearest to the Buddha image. The younger monks or novices sit further from the image. The robes, food, and other gifts is offered to individual monks seated on the platform. They receive the gifts as representatives of the saṅgha headed by the Buddha. The Buddha and thus the saṅgha is worthy of the highest respect. Another way in which Buddhist practices allow for individual monastics to demonstrate their worthiness is that beneficiaries can make a conscious effort to transform on account of receiving the gift, even if they are not yet worthy recipients. Rather than a verbal expression of kṛtajña or gratitude, individual beneficiaries qua representatives of the saṅgha acknowledge the favour by practicing harder to increase their moral worth, because of the background belief that the gains made by individual monks in their practice increases benefits for everyone. A second reason the moral worth of the recipient is important is that it produces the ideal response in the donor. The recipient is someone who is held in esteem and demands the highest respect (Śraddhā) from the benefactor. The moral value is determined by the objective qualities (for example, whether the monk is a novice or ordained, his dedication to practice, his spiritual achievements, and so forth) rather than subjective facts about the individual monk. This is to ensure that the benefit is bestowed impartially. What matters is not the individual beneficiary but what they represent. The result is a win for everyone: the benefits accrued by the lay community (including the donor) is massively increased and the spiritual status of the saṅgha is improved because the monk (qua representative of the universal saṅgha) achieves enlightenment. This provides a model for individual monastics qua representatives of the saṅgha to acknowledge the benefit. This possibility is flagged by stories in which monks practice harder, make more effort, after receiving the benefits. A story from the texts tells of a monk who receives dāna from a layman who, due to his unfortunate circumstances, must go to great personal sacrifice to give dāna. The monk acknowledges this by deciding to make the gift more beneficial by making himself more worthy. Since the reward for the donor is commensurate with the virtue of the recipient, the monk “deems it his duty, he who is the beneficiary, to increase the fruit by making himself greater” (Filliozat 1991, 241). The monk becomes more diligent in his practice and becomes enlightened. This story might seem to be suggesting that the beneficiary and the benefactor are trying to maximize benefit to each other. However, interpreting it in this manner is a mistake. The right attitude towards the act of dāna is anumodanā not kṛtajña. The efforts of the benefactor are justified because the beneficiary represents the saṅgha and the efforts of the beneficiary are justified because the benefactor is a representative of the laity. The efforts are meant to maximize benefits for everyone, conceived impersonally rather than the benefactor and the beneficiary conceived of as individual persons. It is worth emphasising again that anumodanā is an attitude towards the good act of giving, not towards a person.

The point here is that although the Buddhist account of dāna involves the benefactor and the beneficiary, as part of the dāna ceremony they are just representatives of groups, the laity, and the saṅgha. The notion of anumodanā thought of as participating in the joy of giving by the laity as well as the saṅgha allows for a novel expression of gratitude without smuggling in the self. Gratitude in the sense of anumodanā is an attitude towards an action of dāna. Though there are several participants in dāna ceremonies, they do not involve individual selves in a way that will conflict with the Buddhist no self doctrine. Giving and receiving benefits is impersonally conceived as altruistic actions aimed at alleviating suffering. This is accomplished through the laity offering dāna or benefits (food, robes, building material, labour, and so on) to the monastic community. In return, the monastic community acknowledges these offerings by intensifying their efforts and working harder to provide services such as teaching, conducting rituals during significant events, offering solace in times of illness and death, providing spiritual guidance, and so on.

E. Revising Expectations

We have shown how Buddhists have developed theoretical resources and community practices that help to serve some of the key functions of gratitude. It’s worth noting that these changes also plausibly change expectations in keyways that guard against feelings of ingratitude.

Ingratitude is aversive—we feel bad when another does not repay our generosity with gratitude. This alone makes ingratitude something Buddhists would want to minimize. It is clear that Buddhists despise ingratitude. The Sīlavanāga Jātaka tale (Section III-B) execrates the ingrate as wicked. In addition, ingratitude likely undercuts upstream reciprocity and moral reinforcement. This provides additional reason to guard against ingratitude. How does the Buddhist system manage this? Well, whether one feels ingratitude depends on one’s expectations. Non-Buddhist benefactors tend to expect displays of gratitude towards them from the beneficiary. But in important Buddhist contexts, this is not the expectation. As a result of being educated in the practices of ceremonial giving, donors know what to expect. Donors and the broader community of participants in the dāna ceremonies are aware that the offering is made to the universal saṅgha headed by the Buddha, rather than an individual monk. It is done with the highest respect without any expectation of gratitude towards the donor (either from the saṅgha or any other individual monk). The participation and the expression of joy (anumodanā) by the broader community, not just the individual donor, also makes clear that in giving a gift to the monastery, one does not expect to be singled out. Indeed, singling out an individual benefactor-beneficiary dyad for gratitude would be bizarre, under the circumstances. Given these expectations, the kind of aversive feelings associated with ingratitude would be blocked. In effect, the dāna ceremonies provide a basis for changing the expectations about expressions of gratitude. Schools in Thailand often organize group visits by children to participate and contribute to dāna ceremonies so that children can imbibe the expectations and values early on in life.

A primary function of gratitude is to maintain or strengthen a relationship with a thoughtful/considerate partner. Anumodanā fails to preserve this function insofar as gratitude is concerned with dyads at the individual level: self (beneficiary)-to-self (benefactor). But anumodanā preserves the function of maintaining and strengthening relationships at the group level: laity-to-monastic community. We’ve suggested that the additional benefits of gratitude—upstream reciprocity and moral reinforcement—are thus recovered. The monastic community acknowledges the benefit by expressing anumodanā and working harder to return the favour to the laity in the services they can offer, such as teaching, performing ceremonies, offering comfort, and so on. The laity offers dāna mostly to fulfil the material needs of the monastic community which allows for the preservation and perseverance of the saṅgha. This ensures upstream reciprocity since the services do not target an individual beneficiary but the Buddhist community as a group. The laity who joins in dāna ceremonies feel joyful on the occasion and are motivated to be more benevolent in the future. The benefits are endowed to the monastic community as representatives of the saṅgha and thus anumodanā also functions as a moral reinforcer.

F. Limits of Anumodanā Gratitude

Thus far, we have been celebrating the theoretical and practical innovations of Buddhism that allow for key functions of gratitude to be achieved without appealing to selves. However, there are important limits to how far these solutions extend. In particular, even if anumodanā and associated dāna ceremonies succeed in securing the function of gratitude in the relationship between the laity and the monastics, what about the relationships among the laity themselves? The mechanisms in place from the monasteries don’t obviously extend to the interpersonal case for the laity. A Buddhist parent might well feel quite wounded by the ingratitude of their son or daughter, and this is not likely to be assuaged by the kinds of practices associated with anumodanā. A recommendation to uproot interpersonal gratitude (kṛtajña) might be very costly. The Buddhists did not recommend getting rid of gratitude in partial relationships. Indeed, many sutras in the Nikāyas directly teach filial piety and regard it as an important virtue for the laity. For example, Aṅguttaranikāya (2.31−32) which is known in Pāli as the Kataññu Sutta (Kṛtajña sūtra in Sanskrit) notes that ingrate have no integrity. The sutra gratitude is explicated by the paradigm reciprocal relationship between parents and children.

Monks, one can never repay two persons, I declare. What two? Mother and father. Even if one should carry about his mother on one shoulder and his father on the other, and so doing should live a hundred years, . . . in supreme authority, in the absolute rule over this mighty earth abounding in the seven treasures,—not even this could he repay his parents. What is the cause for that? Monks, parents do much for their children: they bring them up, they nourish them, they introduce them to this world.

The Sūtra does not mean to suggest that one should not try to repay one’s parents because it is difficult to repay. Rather the Sutta goes on to explain how one can repay one’s parents.

But anyone who rouses his unbelieving mother and father, settles and establishes them in [Buddhist] conviction; rouses his unvirtuous mother and father, settles and establishes them in the Dhamma; . . . To this extent one pays and repays one's mother and father. (Thanissaro 2002).

This Sūtra shows that the Buddha recognised that the highest goal of enlightenment (nirvāna) and understanding and internalization of the radical no self view is going to be beyond what can be expected of every lay Buddhist and even novice monks and nuns.10 So, the Buddha laid a two-tier system with very different expectations from these groups, compared to the fully-ordained monastics. This is evident in the Buddhist sources which lists only five vows for the lay Buddhists, 10 for the novices, and over 200 for the monastics. It is worth noting that in the Pāli Vinaya, monastics are allowed to give the robe cloth or any other gift they have received to their parents. The special exception in the Vinaya rules makes it obvious that the Buddhists regard the parent-child relationship as a valuable one indeed.

In addition, the Buddha laid out numerous guidelines that pertain to the virtuous life for lay Buddhists. Being virtuous does not preclude the laity from enjoying the benefits to be had by indulging in partial relationships. Love and friendship are to be enjoyed by the laity while remaining on guard not to give in to infatuation, lust, and greed. The Sigalovada Sutta (DighaNikāya 31, Walshe 1995), which has been considered as the Vinaya [Buddhist code of discipline] of the householder, explains the ways to honour the six quarters that symbolize the different social relations of the householder: “The parents should be looked upon as the East, teachers as the South, wife and children as the West, friends and associates as the North, servants and employees as the Nadir, ascetics and Brahmans as the Zenith” (Thera 2010). These paradigm relations set out reciprocal duties and commitments so that the lay Buddhists are virtuous and social harmony is preserved in different interactions found in community life. Thus, for example, children owe respect and service to their parents and must therefore support them, fulfil their duties, keep the family tradition, make themselves worthy of their inheritance and honor the passing of the departed relatives by giving alms. Parents, on the other hand, must keep their children away from evil, show them the virtuous path, teach them labor skills, arrange for a proper marriage and grant them access to the family inheritance (Subasinha 1997, 28−31).

By having a two-tier system of vows and practices the living Buddhist traditions have been able to achieve what the free will skeptics aspire to. The Buddhist recognize the limits of anumodanā, so they supplement it by rejecting ingratitude as a vice especially in the context of partial relationships, paradigmatically that between parents and children. This is made clear in the Sīlavanāga Jātaka tale, the ingrate person is considered to be worst than a lowly animal. The Jātaka tales play an important role in communicating and educating that laity about the Buddhist virtues through the Bodhisattva stories.

V. Conclusion

Buddhism counsels a metaphysical revolution. Suffering is based on the false presupposition of a self, and the Buddhist says that we must uproot that false presupposition which will have the effect of reducing suffering. In this paper we have examined some potential costs of uprooting the belief in self. Reactive attitudes like gratitude seem to play a key role in a good life. A key function of gratitude is to strengthen and sustain personal relationships. Gratitude has several other beneficial consequences—it increases generosity, it reinforces moral behavior, and it enhances wellbeing. Yet gratitude seems to depend critically on the view that there are selves. In particular, gratitude seems to involve one self (the beneficiary) showing generosity towards another self (the benefactor).

We argue that Buddhists have a sophisticated response to this concern. First, some forms of gratitude do not involve the presupposition of self. One can be grateful for a beautiful sunset or the majesty of the mountains. But it’s also true that in everyday life, we feel grateful to particular people who benefit us. This kind of gratitude is harder to square with the no self view. Does that mean that we need to give up on this kind of gratitude altogether? Buddhists have both theoretical and practical innovations to address this. First, they introduce another notion of gratitude, anumodanā, which involves feeling joy (rather than directed gratitude) in response to the good deeds by another. Second, they implement a practice of celebrating generosity that does not involve appealing to the self. This is most clearly seen in the context of donations to the monastery. Buddhist communities organize elaborate dāna (gift-giving) ceremonies as public events encouraging everyone to participate in the joy of donating to the monastics to emphasize that gratitude (anumodanā) strengthens the symbiotic relationship between the monastic community and the laity, rather than a self-to-self relationship. Importantly, this kind of ceremony changes expectations about the kind of response to expect from being generous. As a result, a donor will not find the lack of directed gratitude aversive—it will not appear to them as an instance of ingratitude.

Thus, Buddhists have an impressive coordinated response—involving theoretical and practical revisions—to ensuring that important functions of gratitude are preserved. This set of revisions is largely targeted at monastics interaction with each other and with the laity. But what about the laity themselves? If the Buddhist rejects self-to-self gratitude, does this mean that children should not be grateful to their parents? Intuitively that seems quite difficult to bear, and Buddhism does not advocate a revolution that extends this far. Rather, Buddhist positively promote gratitude between children and their parents. This might mean that the laity do not live fully in accordance with the right metaphysics, but there is a strong practical strand in Buddhist philosophy. Insofar as the elimination of child-parent gratitude would increase suffering, this provides a reason against pushing the Buddhist no self revolution into family life.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kevin Berryman, Jay Garfield, Derk Pereboom, and anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier draft.

References

-

Algoe, Sara B. 2012. “Find, Remind, and Bind: The Functions of Gratitude in Everyday Relationships.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 6 (6): 455–69.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x]

- Appleton, Naomi. 2010. Jātaka Stories in Theravāda Buddhism: Narrating the Bodhisattva Path. Surrey, England: Ashgate.

-

Bartlett, Monica Y., and David DeSteno. 2006. “Gratitude and Prosocial Behavior: Helping When It Costs You.” Psychological Science 17 (4): 319–25.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x]

-

Berryman, Kevin, Monima Chadha, and Shaun Nichols. 2023. “Vows Without a Self.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 1 (20) 1–20.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12950]

- Blustein, Jeffrey. 1982. Parents and Children: The Ethics of the Family. New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Carlson, Elizabeth A. 1998. “A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Attachment Disorganization/Disorientation.” Child Development 69: 1107–28.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1132365]

-

Chadha, Monima. 2021. “Eliminating Selves and Persons.” Journal of the American Philosophy Association 7 (3): 273–94.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/apa.2020.27]

-

Chadha, Monima, and Shaun Nichols. 2022. “Self-Control without a Self.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00048402.2022.2049833]

-

Chadha, Monima, and Shaun Nichols. 2023. “Eliminating Selves, Reducing Persons.” In Reasons and Empty Persons: Mind, Metaphysics and Morality, edited by Christian Coseru. Sophia Studies in Cross-Cultural Philosophy of Traditions and Cultures. New York: Springer.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13995-6_6]

-

Cheng, Sheung-Tak, Pui Ki Tsui, and John H. M. Lam. 2015. “Improving Mental Health in Health Care Practitioners: Randomized Controlled Trial of a Gratitude Intervention.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 83 (1): 177–86.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037895]

- Cunningham, Clark. 2017. "Thot Kathin: The Ceremonial Presentation of New Robes and Gifts to Buddhist Monks in Thailand." University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Spurlock Museum of World Cultures Blog. Accessed Jan 23, 2023. https://www.spurlock.illinois.edu/blog/p/thot-katin-the/79, .

-

Dufwenberg, Martin, Simon Gächter, and Heike Hennig-Schmidt. 2011. “The Framing of Games and the Psychology of Play.” Games and Economic Behavior 73 (2): 459–78.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2011.02.003]

-

Elfers, John, and Patty Hlava. 2016. “The Lived Experience of Gratitude.” In The Spectrum of Gratitude Experience, 31–47. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41030-2_3]

- Emmons, Robert A., et al. 2019. “Gratitude.” Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures, edited by Matthew W. Gallagher and Shane J. Lopez, 317–32. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Accessed Jan 23, 2023. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1chrsd4.24, .

-

Emmons, Robert A., and Michael E. McCullough. 2003. “Counting Blessings Versus Burdens: An Experimental Investigation of Gratitude and Subjective Well-Being in Daily Life.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 377–89.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.377]

- Fillozat, Jean. 1991. Religion, Philosophy, Yoga. Delhi: Motilal BanarasiDass.

-

Froh, Jeffery J., William J. Sefick, and Robert A. Emmons. 2008. “Counting Blessings in Early Adolescents: An Experimental Study of Gratitude and Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of School Psychology 46: 213−33.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005]

-

Heim, Maria. 2004. Theories of the Gift in South Asia: Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain Reflections on Dāna. New York: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203502266]

- Horner, I. B. 1938–66. Vol. 4 of The Book of the Discipline (Vinaya-Pitaka). London: Pali Text Society.

-

Hume, David. (1739) 1969. A Treatise of Human Nature. Translated by Ernest Campbell Mossner. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/oseo/instance.00046221]

-

Israel-Cohen, Yael, et al. 2014. “Gratitude and PTSD Symptoms Among Israeli Youth Exposed to Missile Attacks: Examining the Mediation of Positive and Negative Affect and Life Satisfaction.” Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–8.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.927910]

- Kariyawasam, A. G. S. 1996. “5. Almsgiving and Funerals.” In Buddhist Ceremonies and Rituals of Sri Lanka. Access to Insight: Readings in Theravāda Buddhism. Accessed Feb 5, 2023. https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/kariyawasam/wheel402.html#ch5, .

- Keltner, Dacher, and Jennifer S. Lerner. 2010. “Emotion.” In Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by Susan T. Fiske, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Gardner Lindzey, 312–47. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

- Manela, Tony. 2021. “Gratitude” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta. Accessed Feb 3, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/gratitude/

-

McCullough, Michael E., et al. 2001. “Is Gratitude a Moral Affect?” Psychological Bulletin 127 (2): 249–66.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.127.2.249]

- Nanamoli, Bhikkhu, and Bhikkhu Bodhi. 1995. The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publication.

-

Nowak, Martin A., and Sébastien Roch. 2007. “Upstream Reciprocity and the Evolution of Gratitude.” Proceedings: Biological Sciences 274 (1610): 605–9.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.0125]

-

Otto, Amy K., et al. 2016. “Effects of a Randomized Gratitude Intervention on Death-Related Fear of Recurrence in Breast Cancer Survivors.” Health Psychology 35 (12): 1320–28.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000400]

-

Pereboom, Derk. 2001 Living without Free Will. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511498824]

- Pereboom, Derk. 2007. “Hard Incompatibilism and Response to Fischer, Kane, and Vargas.” In Four Views on Free Will, edited by J. Fischer et al. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

-

Siderits, Mark. 2008. “Paleo-Compatibilism and Buddhist Reductionism.” Sophia 47 (1): 29–42.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11841-008-0043-x]

-

Siderits, Mark. 2019. “Persons and Selves in Buddhist Philosophy.” In Persons: A History, edited by Antonia LoLordo, 301–25. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190634384.003.0012]

-

Sommers, Tamler. 2007. “The Objective Attitude.” Philosophical Quarterly 57 (228): 1–21.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9213.2007.487.x]

-

Strawson, Peter F. (1962) 2008. “Freedom and Resentment.” In Free Will and Reactive Attitudes: Perspectives on P.F. Strawson's “Freedom and Resentment,” edited by M. McKenna and P. Russell. Burlington, VT; Farnham, England: Ashgate.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203882566]

- Subasinha, D. J. 1997. Buddhist Rules for the Laity. Delhi: Pilgrim Books.

-

Suls, Jerry, Susan Witenberg, and Daniel Gutkin. 1981. “Evaluating Reciprocal and Non-Reciprocal Pro-Social Behavior—Developmental Changes.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 7: 25−31.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/014616728171005]

-

Swinburne, Richard. 1989. Responsibility and Atonement. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/0198248490.001.0001]

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu. 2002. "Kataññu Suttas: Gratitude." Access to Insight: Readings in Theravāda Buddhism. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an02/an02.031.than.html, .

- Thera, Narada. “Sigalovada Sutta.” In The Discourse to Sigala. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/dn.31, .

- Thera, Narada. 1960. “Everyman’s Ethics.” Four Discourses of the Buddha. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society.

-

Trivers, Robert L. 1971. “The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism.” Quarterly Review of Biology 46: 35–57.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/406755]

- Waller, Bruce. 1990. Freedom without Responsibility. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press

- Walshe, Maurice. 1995. The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya. Somerville: Wisdom Publications.

- Williams, Paul. 1998. Altruism and Reality: Studies in the Philosophy of the Bodhicaryāvata. Curzon Critical Studies in Buddhism. Richmond, Surrey: England Press.

-

Wood, Alex M., et al. 2009. “Gratitude Influences Sleep through the Mechanism of Pre-sleep Cognitions.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 66: 43–8.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.002]