A Confucian-Inspired Perspective on East Asia’s Future: Examining Social Cohesion and Meritocracy

© Institute of Confucian Philosophy and Culture, 2024

Abstract

East Asia’s economy is leading the world into the new Asian century. While meritocratic practices in the educational and private sectors are often considered pivotal conditions for East Asia’s economic success, experts have pointed out that the path ahead requires new approaches to ensure social cohesion and stability, which depend on the quality of relations across social divides. These considerations raise multiple questions for philosophers: What forms of social meritocracy are necessary to sustain social cohesion? Moreover, how can the detrimental effects of meritocratic practices be contained? Is it possible to utilise some of the intellectual resources indigenous to East Asia to generate innovative solutions? This paper argues that the answers to these questions lie in the indigenous Confucian conceptual resources. Confucian ideas can inspire a more desirable societal ideal for the future of East Asia. In particular, the Confucian emphasis on cultivating reciprocal harmonious human relationships and others’ morality can guide new approaches to fostering social cohesion. As Confucian personal cultivation through harmonious relations is a process of social cohesion, these ideas inspire a) a multiple approach to policymaking that is not only grounded in economic redistribution, b) a richer understanding of societal progress, and c) a democratic approach to fostering social cohesion. Unlike Confucian meritocrats and scholars who defend the Confucian roots of East Asian forms of political and social meritocracy, this paper proves that Confucian conceptual resources can help formulate a societal vision that strengthens cohesion and mitigates the adverse effects of meritocratic practices.

Keywords:

Confucianism, East Asia, social cohesion, social relationships, social meritocracyI. Whither East Asia?

With a regional GDP rising two times faster than those of Europe and USA, today, East Asia is the fastest-growing region in the world.1 Most observers believe the so-called East Asian “Miracle” or “Renaissance” is pertinent only in regional terms and is not reducible to China’s economic boom (Birdsall 1993; Gill and Karhas 2007, 6, 47). Furthermore, since East Asian countries have different political systems, the causes of East Asian Renaissance are likely to be “cultural,” not political.2

Against this backdrop, East Asian countries’ shared meritocratic elements in the educational sector and work culture have gained significant attention. These meritocratic elements have been pivotal for regional growth for Zorigt Dashdorj, the executive director of the Mongolia Development Strategy Institute. East Asian countries share a form of “educational meritocracy” that rewards hard work and ensures that the best students enter the national civil service systems or land jobs in top national business enterprises (Dashdorj 2019). While Japan was the first country to develop this educational system, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan quickly adopted several elements of the Japanese model, while China implemented a similar model after its economic reform in the 1970s (Dashdorj 2019). For Dashdorj (2019), meritocracy also defines many aspects of East Asia’s working culture, such as companies’ internal promotion system. Political theorist Daniel A. Bell seems to agree with Dashdorj. In his view, China’s economic success partly depended on the meritocratic culture in the political and educational sectors. For Bell, guanxi (关系), personal connections, still matter in China but are tempered by meritocratic practises. The gaokao (高考), the Chinese national university entrance exam, is emblematic of the Chinese meritocratic tradition (Bell 2015, 87). It is “a steppingstone for political success” and it “limits the power of elite by limiting access to examination success” (Bell 2015, 87). Reflecting on the practices of successful family enterprises in East Asia, the former Dean of the College of Business at Nanyang Technological University, Hong Hai maintains that “[m]eritocracy plays the additional role of culling the best available talent to serve as employee managers, in much the same way that elites mandarins in ancient China were selected through competitive examinations and subsequent performance as officials” (2020, 25).

The impact of meritocratic ideologies on East Asia’s economic performance is difficult to estimate; East Asia is a diverse region, with notable cultural, economic, and social differences among its countries. However, several countries in the region appear to urgently need a new socio-political vision. Economic expansion and massive development projects have led to an unsustainable social structure, challenging social cohesion in many East Asian countries (Gill and Kharas 2007). Within-country inequalities, wage inequality between skilled and unskilled workers, inequalities in educational attainment, and unequal access to essential services are the most pressing issues undermining social cohesion (Gill and Kharas 2007, 30). Thus, if numerous East Asian countries share some trust in meritocratic practices, they also appear to have a common problem: they “are failing in the achievement of domestic integration.” This jeopardizes not only social cohesion but also the sustainability of East Asia’s impressive growth (Gill and Kharas 2007, 18, 30).

East Asia’s need for an alternative societal vision for the future opens a new normative space. For example, as I have said, some observers believe that meritocracy was pivotal for the regional economic renascence, but are meritocratic practices and policies detrimental to social cohesion? If so, does East Asia have the intellectual resources to create a new societal ideal to ensure social cohesion? Furthermore, assuming that some forms of meritocratic selections are necessary for the functioning of vital societal sectors, how can the damaging effects of meritocratic practices on social cohesion be prevented?

This paper encourages a reassessment of the social value of meritocratic practices and argues that Confucian indigenous conceptual resources are an apt critical inspirational source for reconceptualising a desirable societal ideal. While some meritocratic practices are necessary for any society to sustain its functioning, empirical considerations on the effects of meritocratic practices should make us sceptical of the positive social effects of meritocracy. Yet, Confucian emphasis on cultivating reciprocal human relationships and responsibilities for others’ personal growth inspires novel ways to contain the toxic effects of meritocratic practices in the contemporary era. Thus, some Confucian ideas may well support the promotion of the worthy and competent, but they also offer an ethical counterbalance to meritocratic and divisive social practices. The paper proposes three Confucian-inspired recommendations for overcoming the toxic effects of existing meritocratic practices in East Asia by focusing on the Confucian idea of human relationship as a goal (at national and international political levels) and reciprocity as a shared responsibility.

The paper proceeds as follows: through sociological and economic studies on social cohesion and meritocratic policies in modern Singapore, the next section illustrates that meritocratic practices can erode social cohesion in the long term. These conclusions question the social effects of meritocratic practices. Section three presents a Confucian view of social cohesion. The fourth section uses some of the Confucian insights discussed in the third section to present three Confucian-inspired recommendations for sustaining social cohesion at the policy-making level. The final section addresses crucial objections to the proposal outlined in this article.

II. Social Meritocracy’s Effects on Social Cohesion

While the meaning of social cohesion remains open to debate, scholars agree that trustworthy and reciprocal social relations are a core dimension of social cohesion. For instance, David Schiefer and Jolanda van der Noll have recently proposed to view a cohesive society as “characterized by close social relations, pronounced emotional connectedness to the social entity, and a strong orientation towards the common good” (2017, 592). Such a definition aligns with most academic and policy-oriented approaches to social cohesion. It is also consistent with Joseph Chan, Ho-Pong To, and Elaine Chan’s influential definition of social cohesion as “a state of affairs concerning both the vertical and horizontal interactions of society as characterized by a set of attitudes and norms that includes trust, a sense of belonging and the willingness to participate and help, as well as their behavioral manifestations” (2006, 290).

Social cohesion is usually associated with “social networks.” The latter is the quality and quantity of people’s social relations with their family, friends, associations, and other groups (Schiefer and van der Noll 2017, 586). Like the idea of “social capital” proposed by Political scientist Robert Putnam (2000), the concept of social networks indicates that central to social cohesion is not just the frequency of personal interactions but also the level of trust and reciprocity developed by individuals (Schiefer and van der Noll 2017, 586). In particular, social cohesion is evident when citizens “can trust, help, and cooperate with their fellow members of society” (Chan et al. 2006, 289).

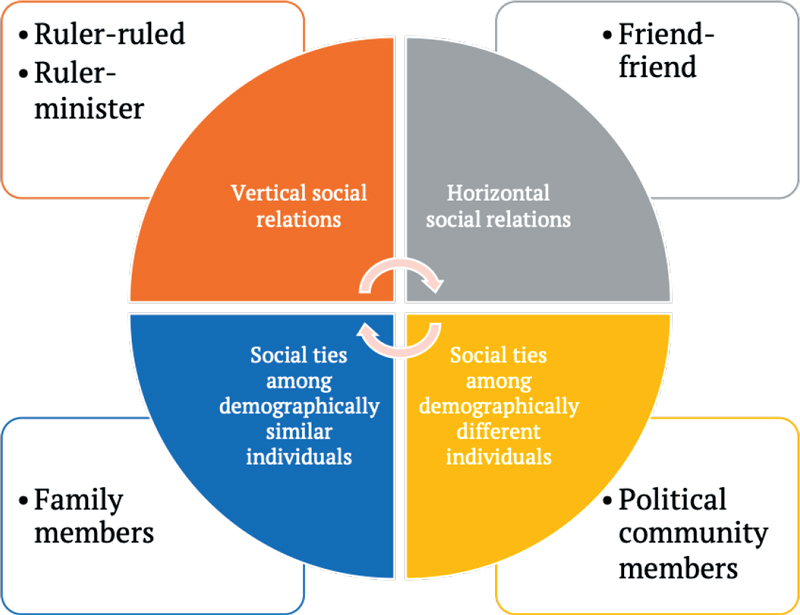

This indicates that for social cohesion to be present, both “bonding capital” and “bridging capital” are required. The former represents the quality of social relations among demographically similar individuals (e.g. work colleagues, family members, and neighbors). In contrast, “bridging capital” indicates the quality of social ties across social divides. Because social cohesion is a societal property, it depends on high bond capital and inter-group relations that allow for “bridging social capital” (Cheong et al. 2007). For this reason, relations across social divides and mutual tolerance between ethnic, cultural, and religious groups are often considered key indicators of social cohesion (Schiefer and van der Noll 2017).

Having clarified the meaning of social cohesion, let me turn to meritocracy. Meritocracy is a distributive principle that advocates allocating certain social goods to different members of society according to their desert under conditions of equality of opportunity (Mulligan 2018). For instance, in the case of job positions, meritocracy implies that positions should be open to all members of society and distributed according to candidates’ relevant qualities. As a distributive principle, meritocracy is not directly concerned with the quality of social relations among members of society. However, in real political scenarios, meritocracy has often been presented as a political ideal for fostering unity and cooperation across the social spectrum. For example, the first Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, believed meritocracy must be a core principle of modern and multiethnic independent Singapore. “[I]n a society based on equal opportunity, if rewards are corrected to the effort and output of the man and not to his possession of wealth or status, then is likely that you will give your people the incentive to strive for himself and for his community” (Lee 1966, my emphasis).

The development of meritocracy as a state ideology in modern Singapore is important for our discussion because it illustrates that meritocratic practices can erode social cohesion in the long term. After Singapore’s split from Malaysia in 1965, meritocracy represented the most suitable ideology around which Singaporeans could find common ground and trust in the institutions and fellow citizens despite their ethnic and religious differences. In a time of economic hardship and racial riots, Lee was persuaded that “[a] society based on performance, not pedigrees, has resulted in the benefit to all” (Lee 1980) and arguably, in the first decades after independence, multicultural meritocracy allowed for expanding social networks—an essential aspect of social relations. For instance, in the educational and private sectors, meritocratic selections were open to all Singaporeans regardless of their backgrounds and ethnicity. This allowed for more exchanges and the development of shared experiences between members of different ethnic groups, which had lived in segregated community ghettos during British colonial rule.

However, after six decades, meritocratic policies and ideology have led to worrisome class stratification and detrimental effects on Singapore’s social cohesion. According to Singaporean sociologist Vincent Chua and Singaporean economist Kelvin Seah, this is due to the fact that meritocratic competition in real-world situations never starts in perfectly equal situations. Furthermore, meritocracy can often lead to an advantage for a specific group that tries to pass their privilege to their children, thus ossifying the social structure (Chua and Seah 2022, 174). This shows that meritocratic systems tend in the long term to have the undesired effect of fostering class stratification, not social mobility. This long-term effect of meritocratic practices in modern Singapore was confirmed by Singapore’s Senior Minister and Coordinating Minister for Social Policies, Tharman Shanmugaratnam: “The top tends to preserve its ability to succeed in meritocracy, and the bottom tends to get stuck at the bottom end of the ladder. It is happening in many societies, and we are beginning to see it happen here” (Teng 2019, quoted by Chua and Seah 2022, 174).

Social cohesion studies confirm the long-term detrimental effects of meritocratic practices on social cohesion. According to Schiefer and van der Noll, equal resources contribute to levelling the playing field and increase individuals’ perception of fairness and trust in the system and in each other.3 “When individuals and groups have equal access to resources, this will strengthen their trust in others and institutions, enable them to participate and network, and facilitate a positive sense of belonging. This, in turn, contributes to their well-being and health, increasing their general quality of life” (2017, 594). In contrast, inequality of resources can lead to inequality of access, which places members of society at different starting points in the meritocratic race. These dynamics can erode social cohesion because they increase the perceived unfairness of the institutions and distrust among social groups.

Importantly, it is not just the perceived unfairness of the meritocratic selection to be problematic but also its spatial effects on social interaction. A meritocratic distribution of rewards can induce diminishing social interactions beyond the demographically similar. It induces individuals to adopt different lifestyles, reducing the chances of inter-group engagement between the “winner” and the “loser” of the meritocratic race. As a result, meritocratic practices decrease the chances for physical and social interactions and meaningful exchanges among different social groups in the long term. Such an effect is problematic: social cohesion tracks social relations based on trust and willingness to help each other and sharp inequalities can diminish social relations across the social spectrum.

Unsurprisingly, it is not just meritocracy that is being contested in Singapore; inequalities have also become a critical topic of debate. While meritocratic principles in the educational sector generated social mobility after independence, today’s education system has lost part of its potential. The problem lies primarily in families’ inequalities of wealth which intensify educational inequalities (Seah 2019). An area that clearly reveals the impact of inequality of wealth is access to private tuition. In the competitive Singaporean educational system, tuition has become necessary for many students to score decent grades at the elementary and secondary levels. However, in 2017/2018, the top 20 percent of Singapore households spent almost four times more than the lowest 20 percent of Singapore households on tuition (Chua and Seah 2022, 175).4

The history of meritocracy in Singapore is a cautionary tale for other East Asian countries and Confucian political theorists who advocate social meritocracy. While meritocratic practices are partly unavoidable in critical social sectors, they can also hinder social cohesion in the long term. However, note that the above discussion does not support the conclusion that meritocratic practices must be opposed under any circumstances; and there are reasons to doubt that a harmonious society can be achieved without some form of meritocracy. But the above empirical evidence must make us concerned about the social impact of meritocratic practices. Faced with this empirical evidence, we should doubt the potential of meritocracy as a means of social cohesion. At the same time, if some meritocratic practices are unavoidable, we must look for “counterbalances” to limit meritocracy’s corrosive social effects and nourish social relations. The following two sections turn to Confucian ideas for a possible solution to this problem: they show that some Confucian ideals can be an essential inspirational source for deliberation on the daunting lack of social cohesion and social meritocratic practices’ corrosive effects.

III. A Confucian View of Social Cohesion

Extending over a period of more than two millennia, Confucianism is one of East Asia’s most ancient intellectual traditions; it originated in China and progressively extended through East Asia and beyond its borders, maintaining its influence until the present day. Despite its internal diversity, Confucianism’s history is often divided into three main eras (Tu 1993). The first era is the ancient period, starting with Confucius (trad. 551–479 BCE) and ending with the Han dynasty's end (220). The second era expands from the Song (960–1279) to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Modern Confucianism characterizes the third and last period; it starts with the events of the May Fourth movement in 1919 and comprises the works of twentieth-century Confucian scholars, like Liang Shuming (1893–1988) and Mou Zongsan (1909–1995).

This intellectual tradition’s complexity makes it impossible to posit a singular Confucian perspective of social cohesion. As Confucian doctrines are various, so can the Confucian perspectives on social cohesion. Drawing from some of the central ideas of three fundamental ancient Confucian texts (the Analects of Confucius, the Mencius, and the Xunzi), I will argue that social cohesion can be understood as a key element of the political ideals proposed by the ancient Confucian masters.

In Confucian ethics, moral cultivation is an individual’s life goal achievable through developing certain moral dispositions or virtues. These virtues characterize the junzi (君子)—the noble person in the ethical sense of the term representing the Confucian paradigm of moral excellence—but every individual is born with equal potential to develop morally, regardless of background and social status (Analects 9.13).5

However, moral development is not an individualistic project in Confucianism, but a social one. This is because it depends on the possibility of establishing personal relations across space and time (Tan 2012, 300). Distinctive of Confucianism is a particular relational conception of the person. Individuals are not seen as independent entities from their social relations and the roles they play in them, but their relations with others also partly constitute them. This entails that, for Confucians, it is by cultivating harmonious and reciprocal social relations of care that the individual can develop morally and emotionally (Hall and Ames 1999).

The attitude of caring for others has a moral connotation. It goes beyond the physical tutelage or protection of the other, implying a contribution to the cultivation of others’ morality. This idea is expressed in the Confucian virtue of ren (仁), often translated as “benevolence,” “goodness,” or “humanity.” Ren is reflected in the attitude of the person who is “waiting to realize himself, he helps others to realize themselves” (Analects 6.30). While ren has a rich moral connotation, its correct expression may require achieving goals that prima facie seem unconcerned with morality. For example, helping others meet their basic needs because such needs are a precondition for moral development (Analects 13.9).

Clearly, not all human relations should be maintained if the other side does not reciprocate. Nevertheless, it is acceptable to the parties in the relationship to express ren according to their abilities and resources. For instance, because children are not self-sufficient, especially in the first years of their life, parents must provide more care for them than young children can reciprocate for their parents. Having said that, individuals with limited resources and a lack of moral authority have no excuse for passivity. Confucius expected his students to actively contribute to the educational process (Analects 7.8) and encouraged children to respectfully remonstrate (jian 諫) with their parents (Analects 4.18).

The emphasis on social relations reveals that cultivating harmonious human relations is an essential goal in Confucian ethics. Harmony (he 和), or “harmonization” (Li 2006, 583), is an individual goal for which the noble person should aim (Analects 13.23). At the same time, harmony is intrinsically a societal goal, it can be created and fostered by developing proper social relations with other individuals and nature. Importantly, for Confucians, harmony is not equal to uniformity; it represents a fruitful balance of differences (Analects 13.23). Modelled after the example of music, harmony presupposes diversity, requiring the mediation between individuals with different needs and different viewpoints (Li 2008, 425).

While traditionally, in Confucianism, the family represents the central social actor in the development of most individuals, the process of moral cultivation extends beyond the limits of families or small societal groups. Importantly, care for others’ personal development can be expressed in creating and nurturing relations among people of similar demographics across society and among members of society with different outward characteristics. Notably, the traditional five basic human relationships (wulun 五倫) (ruler-ruled, father-son, husband-wife, elder-younger, friend-friend) described in the Mencius (3A.4) and The Doctrine of the Means (20.8) include individuals with similar demographic characteristics (e.g. fatherson) but also individuals with radically different social positions and background (e.g. ruler-ruled). The affection that rulers should develop and express towards their people is a common theme in the ancient texts. Friendship can also develop among individuals with similar demographic characteristics, and numerous passages refer to the value of friendship relationships in the ancient texts. For instance, in the Analects, friendship is represented as essential to the noble person's life (12.24), and friendship with geographically distant others is one of the central topics of the opening passage of the Analects (1.1).

The importance of conducive vertical and horizontal social relations for individuals’ moral cultivation is clearly expressed in the Xunzi. For this Warring-States-period thinker, human flourishing does not only depend on the possibility of creating community (qun 㗔), but also on the presence of a socio-political order in which social roles are clearly defined (ch. 4, 294–306) and social relations are mediated through ritualized practices (ch. 9, 79–83). For Xunzi, rituals (li 禮) are a precondition for creating and sustaining harmonious relations in society because they have the potential to promote social order and cultivate individuals’ correct moral and emotional inclinations.6 To this end, Confucian rituals should encompass multiple spheres of societal life and public events, from funeral arrangements (ch. 19, 221–50) to statecraft (ch. 15, 98–101).

The above discussion suggests that Confucian personal cultivation through harmonious relations is a process of social cohesion. For the early Confucians, the ideal society is characterized by a network of strong social relationships among its members in which ritualistic practices help foster and maintain unity among members of society. From this perspective, the development of harmonious and ritual-based social relationships is not only a means to personal cultivation but also part of a broader process of developing a virtuous and cohesive society.

Of course, contemporary readings of social cohesion do not share the thick moral connotation that ancient Confucians ascribe to meaningful social relations. In other words, contemporary social cohesion experts do not consider ren or rituals. Nevertheless, the above discussion seems to indicate that a Confucian approach supports developing complex social networks quite similar to those necessary for social cohesion, as we understand it today. This is because it considers personal cultivation dependent on the quality of one’s social relations. Furthermore, it supports the development of vertical and horizontal networks of social relations, interpersonal trust, and a disposition for cooperation (see Figure 2 for a summary of the social networks supported by a Confucian approach).

This is a crucial point to make: it indicates that Confucian ideals can be an essential inspirational source for deliberation on the daunting lack of social cohesion in many East Asian countries. With their focus on high-quality social relations, some Confucian ideas can even bring a fresh perspective to debates on social meritocracy and inspire new ideas on how to foster social cohesion in East Asia. A Confucian insight on countermeasures is relevant beyond the debates among Confucians because, as we have learned, the social effects of meritocratic practices are also crucial for scholars involved in the discussion of the future of East Asia to determine what societal ideal can guide the new phase of regional development. The following section uses some of the Confucian insights discussed in this section to formulate three recommendations for constructing a sustainable societal vision to strengthen social cohesion.

IV. Confucian-Inspired Suggestions for Social Cohesion

This section argues that among the Confucian insights discussed in Section III, three are particularly useful: the Confucian idea of human relations as a goal at the local/national level; human relations at international political levels; and reciprocity as a shared responsibility.

A. Human Relations as a Goal at the Local/National Level

The preceding section has illustrated the detrimental effects of meritocracy-driven inequalities. On the one hand, they can increase mistrust among social groups, and on the other, they can diminish the chances for social relations across the social spectrum. Often, a concern for fairness leads policymakers and advisers to recommend controlling the implementations of meritocratic principles by redistributing resources from the better off to the worse off. While this is an important proposal, a Confucian-inspired perspective also advises creating physical opportunities for societal encounters between individuals with different backgrounds to ensure they can meet and develop social ties. For Confucians, the ability of meritocratic practices to decrease the chances for physical and social interactions among different social groups needs to be prevented. Personal cultivation is facilitated by cultivating social relationships beyond the demographically similar. This was one of the key functions of Confucian ritualistic practices. To this end, the Confucian emphasis on social relations would encourage today’s experimentation in urban design and, perhaps, refashion the educational system to allow pupils to develop cross-social class friendships and experiences.

This approach underlines some of the initiatives by the Singapore government to reduce the geographical distance between social groups. For example, besides the Ethnic Integration Policy that distributes public flats according to the ethnic heritage of the citizens to ensure mixed neighborhoods, similar plans have been developed to ensure a mixed class in the regulation of apartment rental or purchase (Chua and Seah 2022, 176). Another noteworthy initiative is the plan to redesign the education streams to allow more social mixing in schools. The debate on the desirability of these specific policies in the Singaporean context remains open, with critics maintaining that these political choices are likely to raise new challenges.7 However, my point is that the focus on the social context of these proposals is aligned with a Confucian-inspired approach that looks at the physical possibilities for individuals to establish and maintain social relations in their community.

B. Human Relations as an International Goal

The second Confucian-inspired recommendation involves adopting a deep understanding of societal progress at the international level. Social progress is often tracked by global indexes, like the Freedom House’s Freedom Index or the United Nations Human Development Index, which rank countries based on their ability to meet specific goals. Implementing a Confucian-inspired approach would complement existing indexes with an assessment of the quality of social relations across society, which would help understand how individuals can develop emotionally and morally by engaging and nurturing caring relationships across society.

Among all the proposed indexes to assess countries, the Harmony Index (HI) is the one that comes closest to this idea. Daniel Bell and Yingchuan Mo proposed the HI in 2013 as the first attempt to track the quality of social relations with a Confucian-inspired approach. The HI was a reaction against the leading global indicators which, according to the authors, “all suffer from the same basic flaw: they ignore or downplay the significance of social relations for human well-being, as well as the moral dimension of social life” (2014, 802). Against this backdrop, the HI aims to evaluate countries based on a country’s harmonious social relations and propose a new paradigm. The index tracks four types of harmonious relations: the relationships in families, in society, among countries, and between humans and nature.

The HI is an exciting and novel experiment. However, it is based on unsuitable measurements. For instance, it assesses the quality of parent(s)-child(ren) relationships based on the suicide rate of the elderly and children. The UN Women’s data on the rate of domestic violence is the only measurement to estimate the quality of relationships with spouses. These criteria are unsuitable for assessing the quality of social relations because they only signal the intolerable toxicity of social relations. Another issue with HI is that the quality of relationships in society depends on the “Club and Association Index” among other criteria. That suggests that HI does not focus on the quality of relations across social divides (the so-called “bridging capital”) but only on relations among similar individuals (that is, “bonding capital”) (Foa and Tanner 2012, 10). This is problematic because we have learned that meritocratic practices tend to ossify society in social classes, limiting precisely cross-class interactions.

In conclusion, while the authors acknowledge that their proposal is limited by the “lack of relevant measurements” (Bell and Mo 2014, 13), the above discussion indicates that HI does not track the quality of social relations, and developing an index on the quality of social relations across societies may require the creation of new criteria or parameters from those already in use. The above discussion also shows that pre-existing world indexes need to be revised to assess the quality of social relations. For instance, from the outset, the need to track social relations across social divides may lead us to think that the HI should be based on parameters such as the Inter-group Cohesion Index. However, the latter is based on the number of acts of violence among religious, ethnic, or other social groups (Foa and Tanner 2012, 10). But clearly, the absence of social conflict is not proof of social cohesion nor of close inter-group social ties.

C. Reciprocity as a Sharing of Responsibilities

The previous two recommendations suggest ways for policymakers and global analysts to recalibrate their perspectives on socially desirable goals. This final section argues that the corrosive effects of meritocracy on social cohesion are a problem not only of governance but mitigating the detrimental effects of meritocracy is a community’s responsibility. To this end, a Confucian perspective encourages a democratic problem-solving approach.

As we have learned, a Confucian perspective suggests that the moral responsibility to nurture reciprocal social relations does not rest exclusively on the shoulders of the more powerful. Each relation member is invited to contribute according to her resources and abilities. This point suggests that cultivating harmonious inter-group social relations is not only the government’s responsibility but also the community members. To this end, rectifying meritocratic principles in the education sector calls not only for new policy strategies and visions of social progress. It also requires school directors, teachers, and parents, who are in a position to change the environment in which pupils grow, to ensure that the latter are exposed to a different set of values more centred on personal cultivation rather than academic achievement and competition. The adverse effects of meritocratic principles on individuals’ social relations call for a collective response, but it does not exclude the need for governmental actions. Without structural changes to pluralize the educational selection system, it would be irresponsible and naïve for parents and teachers not to adequately prepare their children to compete for the meritocratic selection. The government and other top political institutions must work to reduce the detrimental effects of meritocracy. However, at the same time, they should allow local community actors to participate actively in the process.

This suggests that, in front of societal challenges, a Confucian perspective can encourage a democratic approach to problem-solving. I use the term “democracy” not as a principle of political legitimacy but as a way of life based on a collective experience of living together. It indicates a civic society open to all, in which members can contribute to solving collective problems according to their experience and possibilities. In this social environment, the collective sets the application and limits of meritocratic practices. While John Dewey (1888) was the first to elaborate on this understanding of democracy in the pragmatist tradition, this idea of democracy was later reconceptualized in Western political philosophy by the so-called “relational democratic theorists” (Bohman 1999; Anderson 1999, 2009; Scheffler 2010; Kolodny 2014). As a way for societies to identify and resolve their collective problems, democracy entails that social change is not the responsibility of a few but all community members. However, for pragmatists, democratic politics is not reducible to majority rule nor excludes the relevance of accountable democratic institutions (Dewey 1988, 365). Rather, it must be a form of “social inquiry” through which intelligent decisions are made to identify and solve problems via open debates, “socially organized deliberation,” and implementing experimental scientific methods (Bohman 1999, 591, 593). It presupposes collaboration among individuals with different backgrounds through reflexive personal judgment and collective deliberation. As an anti-elitist approach, democracy does not imply a flat equal distribution of labor. It invites citizens and different social actors to engage in a collective communicative activity according to their abilities. Such division of labor is democratic if it enables open and free communication between the general public and the other parties, and addresses recurring cooperation challenges towards the development of social knowledge (Bohman 1999, 592).

While the ancient Confucian master never advocated democratic rule, several contemporary Confucian theorists have pointed out that this pragmatic understanding of democracy has striking similarities with Confucian political ideals (Hall and Ames 1999; Tan 2005 and 2010; Kim 2016 and 2018).8 From a Confucian perspective, the government is the bearer of the highest responsibility to curb the socially corrosive effects of a meritocracy. However, all community members are responsible by virtue of being part of the community. This individual responsibility descends from the idea that personal development requires the person to exercise ren. As Tan argues: “Just as becoming ren begins with oneself, learning and realizing the way requires personal participation in solving the common problems of the community. To realize the way rather than merely follow it, there must be democratic participation in social inquiry to solve the shared problems of the community” (2012, 301).

V. Objection: Is Confucianism the Solution or the Root Problem?

Some may doubt that Confucian ideas can be an inspirational source for limiting meritocracy’s effects on social cohesion in contemporary East Asia. In their view, Confucian values influenced East Asian cultural orientations for millennia. Furthermore, many scholars believe that Confucian ethics is the primary intellectual root source of East Asian contemporary meritocratic practices, and several contemporary Confucian scholars support meritocratic principles for contemporary East Asian societies.

These considerations raise an important challenge to the proposal defended in this paper: if contemporary meritocratic practices originated from Confucian values, will emphasising the importance of Confucian values exacerbate these problematic practices instead of helping find feasible solutions? This final section addresses this objection in two ways. First, it shows that the exegetic debate on whether Confucianism supports a meritocratic conception of justice is still open. Second, even if normative elements of ancient Confucianism have contributed to supporting and developing some meritocratic toxic social practices in East Asia, today Confucian sources can inspire recommendations for limiting contemporary toxic practices.

Inspired primarily by the Chinese classics Mencius and Xunzi, Joseph Chan (2012) has argued that Confucianism supports a distribution of social and economic goods based on individual merits, provided that each member of society has sufficient resources and priority is given to the badly off.9 Chan’s defence of social meritocracy is primarily based on exegetic and normative considerations. However, the main Confucian justifications for meritocratic practices in the private sector must be instrumental. If personal cultivation is valuable in itself, Confucian support for meritocratic practices ultimately depends on their ability to create the desired social order for communal relations. To use Kim’s words: “for all three giants of Confucianism, desert as natural talent, though important, is not something that has an inherent moral value” (2013, 997). Thus, “[d]esert is valuable only if it is consistent with the telos of the Kingly Way, namely, moral self-cultivation and fiduciary social relationships” (Kim 2013, 997).

Following Kim, it can be concluded that Confucian values do not unconditionally support the implementation of meritocratic principles in the social sectors; the consequences of these practices on society must be considered, and alternative remedies must be proposed if meritocratic principles fail to achieve their goals. Importantly, even if some Confucian scholars would disagree with Kim’s interpretation of Confucianism, there are good reasons to believe in the potential of Confucian sources to inspire recommendations for limiting contemporary toxic meritocratic practices. Confucianism is not reducible to one single and static set of values. On the contrary, Confucian values are dynamic entities that have changed according to endogenous and exogenous changes. This proves that even if certain normative elements in ancient Confucianism contributed to the development of some meritocratic social practices in East Asia in the past, Confucian intellectual sources today could still inspire recommendations for limiting contemporary toxic practices today.

Tu Wei-ming (1989) makes this point in regard to the debate on the supposed Confucian origin of East Asia’s industrialization. For Tu, both sides of the debate wrongly assumed that Confucian values are stable conceptual categories that remain immutable over time. In contrast, Tu argues that Confucian values (like any other set of values) are dynamic entities: because they are “embodied in concrete human beings who consciously respond to changing situations, they undergo a transformation which is often inadvertent but sometimes deliberate” (Tu 1989, 91−92). Thus, the possibility of different interpretations of Confucian ideas allows for the influence of Confucian values on industrialization processes in different historical periods to result in different social practices and norms.10 Tu’s conclusion applies to the problem of the supposed relationship between Confucianism and meritocratic social practices. Even if certain Confucian elements or interpretations may have contributed to the development of some meritocratic social practices in the past, Confucian sources can still inspire contemporary political theorists in the generation of recommendations for limiting contemporary toxic practices. The two options are not mutually exclusive.

VI. Conclusion

Confucian ideals can be an essential inspirational source for pondering on the worrisome lack of social cohesion and unsustainable inequalities in many East Asian countries. A Confucian emphasis on cultivating reciprocal human relationships supports an instrumental approach to meritocratic practices in society. While most Confucians view some meritocratic practices as necessary for any society, empirical considerations on the effects of meritocratic practices should make them sceptical of the positive social effects of meritocracy. To this end, Confucian intellectual resources can inspire novel ideas on containing the toxic effects of meritocratic practices in the contemporary era. They suggest a) a multiple approach to policymaking that is not only grounded in economic redistribution, b) a richer understanding of societal progress, and c) a democratic approach to controlling the adverse effects of meritocracy and fostering social cohesion.

These suggestions open a new debate on Confucianism and social meritocracy. The need for more social cohesion in many countries in Contemporary East Asia urges scholars to shift their attention to different questions. Instead of asking whether existing meritocratic practices in East Asian societies originated from Confucian ideals, a more pressing issue is whether Confucian insights can inspire a new societal vision for contemporary East Asian societies and limit the detrimental effects of meritocratic practices in educational and work culture. To the extent that some forms of meritocratic selection are required to ensure high-quality service and expertise in critical social sectors, can Confucian ideas offer an alternative societal ideal? This question does not imply that Confucianism is the only intellectual tradition able to fulfil this task. My attempt to use Confucian resources to create new normative paradigms for East Asian contemporary societies aims to stimulate an inter-philosophical dialogue. It stems from the belief that ancient and contemporary Confucian intellectual resources are among the many invaluable conceptual resources that can inspire conceptual innovation in contemporary times.

References

-

Anderson, Elizabeth. 1999. “What Is the Point of Equality?” Ethics 103 (9): 287−337.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/233897]

-

Anderson, Elizabeth. 2009. “Democracy: Instrumental vs. Non-Instrumental Value.” In Contemporary Debates in Political Philosophy, edited by Thomas Christiano and John Christman. Oxford: Blackwell: 213−27.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444310399.ch12]

- Angle, Stephen. 2012. Contemporary Confucian Political Philosophy: Toward Progressive Confucianism. Cambridge: Polity.

-

Angle, Stephen, and Michael Slote. 2013. Virtue Ethics and Confucianism. New York: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203522653]

-

Bai, Tongdong. 2008. “A Mencian Version of Limited Democracy.” Res Publica 14 (1): 19–34.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-008-9046-2]

-

Bai, Tongdong. 2013. “A Confucian Version of Hybrid Regime: How Does It Work, and Why Is It Superior?” In The East Asian Challenge for Democracy: Political Meritocracy in Comparative Perspective, edited by Daniel A. Bell and Chenyang Li, 55−87. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139814850.004]

-

Bai, Tongdong. 2019. Against Political Equality: The Confucian Case. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691195995.001.0001]

-

Bell, Daniel. 2006. Beyond Liberal Democracy: Political Thinking for an East Asian Context. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400827466]

-

Bell, Daniel. 2015. The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy. Princeton University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400865505]

-

Bell, Daniel, and Yingchuan Mo. 2014. “Harmony in the World 2013: The Ideal and the Reality.” Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-of-Life Measurement 118 (2): 797–818.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0439-z]

- Berger, Peter. 1986. The Capitalist Revolution: Fifty Propositions About Prosperity, Equality, and Liberty. New York: Basic.

-

Berger, Peter. 1988. “An East Asian Development Model?” In Search of an East Asian Developmental Model, edited by Peter Berger and Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao, 3–11. New Brunswick: Transaction.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003575719-2]

- Birdsall, Nancy, et al. 1993. The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

- Bloom, Irene, trans. 2009. Mencius, edited by Philip Ivanhoe. New York: Columbia University Press.

-

Bohman, James. 1999. “Democracy as Inquiry, Inquiry as Democratic: Pragmatism, Social Science, and the Cognitive Division of Labor.” American Journal of Political Science 43 (2): 590–607.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2991808]

-

Chan, Joseph, Ho-Pong To, and Elaine Chan. 2006. “Reconsidering Social Cohesion: Developing a Definition and Analytical Framework for Empirical Research.” Social Indicators Research 75 (2): 273–302.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-2118-1]

- Chan, Joseph. 2012. “Confucianism.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Religion and Social Justice, edited by Michael D. Palmer and Stanley M. Burgess. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing.

-

Chan, Joseph. 2013a. Confucian Perfectionism: A Political Philosophy for Modern Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691158617.001.0001]

-

Chan, Joseph. 2013b. “Political Meritocracy and Meritorious Rule: A Confucian Perspective.” In The East Asian Challenge for Democracy: Political Meritocracy in Comparative Perspective, edited by Daniel Bell and Chenyang Li, 31−54. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139814850.003]

-

Cheong, Pauline, et al. 2007. “Immigration, Social Cohesion and Social Capital: A Critical Review.” Critical Social Policy 27 (1): 24–49.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018307072206]

-

Chua, Beng Huat. 2017. Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore. Singapore: NUS Press.

[https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501713453]

-

Chua, Vincent, and Kelvin K. C. Seah. 2022. “From Meritocracy to Parentocracy, and Back.” In Education in the Asia-Pacific Region, edited by Rupert Maclean and Lorraine Pe Symaco, 169–86. Singapore: Springer.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9982-5_10]

- Dashdorj, Zorigt. 2019. “Educational Meritocracy and East Asia’s Development Miracle.” GIS Geopolitical Intelligence Services, March 27, 2019. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/east-asia-education-system/, .

- Dewey, John. 1988. The Public and Its Problems. In The Later Works, Vol. 2. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Flanagan, Owen. 2019. “Modern Times and Modern Rites.” Journal of Confucian Philosophy and Culture 32: 17–39.

-

Fan, Ruiping. 2013. “Confucian Meritocracy for Contemporary China.” In The East Asian Challenge for Democracy: Political Meritocracy in Comparative Perspective, edited by Daniel Bell and Chenyang Li, 87−115. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139814850.005]

- Foa, Roberto, and Jeffery Tanner. 2012. “Methodology of the Indices of Social Development.” ISD Working Paper Series 2012-04. International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam (ISS), The Hague.

-

Foust, Matthew, and Sor-hoon Tan. 2016. Feminist Encounters with Confucius. Leiden: Bill.

[https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004332119]

-

Gill, Indermit, and Homi Kharas. 2007. An East Asian Renaissance: Ideas for Economic Growth. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

[https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-6747-6]

- Hall, David, and Roger Ames. 1999. The Democracy of the Dead: Dewey, Confucius, and the Hope for Democracy in China. Chicago: Open Court.

-

Herr, Ranjoo Seodu. 2003. “Is Confucianism Compatible with Care Ethics? A Critique.” Philosophy East and West 53 (4): 471–89.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2003.0039]

-

Herr, Ranjoo Seodu. 2012. “Confucian Family for a Feminist Future.” Asian Philosophy 22 (4): 327–46.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09552367.2012.729323]

- Hong, Hai. 2020. The Rule of Culture Corporate and State Governance in China and East Asia. New York: Routledge.

-

Jiang, Qing. 2013. A Confucian Constitutional Order: How China’s Ancient Pass Can Shape its Political Future. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691154602.001.0001]

-

Kim, Sungmoon. 2013. “Confucianism and Acceptable Inequalities.” Philosophy and Social Criticism 39 (10): 983–1004.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453713507015]

-

Kim, Sungmoon. 2016. Public Reason Confucianism: Democratic Perfectionism and Constitutionalism in East Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316226865]

-

Kim, Sungmoon. 2018. Democracy After Virtue: Toward Pragmatic Confucian Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190671235.001.0001]

-

Kim, Sungmoon. 2022. Im Yunjidang. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009024068]

-

Kolodny, Niko. 2014. “Rule Over None II: Social Equality and the Justification of Democracy.” Philosophy and Public Affairs 42 (4): 287–336.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/papa.12037]

- Hutton, Eric. 2014. Xunzi. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lee, Kuan Yew. 1966. Text of speech delivered at the Special Conference of the Socialist International Congress, Goteborg’s Nation, Uppsala University, April 27, 1966. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Lee, Kuan Yew. 1980. Prime Minister’s May Day Message, 1980. Accessed January 13, 2023. http://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/lky19800501.pdf, .

-

Li, Chenyang. 2002. “Confucianism and Feminist Concerns: Overcoming the Confucian ‘Gender Complex.’” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 27 (2): 187–99.

[https://doi.org/10.1163/15406253-02702005]

-

Li, Chenyang. 2006. “The Confucian Ideal of Harmony.” Philosophy East & West 56 (4): 583–603.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2006.0055]

-

Li, Chenyang. 2008. “The Philosophy of Harmony in Classical Confucianism.” Philosophy Compass 3 (3): 423–35.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2008.00141.x]

- Loy, Hui Chieh. 2014. “Classical Confucianism as Virtue Ethics.” In The Handbook of Virtue Ethics, edited by Stan van Hooft. New York: Routledge.

- Macrotrends. 2022. “East Asia & Pacific GDP 1960-2023.” Accessed on January 13, 2023. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/EAS/east-asia-pacific/gdp-gross-domestic-product

-

Mulligan, Thomas. 2018. Justice and the Meritocratic State. New York: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315270005]

- Mulligan, Thomas. 2022. “How East Meets West: Justice and Consequences in Confucian Meritocracy.” Journal of Confucian Philosophy and Culture 37: 17–38

-

Murphy, Tim, and Ralph Weber. 2016. “Ideas of Justice and Reconstructions of Confucian Justice.” Asian Philosophy 26 (2): 99–118.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09552367.2016.1163772]

-

Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/358916.361990]

-

Schiefer, David, and Jolanda van der Noll. 2017. “The Essentials of Social Cohesion: A Literature Review.” Social Indicators Research 132 (2): 579–603.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1314-5]

- Scheffler, Samuel. 2015. “The Practice of Equality.” In Social Equality: On What It Means to Be Equal, edited by Carina Fourie, Fabian Schuppert, and Ivo Wallimann-Helmer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Seah, Kelvin. 2019. “Tuition Has Ballooned to a S$1.4b Industry in Singapore. Should We Be Concerned?” TODAY, September 12. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://www.todayonline.com/commentary/tuition-has-ballooned-s14b-industry-singapore-should-we-be-concerned, .

- Slingerland, Edward. 2003. Analects. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

-

Tan, Sor-hoon. 2003. Confucian Democracy: A Deweyan Reconstruction. SUNY Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/book4734]

-

Tan, Sor-hoon. 2009. “Beyond Elitism: A Community Ideal for a Modern East Asia.” Philosophy East & West 59 (4): 537–53.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.0.0080]

-

Tan, Sor-hoon. 2012. “Democracy in Confucianism.” Philosophy Compass 7 (5): 293–303.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2012.00481.x]

- Tan, Sor-hoon. 2015. “Justice and Social Change.” In Comparative Philosophy without Borders, edited by Arindam Chakrabarti and Ralph Weber. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

-

Tan, Sor-hoon. 2019. “AI and the Confucian Conception of the Human Person: Some Preliminary Reflections.” SMU Research Data Repository (RDR). Conference contribution.

[https://doi.org/10.25440/smu.16717291.v1]

- Teng, Amelia. 2019. “Tharman: Parenting Must Evolve with Education System.” The Straits Times, February 16. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/education/tharman-parenting-must-evolve-with-education-system, .

- Valutanu, Luciana Irina. 2012. “Confucius and Feminism.” Journal of Research in Gender Studies 1: 132–40.

-

Van Norden, Bryan. 2007. Virtue Ethics and Consequentialism in Early Chinese Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511497995]

- World Bank. 2022a. Europe GDP. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/country/US, .

- World Bank. 2022b. USA GDP. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=EU, .

-

Ziliotti, Elena. 2020. “An Epistemic Case for Confucian Democracy.” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2020.1838736]